By Eleni P. Austin

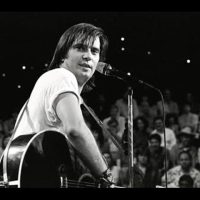

If you look up the word “rebel” in the dictionary, chances are the definition is accompanied a picture of Steve Earle. He seemed like a fresh new voice in Nashville, when he burst on the scene with his 1986 debut, “Guitar Town.” But Earle had been toiling in the margins of the music business for years before his big break.

Steve Earle was born in 1955 and grew up in Texas. He picked up the guitar at age 11 and by 13 he was pretty proficient. His first band, in the eighth grade, considered themselves Bluesmen, and they were inspired by Muddy Waters, Jeff Beck and Johnny Winter. But they were also rebelling against the popular music in their area, Country Western.

Earle dropped out of high school at age 16 and got married. By the time he was 19, he was divorced and had relocated to Nashville, bound and determined to make it as a musician. He worked odd jobs and haunted places like the Bluebird Café where he met his mentors, Texas singer-songwriters Guy Clark and Townes Van Zandt. He also married for the second time.

By 1975 he was playing and touring with Guy Clark. He got a job as a staff songwriter for a publishing house. Unsatisfied, he briefly returned to Texas, formed a band called the Dukes and began playing in bars and Honky Tonks there.

Back in Nashville by 1980, he signed a new publishing deal and artists like Johnny Lee and Carl Perkins had hits with his songs. Signed to Epic Records, Earle recorded an album’s worth of his own songs in a Neo-Rockabilly style that remained unreleased. Luckily, his talent attracted the attention of MCA Records producer, Tony Brown.

Severing his ties to Epic, Earle signed a seven album deal with MCA and released his debut, Guitar Town in 1986. The rollicking album firmly straddled the Rock and Country genres, and rocketed to the Top 10 of the Country charts.

Critics correctly connected Earle’s populist, everyman tunes with the music that Bruce Springsteen and John Mellencamp were making at the time. While his sound endeared him to Rock fans, it alienated him from traditional Country fans.

But Earle wasn’t interested in being popular, just authentic. His second album, Exit 0 arrived in 1987 and was credited to Steve Earle and the Dukes. The album rocked harder than his debut but, like Guitar Town it was nominated for two Grammys.

By the time he returned with his third effort, Copperhead Road in late 1988, Earle had been married and divorced three more times, and started delving deeply into drugs. The album incorporated elements of Bluegrass and Metal, and included collaborations with Irish Folk-Punkers, the Pogues and Bluegrass superstars, Telluride.

Earle seemed more politicized. The title track told the powerful tale of a Vietnam vet modernizing the family’s illegal Moonshine business by smuggling marijuana. Meanwhile “Snake Oil” labelled Ronald Reagan a con man/travelling salesman. The album was a hit on Rock radio and completed his break with the rigid constraints of Country music.

Professionally, Earle was riding high, creatively and commercially. Personally, Earle was also riding high, deep in the grips of a drug addiction. He continued to record. The Hard Way arrived in 1990, but his habits were affecting his talents. The album was slipshod, and for the next few years, music took a backseat to his addictions.

His answering machine (remember those?) advised callers “This is Steve, I’m probably out shooting heroin, chasing 13 year old girls and beatin’ up cops, But I’m old and I tire easily so leave a message and I’ll get back to you.”

Funny, but not so funny. His weight ballooned or plummeted, depending on his drug du jour, heroin or crack cocaine. MCA rejected his next record, choosing instead to release a live album, Shut Up And Die Like An Aviator. Not long after, the label terminated his contract.

In 1994 he was arrested for heroin possession and sentenced to a year in jail. He served 60 days and followed that with a stint in rehab. Luckily, his treatment worked. Clean and sober, Earle remarried his fourth wife, and worked on his 12 steps.

A year later, (and re-divorced from his fourth wife, Lou Ann), he released Train A’Comin, on the tiny, Winter Harvest label. It was a winning return to form, folky and contemplative it contained the beautiful ballad of remorse, “Goodbye.” On the strength of that material he was signed to Warner Brothers and released his masterpiece, I Feel Alright in 1996.

Resolutely sober and looking to stay that way, Earle entered the most fertile and most prolific period of his career. El Corazon arrived on the heels of I Feel Alright. In 1999, he released The Mountain, a collaboration with Bluegrass stalwarts, the Del McCoury Band. On “Transcendental Blues,” Earle’s left of center politics were at the forefront with “Over Yonder (Jonathan’s Song),” a track that memorialized a young kid on death row that Earle had befriended.

Of course the political shit really hit the fan two years later with his 2002 album Jerusalem. Earle included a song called “John Walker’s Blues,” which tried to understand the actions of American terrorist, John Walker Lindh.

Predictably, Fox News assumed Earle was condoning Lindh’s behavior and so Earle made the rounds to morning talk shows, attempting to rectify that mis-perception. Insisting he had sons close to Lindh’s age and that’s what motivated the song. His protestations fell on deaf ears.

Earle continued to make albums through the 2000’s. The Revolution Starts Now in 2004, and Washington Square Serenade in 2007, the latter reflecting his recent move to Greenwich Village. It also included contributions from his new wife, Country singer, Allison Moorer, and his son Patrick. (His older son, Justin Townes Earle, had just begun a promising music career of his own.)

Along the way, Earle had written a couple of books and began acting on two acclaimed HBO series, “The Wire” and “Treme.” In 2010, he released Townes, a tribute to his late mentor, and followed up with I’ll Never Get Out Of This World Alive in 2011 and Low Highway in 2013.

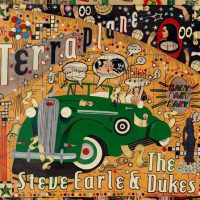

Sadly, his marriage to Allison Moorer has ended, leaving Earle feeling somewhat blue. So he decided to channel his sadness into creating his first-ever Blues record, Terraplane.

The album opens with the one-two punch of “Baby Baby Baby (Baby)” and “You’re The Best Lover That I Ever Had.” “Baby…” weds a Chicago shuffle rhythm to smoky harmonica notes and scuzztone, shang-a-lang guitar licks. On “Lover…”12 string acoustic chords interlace with electric riff-age and sawing violin fills. The lyrics on both are equal parts carnal and sardonic.

If it was possible for Bob Dylan’s “Highway 61 Revisited” and ZZ Top’s “La Grange” to have a love child, it might sound like “The Tennessee Kid.” Over a relax-fit rhythm and swampy guitar, Earle crafts the most erudite and literate Crossroads mythology ever.

As the Kid prepares to sell his soul “the monster raises himself up to the fullness of his stature, black wings eclipsing a sanguine Mississippi moon/Behold behemoth the trampler of infidels, he who sweeps away nations with the flick of his tail/Theopolis, Agrippa, Faustus, Paganini lurid and long is the tale of my prey, question not the ironclad bond of my surety/ Set down here in blood in your very own hand.” (Phew).

The Rolling Stones have always been a seminal influence for Earle, as a neophyte musician he set out to master the British Blues connoisseurs’ “Dead Flowers” on guitar. So it isn’t surprising that two tracks here pay sly homage to Mick and Keith’s bluesy beginnings.

“The Usual Time” recalls one of the Glimmer Twins’ first compositions, “Under Assistant West Coast Promotion Man,” (which they actually nicked from Buster Brown’s “Fannie Mae”). Wheezy harmonica tones crest over a leap-frog rhythm and twangy guitar as Earle hopes for a late night dalliance.

“Go Go Boots Are Back” echoes the lean economy of “Exile On Main St” era Stones. The lyrics offer a tart reminder everything old is new again. “Go Go boots are back and I think that’s outasite, the kids don’t call them that but they’re Go Go boots alright/I was just a little boy the first time they came around, but my sister had her some and she wore ‘em up town.”

Of course Earle addresses his recent heartbreak on “Ain’t Nobody’s Daddy Now” and “Better Off Alone,” each track offers different sides of the same coin. The arrangement of the former borrows it’s mojo from traditional New Orleans’ Second Line music, anchored by knockabout percussion and wicked guitar licks. Here Earle seems to relish his newfound bachelorhood. “Got a baby on the Eastside, a honey on the West/Got a woman uptown, but downtown gals are best.”

The instrumentation on the latter is spare. Simmering electric guitar underscores Earle’s lonely isolation and the conviction that perhaps he is meant to stay single. “It’s clear the story’s shown I’m better off alone.”

Other interesting tracks include the sepia-toned “Gamblin’ Blues,” and the sunny Dixieland ramble of “Baby’s Just As Mean As Me.” Finally, the shambolic Country Blues of “Acquainted With The Wind” weirdly, (and winningly) channels Spinal Tap’s British Invasion Blues parody “Give Me Some Money.”

The album closes with the Crawling King Snake shake of “King Of The Blues.” Over gut-bucket bass lines, swampy guitar and a steady rhythm, Earle spins a verbose creation yarn declaring “I’m the king of the blues, the 13th in line, the first of my name the last of my kind/One foot in the grave and one hand on the handle of time/Descended directly from St. John the conqueroo/I’m the high priest of heartache and the king of the blues.”

Befitting Earle’s rebellious nature, Terraplane could hardly be considered a “traditional” Blues album. It’s clear he remains inspired by the same stuff that excited him as a kid, Canned Heat, Chess Records and Texas Blues legend, Johnny Winter. In fact, the record is dedicated to Winter, who passed away in 2014.

Steve Earle remains a protean talent, even as he begins touring behind Terraplane he is already writing an original Broadway musical and planning an album with Shawn Colvin. For now, his fans can savor this Bluesy excursion.