Book Review by Heidi Simmons

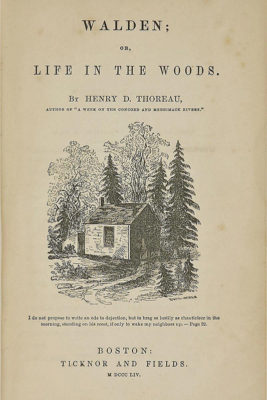

“I went to the woods because I wished to live deliberately, to front only the essential facts of life, and see if I could not learn what it had to teach, and not, when I came to die, discover that I had not lived. I did not wish to live what was not life, living is so dear; nor did I wish to practice resignation, unless it was quite necessary. I wanted to live deep and suck out all the marrow of life, to live so sturdily and Spartan-like as to put to rout all that was not life, to cut a broad swath and shave close, to drive life into a corner, and reduce it to its lowest terms, and, if it proved to be mean, why then to get the whole and genuine meanness of it, and publish its meanness to the world; or if it were sublime, to know it by experience, and be able to give a true account of it in my next excursion.” – Henry David Thoreau, Walden (Shambhala, 303 pages).

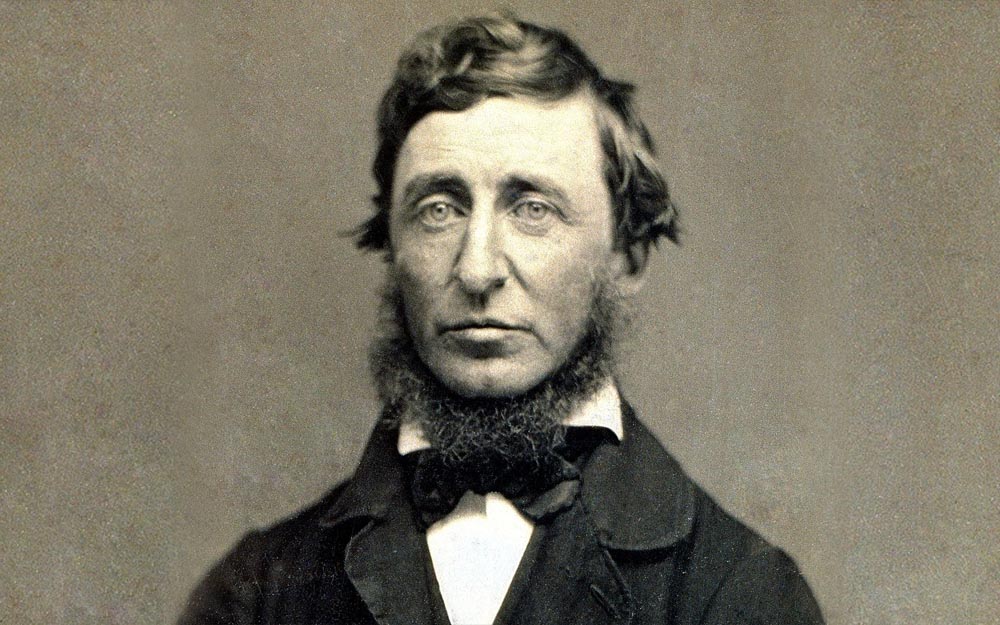

The author of these famous words turned 200-years-old this month. Thoreau’s most celebrated – Walden – work seems utterly relevent today.

At the age of 30, Thoreau wrote his greatest treatise after spending two years at Walden Pond in Concord, Massachusetts. He built a tiny cabin on the property of his contemporary and friend, Ralph Waldo Emerson, in search of a truth about life and existence.

An essayist, philosopher, poet, historian, anarchist, transcendentalist, Thoreau lived as passionately as he could recording his experiences to share and to analyze. He had an intense love for freedom and resentment toward the expanding Federal Government. So Thoreau looked to the elegance, wisdom and simplicity of nature for answers.

When Walden was first published, it was not popular. As odd as that may seem, it makes sense considering the era. The North was only beginning to outlaw slavery and Thoreau was a staunch abolitionist. The United States was engaged in the Spanish American War. A civil war was just a decade away. Industry exploited natural resources with abandon.

When Walden was first published, it was not popular. As odd as that may seem, it makes sense considering the era. The North was only beginning to outlaw slavery and Thoreau was a staunch abolitionist. The United States was engaged in the Spanish American War. A civil war was just a decade away. Industry exploited natural resources with abandon.

A year after Walden, Thoreau gave lectures about his experience. He then formulated a speech called, “The Rights and Duties of the Individual in Relation to Government.” This became an essay entitled Resistance to Civil Government (1849) which was then published as Civil Disobedience.

In the essay: “Thoreau argues that individuals should not permit governments to overrule or atrophy their consciences, and that citizens have a duty to avoid allowing such acquiescence to enable the government to make them the agents of injustice.”

Still topical?

Thoreau was Harvard educated, as was his pal Emerson. The two shared a belief in Transcendentalism – a philosophy that at its core believes in the inherent goodness of people and nature. Applied, transcendentalists view society and its institutions as having corrupted this purity, and believe people are at their best when they are independent, self-reliant and have the freedom of self-expression.

For me, “Transcendence” especially made sense for the time as states argued, using religiosity, to defend slavery. It seems to me, as a philosophy, it was a way to get people to think for themselves and to use reason and facts, rather than rely on political parties or the church to make important decision about individuals.

I cannot help but wonder what role Thoreau would play in our society now. But regardless of his political views or spiritual values, his work harkens to the individual’s heart and mind, and our desire to cope with, and understand our place in the universe, and our role on this planet.

“I only know myself as a human entity; the scene, so to speak, of thoughts and affections; and am sensible of a certain doubleness by which I can stand as remote from myself as from another. However intense my experience, I am conscious of the presence and criticism of a part of me, which, as it were, is not a part of me, but spectator, sharing no experience, but taking note of it; and that is no more I than it is you.”

Happy Birthday Mr. Thoreau!