By Eleni P. Austin

It’s always tempting to play “what if” when considering long-gone Rock musicians. What if Buddy Holly and Richie Valens hadn’t boarded that plane? What if Jimi Hendrix and John Bonham slept on their sides? What if Kurt Cobain had found a great Gastroenterologist? What if Big Star’s debut really had been a “#1 Record?” Would Chris Bell have still crashed his tiny Triumph sports car into a light pole and died instantly, at the tender age of 27?

Chris was born in Memphis, Tennessee in 1951. His British mother had met his American father during World War II. The fifth of six siblings, his dad owned a string of restaurants and Chris had a comfortable childhood focused on collecting comic Books. A life-changing event coincided with puberty; the Beatles debuted on Ed Sullivan in February, 1964. Instantly, Chris was hooked.

He quickly mastered the guitar and formed his first band The Jynx, (a tart tribute to British Invasion progenitors, the Kinks), in junior high. By high school he had made two important connections, first with teen singing sensation Alex Chilton, who fronted his own band before going nationwide as lead vocalist for the Box-Tops; then with John Fry, an avid audiophile who opened his own recording studio, Ardent.

In Chris, John Fry recognized a kindred spirit. His innate musical talent was astonishing. He also displayed a natural affinity for the recording studio. It wasn’t long before John gave Chris his own key to Ardent, allowing him, (and other well-chosen acolytes), free reign after hours. Chris made a half-hearted attempt to attend college, but he was consumed by music He quickly cycled through a series of bands, Rock City, the Wallabys and Icewater.

As the 60s gave way to the 70s, Alex Chilton returned to Memphis following the demise of the Box-Tops. He tried to enlist Chris into a Simon & Garfunkel-esque partnership, but Chris was already working with drummer Jody Stephens and bassist Andy Hummel. Intent on emulating his Fab Four idols, he convinced Alex to join his band.

Pooling the songs Chris and Alex created separately, and collaborating on a few more, they practically camped out in Ardent studio. Naming their band Big Star (after the local grocery chain that sustained them through lengthy recording sessions), they emerged in August 1972 with “#1 Record.”

“Brilliant” doesn’t adequately describe Big Star’s debut. It should have hit #1, but shoddy distribution meant the album only made it into the hands of a few influential music critics and some discerning record store clerks. Chris was devastated and actually snuck into Ardent intent on destroying the master recordings of “#1 Record.” After that he went home and swallowed a handful of pills in an apparent suicide attempt.

Although he had begun writing more songs for a follow-up album, he left them in Big Star’s custody and quit the band. They soldiered on as a three-piece, releasing the sunny Radio City in 1974 and the moody and quixotic Third in 1978. Both efforts were greeted with indifference from the record industry and the public, but the critics understood. In the next decade, Big Star would attain cult status, but that’s another story.

Quitting the band left Chris in emotional limbo for more than a year. Tentatively, he began to make music again, but he couldn’t return to Ardent, so he began recording at the tiny Shoe studio. With some help from old friends like drummer Richard Rosebrough and bassist Ken Woodley, he began laying down tracks.

Although he seemed inspired by the new songs, he remained deeply depressed. His recreational drug use had taken a harder turn. During a visit home, his brother David, (who had been living and working in Europe), was startled to find Chris injecting the opioid, Dilaudid.

Knowing his antipathy for needles, David realized Chris was in a bad place. He proposed a change of scenery, recommending they both return to Europe and check out the recording studios there. What began as an effort to re-ignite Chris’ passion for music became a two-year pilgrimage that took the brothers to Paris, London and Berlin.

They recorded at Chateau d’ Heroville, (where Elton John had made Honky Chateau and Goodbye Yellow Brick Road) as well as AIR studios in London. There they hooked up with producer/engineer Geoff Emerick, the man who engineered Beatles records like Revolver, Sgt. Pepper, the self-titled White album and Abbey Road.

When the Bell brothers returned to the States, Chris continued to work on the tracks at Ardent. They spent Christmas with their family and went back to Great Britain in early 1975. David shopped the songs to various labels and a couple showed interest, but Glitter and Glam were all the rage in the U.K. and no one seemed willing to market a singer-songwriter heavily influenced by the British Invasion.

Undeterred, Chris began gigging in small clubs in London and Berlin, he gained a following, but not enough of one to motivate a label to sign him. As the Bicentennial year dawned, he returned to America.

For the next couple of years, Chris continued to tinker with his music in fits and starts. Still prone to depression, he sought solace in spirituality, something he had begun to explore a few years earlier. His relationship to religion has been characterized as intense and complicated. There has always been speculation about his sexuality, maybe he felt immersing himself in religion was a way to combat feelings he didn’t want to acknowledge.

By 1978, he was still pursuing music, in fact, he had secured a deal to release a single “I Am The Cosmos” b/w “You And Your Sister” through Chris Stamey’s fledgling Car label. He was also managing a couple of his father’s fast food restaurants.

Meanwhile, in Europe there was a renewed interest in Big Star. Both #1 Record and Radio City were reissued as a double LP through the EMI label. Chris was delighted to see the back of the album imprinted with “EMI Records: Hayes, Middlesex, England, just like his beloved Beatles records.

Musically, things were looking up; he had begun writing songs with a local musician, Tommy Hoehn. Two days after Christmas, following a late-night session at Tommy’s apartment, Chris was driving home to his parents’ house. Somehow he lost control of his Triumph sports car and crashed into a light pole. He was killed instantly.

His funeral was held the following day, (ironically, on Alex Chilton’s 28th birthday). Per his sister Sara’s request, John Fry brought a copy of #1 Record to be buried with Chris. It felt like such an abrupt and tragic end to a promising career.

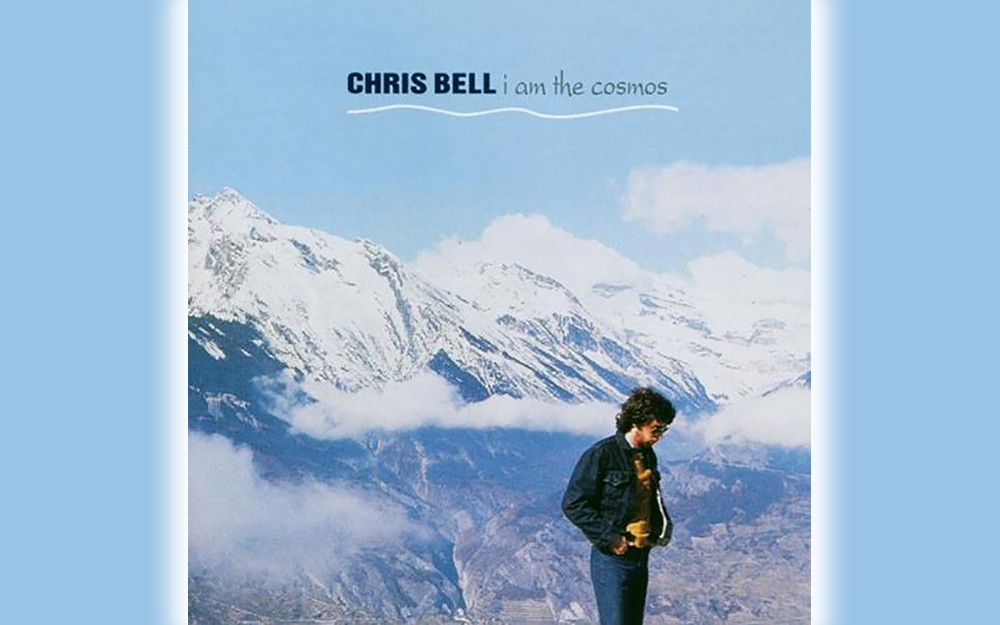

In the ensuing decade, as Big Star attained more than a cult following, and interest grew around the dozen solo tracks Chris had labored over the last years of his life. Finally, in 1992, the Rykodisc label released I Am The Cosmos. Since then, the 12 song set has been in and out of print. Now 25 years later, Omnivore Recordings has re-issued the definitive two CD set, gathering the original album, plus a bonus disc of demos and outtakes.

The album opens with the title track. Strummy acoustic guitar crests over this ragged mantra; “Every night I tell myself I am the cosmos, I am the wind,” Grinding bass and a handclap rhythm kicks into a dense, almost claustrophobic arrangement. His battered vocal delivery and searing guitar solo seem to mirror Chris’ insecurities and psychic pain.

Several songs crackle with authority, buoyed by crisp melodies and sharp instrumentation. They nearly manage to camouflage self-doubt and sadness contained in the lyrics.

Bitterness and betrayal are front and center on “Speed Of Sound.”

Couplets like “There’s a light in the darkness, it doesn’t seem far, is something the matter, the throttle’s ajar/The plane goes down, will not land, Pilot’s dead, nowhere to be found” weirdly foreshadow his own demise. But they’re irresistibly wrapped in gossamer guitar, honeyed harmonies, Moog synths and fingernail marimbas.

“You And Your Sister” could have been a hit on ‘70s AM Pop radio. Chris’ pure pop instincts would have easily sandwiched between bands like Bread and Firefall. Sparkly acoustic guitars ebb and flow, lapping over doubletracked vocals and a sylvan string section. Although her sister seems to have given Chris a bad rap, he quietly insists “All I want to do is spend some time with you, so I can hold you.”

The stuttery “Make The Scene” blends throbbing bass lines whooshing Moog runs, plenty of cowbell and an off-kilter beat. His gritty guitar work on the instrumental break displays a confidence that seems absent when he petulantly confronts an unfaithful lover; “You didn’t have to be so mean, You didn’t have to make a scene/You didn’t have to be so cruel, Make me feel like a fool.”

“I Don’t Know” juxtaposes lyrics that equivocate from one verse to the next, with a melody and arrangement that simply bristle with self-assurance. Rippling guitar riffs collide with rumbling bass and a pounding back-beat, off-setting indecisive declarations like “You don’t know what you’re putting me through, I gotta get away from you/Do you want me? I want you, You don’t want me, I want you.”

Three tracks echo the shambolic charm that characterized the best Big Star songs. On “Get Away,” pummeling drums ride roughshod over crunchy guitar, pulsating bass lines and tick-tock percussion. Here Chris confides “Whenever I feel like I’m sinking, you make it a beautiful scene.”

“I Got Kinda Lost” is an easy-going Rocker fueled by slippery guitar riffs, roiling bass and see-saw rhythms. For once, Chris lets the cosmic confusion wash over him, as a stinging guitar solo neatly blunts his continued amorous angst.

“Fight At The Table” opens tentatively with exploratory bass lines, soulful guitar licks and twinkly hi-hat percussion, only to be overtaken by playful Honky-Tonk piano notes, swooping synthesizers, wah-wah guitar and even a saxophone. Instead of his usual romantic sturm und drang, the lyrics are dotted with non-sequiturs; “I started dreaming ‘bout Emma, and he said ‘don’t interfere,’ said ‘whatcha doin’ in Denver? There’s no light in here.’”

Both “Better Save Yourself” and “There Was A Light,” focus on his serious flirtation with religion. The former is brooding and crepuscular. Droning keys, shuddery guitar and tumbling drums set the tone for this corrosive lullaby.

In between making a case for supplicating to a higher power; “You should’ve given your love to Jesus, it couldn’t do you no harm,” and castigating non-believers; “You’ve been sitting on your ass, trying to find some grace, but you better save yourself if you want to see his face,” Chris admits to trying to end it all, “It’s suicide, I know I tried it twice.” The tune is equal parts harrowing and heartbreaking.

The melody and instrumentation of the latter borders on beatific. Spare and elegant, the track is propelled by guitar, bass and mellotron. The lyrics offer an unequivocal paean to the power of Jesus; “Look up, look up, he’s the life waiting to love you, wanting to reach you.”

The desolate “There Was A Light” includes an aching guitar solo that almost ameliorates lyrics like “Spending all my time waiting to die, what’s the use?” The album closes with the poignant cri de couer of “Though I Know She Lies.” The sweet melody is accented by warm waves of electric piano, acoustic, electric, slide and steel guitars. Again, the shimmery instrumentation act as a palliative as it juts up against lyrics like “Lying in bed trying to cope with my feelings, I don’t know if it’s love but what can I do? I fall every time though I know she lies, I can’t stay away.”

Originally, that was where this sadly beautiful record concluded, but the kids at Omnivore have scoured the vaults, tacking on an astonishing 23 tracks, offering alternate and instrumental versions, demos and acoustic mixes. Some of this stuff is simply revelatory. There are also two collaborations featuring local Memphis musicians: “Stay With Me,” with Keith Sykes, “In My Darkest Hour” with Nancy Bryan, as well as “So Long Baby (a.k.a. “Clacton Rag”), written in 1976.

When Chris was killed, local Memphis newspapers referred to him as the “son of a local restauranteur.” It was as if the cosmos delivered a final blow. Family, friends and Big Star fans knew he was so much more. It’s taken decades for the rest of the world to catch on. I Am The Cosmos is suffused with blood, sweat and tears, sadness and joy, and most of all, undeniably beautiful music. Although he never attained the Rock N Roll stardom he richly deserved in life, he has become a touchstone for generations of musicians. It’s not quite enough, but it will have to do.