By Eleni P. Austin

In 1968, as John Lennon and Paul McCartney were holding a press conference to announce the formation of Apple Corps, a reporter asked John to name his favorite American musician. The response was “Nilsson.” When Paul was asked who his favorite band was, his answer was the same, “Nilsson.”

Harry Edward Nilsson III was born in New York in 1941, three years later, his father abandoned Harry and his mother. He grew up poor, in a railroad flat in Brooklyn, before his family moved to Los Angeles, in search of brighter financial opportunities. In order to help support his family, which eventually included younger half-siblings, Harry quit high school. Initially, he worked in a movie theatre and eventually at a bank. (He presented himself as a high school graduate, and although his deception was discovered, he remained employed, having displayed an aptitude for computers). It was around this time that he began plotting a career in music. At the outset, like Cher and later Prince and Madonna, he preferred the mononymous moniker, Nilsson.

Although the Nilsson family was poor, they were rich with musical talent. The advent of Rock N’ Roll, and Ray Charles in particular, really sparked Harry’s interest. He quickly learned guitar and piano, formed a short-lived duo with his friend Jerry Smith, and also began writing his own songs. In 1963, Little Richard recorded “Groovy Little Suzie,” co-written by Harry and John Marascalco. He signed with a couple of smaller labels, intent on recording his own songs. That didn’t get him very far, but he was beginning to build a reputation as a songwriter. Disparate artists like Fred Astaire, Glen Campbell, the Shangri-Las and the Yardbirds had recorded his songs. This led to a record deal with the RCA label in 1966.

A year later, his full-length debut, Pandemonium Shadow Show arrived. A mix of expansive originals and perspicacious covers, including a couple of Beatles deep tracks, it showcased Harry’s three-octave range. Commercially, it went absolutely nowhere. However, music critics were paying attention. So was Derek Taylor, the Beatles’ publicist actually bought an entire case of the record, giving them to friends, which included the Fab Four and savvy industry insiders. Soon the Monkees were covering the song “Cuddly Toy.” As a result Monkee vocalist/drummer, Micky Dolenz became a life-long friend.

His second effort, Aerial Ballet arrived in 1969 and featured “One,” a song constructed around a telephone busy signal, which Three Dog Night took to #5 on the Billboard Charts. It also included his version of Fred Neil’s “Everybody’s Talkin’,” which became the theme song for the film “Midnight Cowboy.” The song proved to be Harry’s commercial breakthrough, reaching #6 on the charts and winning a Grammy. He wound down the ‘60s writing the soundtrack for “Skidoo,” an Otto Preminger film, and releasing his third solo album, simply entitled Harry.

The 1970s would prove to be Harry Nilsson’s decade. It began with Nilsson Sings Newman an entire album devoted to the songs of Randy Newman, followed by The Point, a soundtrack to an animated children’s special that aired on ABC. His watershed album, Nilsson Schmilsson, arrived in late 1971, it marked his first collaboration with producer Richard Perry.

The record included three enormous hit singles. His soulful cover of the Badfinger track “Without You” went to number #1 in Australia, Ireland, the U.K. In the U.S. it hit #1 simultaneously on two charts, Rock and Pop. Harry practically invented the Power Ballad, creating an arrangement centered on strings, horns and his lachrymose vocals. The Tropically-tinged “Coconut,” was a goofy saga told by four different characters and was more thoroughly appreciated after some herbal refreshments. It made it to #8 on the Rock charts. Finally, “Jump In The Fire” was a flat-out Rocker that signaled a change of pace, and hit #27 on Billboard’s Hot 100. He even earned a Grammy for Best Male Pop Vocal Performance. Everybody, it seemed was talkin’ about Nilsson.

From there, Harry was simply en fuego, Son Of Schmilsson was released in the summer of ’72. Even though only eight months elapsed since his breakthrough, this was another assured collection of songs. His next record, A Little Touch Of Schmilsson In The Night took a hard right turn by covering standards like “You Made Me Love You,” “Always” and “As Time Goes By.” Although these days, this sort of career move has become de rigueur for Rock musicians, Harry was the first guy to take that risk.

By this time, Harry had become fully immersed in the Lifestyles Of The Rich & Famous Rock N’ Rollers. He had been befriended by all of the Beatles, but bonded most completely with John Lennon and Ringo Starr. He collaborated with the latter on the film “Son Of Dracula” and it’s concomitant soundtrack. After Yoko Ono kicked John out and he retreated to L.A., Harry became his boon companion in what John later described as his extended “lost weekend.” Officially, John was producing Harry’s 10th studio album, “Pussycats,” but mostly, the pair could be found out on the town, imbibing a smorgasbord of illicit substances and wreaking havoc with a who’s who of Rockers like Keith Moon, Jim Keltner, Klaus Voorman, Ringo and Jesse Ed Davis.

It was during this lengthy, sybaritic spree that Harry ruptured a vocal cord during a recording session, but hid the injury from John and continued singing. The record was a chaotic mess, although he wrote and recorded new music between 1975 and 1980, (Duit On Mon Dei, Sandman, …..That’s The Way It Is, Knilsson and Flash Harry) his commercial appeal greatly diminished as the decade wore on.

Following two failed marriages (the latter produced his eldest son, Zak), Harry found happiness the third time around with Una O’Keefe. The couple settled down and had six children together. In late 1980, he was dealt a brutal blow, when John Lennon, who had recently returned to making music, was shot dead in the street by an obsessive “fan.” Throughout the ‘80s, Harry’s musical output was sporadic. He began devoting his time to gun control issues and his musical ambitions took a back seat. In the early ‘90s he found out a duplicitous business manager had embezzled his fortune. After spending three years in prison, she was released without ever paying restitution.

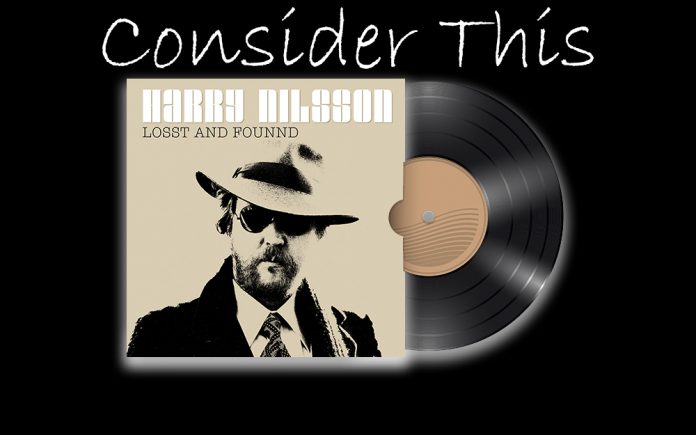

After he suffered a massive heart attack in 1993, Harry began to press the RCA label to release a retrospective box set. He also began diligently recording new songs with producer Mark Hudson. Tragically, he died from heart failure in early 1994. He was just 52 years old. The songs, some of which were brand new, while others dated back to the ‘70s and ‘80s, remained in limbo after his death. But Mark forged ahead, adding the musicians from Harry’s wish list throughout the years and essentially following Harry’s sonic blueprint. Now, thanks to the fine folks at Omnivore Recordings, collected these songs and they are finally seeing the light of day as Losst And Founnd. (See what they did there?)

The album opens with the title track. Written in the early ‘90s, the melody has a nursery rhyme quality that harkens back to his earliest children’s songs. However, the lyrics tackle grown-up topics. Jangly guitars are bookended by layers of bass, percussion, synths, piano, B3, more guitars and a horn section. Harry’s vocals are open and folksy, even as he mixes the personal with the political; “One for the government, two for the President, standing outside right next to his monument/How can take the problems from the innocent, one for the indigent standing on pavement.”

This collection is dotted with compositions originally written in the 1970s and 1980s, yet they don’t seem the least bit dated. Both “U.C.L.A.” and “Try” originally incubated in the ‘70s, but feel timeless. The former is typically tongue-in-cheek. The breezy melody and playful vocals are anchored by a see-saw rhythm, pliant piano, dobro and slide guitar accents, wiry bass lines, a wash of Hammond B3, plus horns, strings and percussion. Harry gets the ball rolling with a droll “yeah…” But things take a wistful turn as he trips down Mop-Top memory lane; “There is no place like Penny Lane, there’s no more yesterday, but something’s in the way you move me, keeps moving me from day to day.” A fluttery arrangement adds some Fab Four fripperies; a tart trumpet fanfare, lang syne strings, ascendant guitar notes, and a rumbly bass line that simply comes together, underscoring the nostalgia. The latter is a roguish shuffle that matches motivational “Hang-In-There-Baby” lyrics to Harry’s laconic delivery and blustery instrumentation.

The ‘80s tracks are represented by “Lullaby” and “Woman Oh Woman.” “Lullaby” blends silky strings, nimble bass, twinkly celeste and piano, hushed guitars and a tip-toe meter. The sleepy-time cinematic sweep is tied together by gentle lyrics that sooth a child’s bedtime jitters; “Your eyes are just as heavy as lead, there’s nothing left to be said, it’s time to call it a day, the sandman’s on his way, it’s time to say goodnight and reassure you/A pillow’s just a pillow, your army’s gone to bed, there’s nothing left to say but I love you.”

“Woman…” is a woozy paean to womankind that drafts off the old I-vi-IV-V progression of the Hoagy Carmichael chestnut, “Heart And Soul.” Bleating synths, tensile bass, plangent piano, and shimmery guitars connect with exotic bowljo notes, horns and a Parisian-flavored accordion, courtesy Van Dyke Parks. Harry’s admiration feels a touch patronizing, when viewed through the current “#metoo” prism; “If you knew true devotion, you’d jump into the ocean and drown, going down thinking of me.” But it’s clear his heart’s in the right place. There’s a bit of “Pet Sounds” heft on the break.

Harry slips in a couple of cover songs. “Snow” is a Yoko Ono track that originally appeared on John and Yoko’s third joint effort, “Wedding Album.” One of her more conventional efforts, it receives a lush, vaguely tropical arrangement here. Yoko’s reticence is replaced by Harry’s self-assured take. The album’s final song, “What Does A Woman See In A Man,” was written by Jimmy Webb, a ‘60s contemporary and equally lauded wunderkind songwriter. It began life as a sardonic piano ballad that landed somewhere between Tom Waits and Warren Zevon. In Harry’s hands, it receives a lush, rococo, classically inclined arrangement. Erudite lyrics pay homage to the enduring patience practiced by the fairer sex; “His stomach hangs out and there’s a hump on his back and he eats like Conan The Barbarian/While she keeps herself trim, and her posture is prim, and her manner is quite cosmopolitan…tell me, what does a woman see in a man?”

Other interesting tracks include the Orwellian Big Easy strut of “Animal Farm,” and the achingly sincere “Love Is The Answer.” There’s a sporty shout-out to L.A. baseball with “Dodger Blue” and the rollicking “Hi Heel Sneakers/Rescue Boy Medley.” Here, Harry cannily fuses the 12-bar Blues of the early ‘60s hit with one of his final compositions.

Harry Nilsson was something of a musical unicorn. He effortlessly blended genres like Baroque Pop, Psychedelia, Jazz and the American Songbook into a seamless aural tapestry. Although he was never fully appreciated in his own time, his influence is exponential. Everyone from The Turtles to Neko Case, the eels, Cypress Hill and Aimee Mann have covered his songs. He should have been inducted into the Rock & Roll Hall Of Fame when he first became eligible, decades ago, while he was still around to enjoy it. In any case, the time is right for a Nilsson Renaissance. Losst And Founnd is a gentle reminder of an epic talent.