By Heidi Simmons

—–

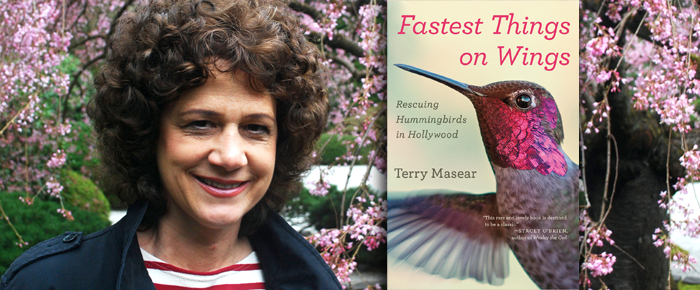

Fastest Things on Wings

by Terry Masear

Non-Fiction

——

Who isn’t awed by those little flying creatures that dart around our azure blue sky and hover while taking nectar from desert blossoms? Beyond their amazing flying skills, their magnificent colors dazzle our eyes with flashes of electric purple, luminescent magenta or neon tangerine.

Speed, beauty and intelligence are only a few things to discover about the amazing hummingbird in Terry Masear’s Fastest Things on Wings: Rescuing Hummingbirds in Hollywood (Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, 320 pages). What is most significant in this labor of love – both for the birds and the writing of the book — is the effect hummingbirds have on human beings.

Author Masear is a hummingbird rescuer and rehabilitator. She, her husband, several cats and nearly a hundred hummingbirds live in their West Hollywood home just blocks from the Pacific Design Center in the heart of the over-populated Los Angeles sprawl.

From April to August, Masear takes time off from her job as an English professor at UCLA to tend orphaned and injured hummingbirds. Whether the birds are brought to her home or she picks them up, each bird gets a name, attention and specialized care. Her singular objective is to release a healthy bird back into the wild.

Every season she receives over 2,000 calls about the little darlings. But being a hummingbird rescuer and rehabilitator is not a self-designated title. It is a Federal crime to keep hummingbirds or any wild animal without a permit. Masear got all the required licenses and permits for wildlife-rescue. Further, she had to acquire all the equipment, cages, feeders and incubators before she could pass a state inspection.

Masear’s book covers one season in which she shares colorful stories of the people and hummingbirds with whom she comes in contact. Masear travels to a Holmby Hills mansion, a movie set and coaches a Malibu resident how to save a nest of fledglings on a branch hanging over a cliff above the Pacific Ocean. All types of people, from Goths to gardeners, at all hours day and night, do what they can to help the little birds.

Woven into each chapter are the amazing facts about these marvelous creatures. For instance: A hummingbird’s baseline body temperature is 105 degrees; the color of a nest and its construction style identifies the type of hummingbird; hummingbirds don’t eat ants and do eat over 400 fruit flies a day; there are 330 species of hummingbirds in North America and they only exist in the Western Hemisphere; 16 species breed in the US; they can dive at over 65 mph, weigh less then 4 grams, migrate up to 7,000 miles, and can impale the heart of an adversary in combat with their sword-like beaks!

Throughout the narrative, Masear shares the ongoing story and rehabilitation of Gabriel, the first hummingbird she saved before becoming a rehabber. Years later, the same bird shows up once again requiring her help adding to the mystery and magic of life.

LA rehabbers take in over 400 hummingbirds in a season. Along with the encounters of birds and humans, Masear has a very good rehab success rate. Of the 160 birds Masear cares for, 135 are released. But, it is what she learns about herself and others as she nurtures the birds to health that is equally compelling and inspiring. The humans who bring in the birds, more often than not, require nurturing as well.

With regular close contact and a deep compassion for the birds, Masear has come to know the subtle messages the birds relay through vocalizations and body language. Her close observations have made her an expert at analyzing their behavior and condition. The bird relationships force her to reconsider her own human condition and behavior.

The author shares not only her journey but how being a rehabber changed her life. Masear writes that she had an “…insidiously creeping midlife sense of disillusionment and lack of purpose to feeling gifted and necessary.” A black belt, Masear often turns to Lao Tzu for insight, patience and understanding for both birds and humans. This helps her cope with the stress of life, death and extreme rehab fatigue.

In the Los Angeles metropolitan area, thousands of hummingbirds have to coexist with 18 million residents. Hummingbirds die and get injured. State-sponsored and private non-profit wildlife organizations admit more than 1,000 hummingbirds into Southland rescue facilities.

This book is much more than just about hummingbirds. It’s a wonderful tale about the care and keeping of the wild creatures that exists around us and what they can teach us when we take time to not only observe and listen, but to show compassion.

I am incredibly impressed at the strength of character and resilience Masear musters to work with dying, injured or orphaned hummingbirds. It makes me appreciate the good work CVW columnist Janet McAfee and organizations like Loving All Animals do for the needy creatures in our valley.

Masear says at the end: “My job is to harness callers’ unchecked emotions, refine them, and turn them back out as something productive and purposeful, something that, despite man’s carelessness and nature’s indifference, reintroduces the beauty of life into our fallen world.”

Besides rehabilitating hummingbirds, Masear is rehabilitating people by helping them be more empathic, compassionate and conscious of all living things.