By Eleni P. Austin

“To fall asleep I need white noise to distract me, otherwise I have to listen to me think/Otherwise I pace around, hold my breath and let it out, sit on the couch and think about how living’s just a promise that I made.”

That slice of confessional angst pops up on the opening cut from Better Oblivion Community Center.

BOCC is a quicksilver collaboration between Los Angeles-based wunderkind Phoebe Bridgers and Indie Folk/Rock demi-god, Conor Oberst. The pair became personally acquainted when Phoebe played at a secret showcase he hosted at the Bootleg Theatre in L.A. It was something of a dream come true for Phoebe, who had idolized Conor since early adolescence.

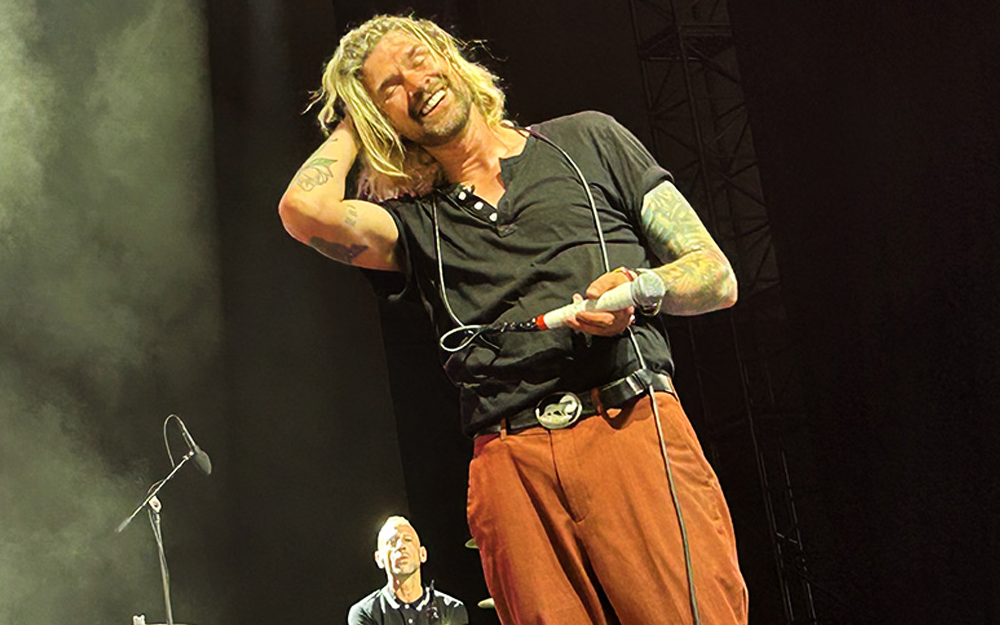

Conor Oberst was born in 1980 and grew up in Omaha, Nebraska, the youngest of three brothers. Music was an early obsession and by the time puberty hit, he was already hawking his own homemade, 4-track Cassettes. He made his bones in the tight-knit musical community of Omaha, releasing his first official solo recording in 1993, through what would become the influential indie label, Saddle Creek. Along with a couple of friends, he formed his first band, Commander Venus, after That came a brief detour in The Faint, followed by The Magentas and Park Avenue.

His most long-lasting and best-known band projects include Bright Eyes and Desaparecidos. Briefly, he formed a super-group, Monsters Of Folk, with Indie stalwarts, M.Ward, Jim James, and Mike Mogis. Throughout his career, Conor has distilled influences as disparate as the Cure, Bob Dylan, John Prine, Emmylou Harris, Daniel Johnston, Leonard Cohen, Elliott Smith and Neil Young, into a potent sound All his own. In turn, He has inspired countless younger musicians, including Phoebe Bridgers.

Like Conor, Phoebe’s musical ambition started at an early age. Born in 1994, Phoebe grew up in Los Angeles and was weened on a musical diet of Country, Classic Rock and Bluegrass. Although she didn’t stick with piano lessons, by adolescence she had begun playing guitar. One of the first songs she tackled was “Lovesick Blues” by Hank Williams, Sr. Once her mom enrolled Phoebe and her brother at Los Angeles High School For The Performing Arts, she got serious, taking Vocal Jazz classes. She still made time to busk on school grounds and started playing in the all-girl Punk band, Sloppy Jane.

Early influences included Tom Waits, Neil Young, Leonard Cohen, Joni Mitchell and Elliott Smith. She also felt an affinity to 21st century artists like Bon Iver, Blake Mills, Sun Kil Moon and, of course, Conor Oberst in all his permutations. An introduction to alt.country Rocker Ryan Adams led to some mentorship on his part. (In 2018, several younger female musicians, including Phoebe, levelled sexual harassment allegations at Adams, which he has denied). Inviting her to his studio, they recorded three songs in an afternoon and he released her first EP through his Pax Am label.

The EP created some buzz and Phoebe’s gigs got bigger and better. Pretty soon she was opening for musicians she admired like Julien Baker, the Violent Femmes and yes, Conor Oberst. Signing with the Dead Oceans label (home to Bleached, Destroyer and Slow Dive, to name a few), she connected with producer Tony Berg (Michael Penn, Edie Brickell, Squeeze, Aimee Mann, Replacements, X, Andrew Bird and Cracker) and recorded her long-playing debut, Stranger In The Alps, in late 2017.

The album was simultaneously intimate and expansive, featuring nine original songs and a devastating take on Mark Kozelek’s “You Missed My Heart.” The break-out single, “Smoke Signals” garnered airplay on taste-making L.A. radio stations like KCRW and KSCN. The album topped a lot of critics’ Top 10 lists. Her unique vision drove the album, but she received some superstar assists from Ethan Grushka, Greg Liesz, X front man John Doe and, you guessed it, Monsieur Oberst.

This new collaboration came about quite organically when both were recording (separately) in an L.A. studio. Phoebe and Christian Lee Hutson were stumped on what direction to take a song. Conor popped in (tripping on mushrooms) and made some surprisingly cogent suggestions. Rather surreptitiously, they decided to create an entire record together, which they completed in between other commitments. Under the completely anonymous sounding, weirdly self-helpy moniker Better Oblivion Community Center, their 10-song set popped up, taking the music industry by surprise.

The album opens tentatively with the aforementioned “Didn’t Know What I Was In For.” Wobbly acoustic guitar lattices Phoebe’s opening verse, as shadowy percussion stacks underneath. Conor joins in on the chorus as searing, e-bow adds some verdigris colors. Each verse feels like an emotional snapshot, capturing millennial ennui one minute and cognitive dissonance the next. The lyrics seem to hold a mirror up to these fractious times.

Rather than sing to each other, Conor and Phoebe sing with each other, completely eschewing any romantic component to this partnership. (Phew, given their 15 year age gap and Phoebe’s recent #metoo experiences, it would just feel icky). The pair settle in to a sonant camaraderie that hews closer to Simon & Garfunkel than Johnny & June.

Take the song “Service Road,” which feels like a barbed reflection on the sudden death of Conor’s older brother Matt. Dour acoustic strumming is leavened by twinkly percussion and tensile bass. His voice is suffused with confusion, anger and contrition as he attempts to unravel how it all went wrong; “Thought that he was doing better, a notice of final eviction and he just laughs/Always had a sense of humor, still joking till the bitter end, well all those threats he made can’t walk them back.” Phoebe swoops in on the carpe diem chorus; “Say what you mean and say it now, don’t throw a fit quit acting out/Who are you? Who are you waiting for?”

Although the arrangements here are mostly spare and acoustic, “Exception To The Rule” completely flips the script, fusing static-y synths and icy keys to a burbling beat. Even as opaque lyrics seem to advocate for delayed gratification the song time-travels back to an early ‘80s soundscape that would fit perfectly on a playlist that includes Human League and the Thompson Twins.

The best tracks here feel effortless. “Dylan Thomas” is breezy and economical, floating on a kick-drum beat, fuzz-crusted guitar, bouncing bass lines and slithery synths. Although the song’s title name-checks the 20th century poet and who died in 1953, the lyrics seem like a stinging indictment of the current political climate; “These cats are scared and feral with flag pins on their lapels, the truth is anybody’s guess/These talking heads keep saying the king is only playing four-dimensional chess.”

The vocals intertwine on the hushed and quiescent “Chesapeake.” Acoustic guitar notes lap over keening synths and pocket piano. The mood is melancholy and contrite, as cryptic lyrics unspool defining moments; “Even though no one’s around, you broke a leg and the house came down/A smattering of applause, a sliver moon and a cover song.” The melody hollows out drifting into the ether.

The Country Rock jangle of “My City” is powered by a tick-tock rhythm, chunky guitar riffs and Whirly Tube. A backhanded ode to the City Of Angels, the lyrics dart back and forth between the plague and pleasure; “This town is a monolith, this town is a crowded movie, this town is a depot, I come and go, this town is my city/I hate you, I tore you down I miss you, where are you now?” As momentum builds the whirring instrumentation matches the lyrics’ crushing emotional claustrophobia.

Finally, “Forrest Lawn” is a minor key charmer that offers a skewed trip down memory lane. The arrangement blends tilt-a-whirl acoustic guitars, pulsating percussion, and rock-ribbed bass over see-saw vocals. The opening couplet; “You used to sing with a straight face ‘Que Sera, Sera’ and drive those perfumed queens back to our place in a velvet box and then make your move” is wildly disarming. It sets the whimsical tone. Conor and Phoebe’s musical symbiosis is on full display in this tidy little waltz.

Other interesting tracks include the brittle “Big Black Heart” and the woozy drone of “Sleepwalkin”. The album closes with a version of Taylor Hollingsworth’s “Dominos” that veers from delicate to squally and back again.

BOCC relied on several friends to help their vision come to fruition, including bassists Wylie Gelber and Anna Butterss, drummers Griffin Goldsmith and Carla Azar and guitarists Christian Lee Hutson and Nick Zinner. Keys and synths were provided by John Congleton, Nathaniel Wolcott and producer Andy Lemaster.

It’s tough to predict if Better Oblivion Community Center will remain a one-off or become a full-time gig. Either way, Phoebe Bridgers and Conor Oberst have crafted a protean debut. For now, that’s enough.