By Eleni P. Austin

In the Winter of 1963, America was reeling from the assassination of President John F. Kennedy. His administration and young family had instilled a new feeling of hope and enthusiasm in the country. His vision of a “New Frontier” was shattered in late November on the sunny streets of Dallas. The United States was collectively in mourning, in early 1964, one event pulled us out of our grief was the arrival of the Beatles.

The Beatles were already enormously popular in Great Britain, the Liverpool four-piece had taken the country by storm and they’d spent all of 1963 perched at the top of the U.K. charts. When they debuted in the U.S. on the Ed Sullivan in February of 1964, they were exactly what the doctor ordered. Their music was a jolt to the system that rescued the nation from it’s collective malaise.

Currently, America is experiencing truly tumultuous times. The recent Presidential election has divided the country, often times putting family members at odds. Many are depressed and grieving for what could have been. While music isn’t the ultimate panacea, it can get us through tough times. That’s where the Weeklings come in.

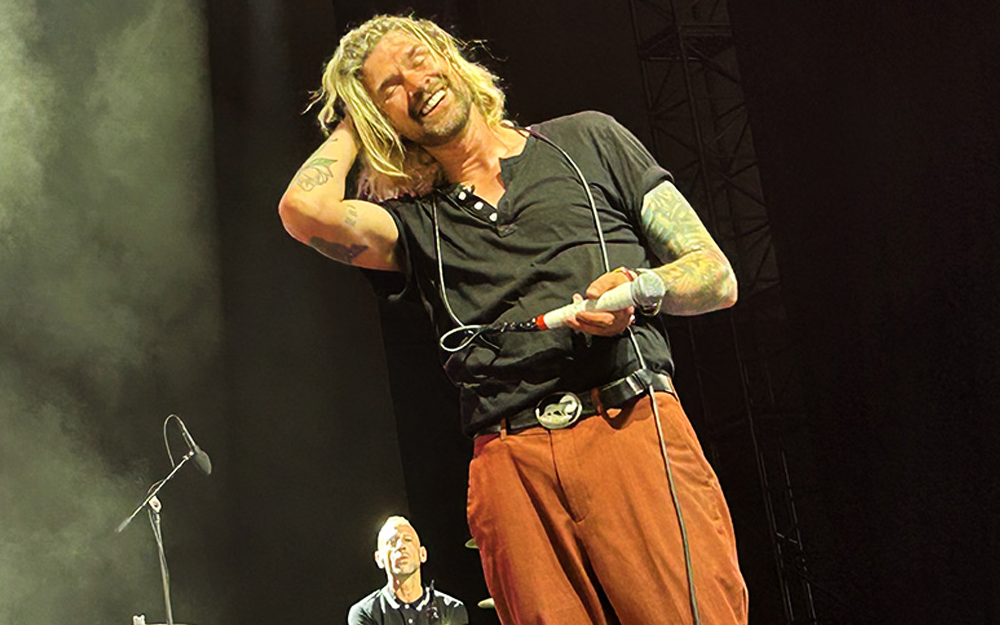

The Weeklings hail from New Jersey, a quartet of players who make their living in the music industry. Multi-instrumentalist Glen Burtnik has played in permutations of Electric Light Orchestra and Styx, co-writing hit songs with guitarist Bob Burger for the latter.

In turn, Burger has shared stages with Meatloaf, Hootie & The Blowfish and Robert Palmer. Both have also lead parallel careers fronting their own bands. Lead guitarist John Merjave has played with Billy Preston, Ronnie Spector and Micky Dolenz. Drummer Joe Bellia has spent many years pounding the kit for Southside Johnny And The Asbury Jukes.

All four were weaned on Beatles music. They originally came together playing Fab Four songs at annual conventions. The chemistry between them felt electric, but they didn’t want be pigeonholed as a Beatles tribute act. So they opted to use the sunny sound of the British Invasion and Power Pop as a template, writing original songs and sprinkling in rare and lesser known Lennon & McCartney compositions.

Taking a page from the Traveling Wilburys playbook, the four-piece first adopted rockin’ pseudonyms, Glen became Lefty, Bob was Zeek, John pulled no punches as Rocky and Joe morphed into Smokestack. Like the Ramones, they took the shared surname of Weeklings, (perhaps a nod to their non-Charles Atlas physiques). As an homage to their Liverpool avatars, who put the Beat in Beetles, they put the Week in Weakling.

The band quickly signed with Jem Records and recorded Monophonic, it was released in the Spring of 2015. The 12 track debut split the difference between six irresistible Weeklings originals and five obscurities from Lennon & McCartney, plus one from George Harrison. Critically, the album was well received and their fan base continued to grow.

For their second long-player, the Weeklings actually traveled across the pond to the Mop-Top mecca of Abbey Road studios. In the sacred space of Studio 2, they recorded eight originals and four Beatles rarities. The result is the aptly named Studio 2.

For their second long-player, the Weeklings actually traveled across the pond to the Mop-Top mecca of Abbey Road studios. In the sacred space of Studio 2, they recorded eight originals and four Beatles rarities. The result is the aptly named Studio 2.

The album crackles to life with “Morning, Noon & Night.” Jangle-Pop electric guitar and growling bass lines connect with a rippling rhythm and Mersey Beat harmonica. Sugar-rush harmonies coalesce, at once treacly and tart. Much like “Every Breath You Take” from the Police, the lyrics can be interpreted two ways. The sweet story of a stalwart boyfriend patiently slogging through a long distance relationship, or a treatise on stalking, featuring a disciplined weirdo spying on his prey “three hundred sixty five days, every morning, every noon and every night.”

Of course, ground zero for Rock N’ Roll is the primitive cool of progenitors like Chuck Berry and Elvis Presley. Both “Don’t Know, Don’t Care” and “Little Elvis” pay homage to these trailblazers. “Don’t Know…” is raucous, rough and tumble. It opens with a spiky guitar riff that folds into a duck-walking back-beat. Defiant lyrics subscribe to the “what’s good for the goose” philosophy, calling out an unfaithful girlfriend for “makin’ out with Joey, Jimmy, Johnny or Clyde” before making plans to indulge in the exact same behavior; “I got my eye on a pretty little child, she’s got the kind of lovin’ makes a boy run wild.” On the instrumental break, the tempo accelerates wildly. A pounding tom-tom rhythm cushions a blistering guitar solo that pivots and pirouettes.

“Little Elvis” is a stompy delight, powered by an insistent handclap beat and spiraling guitar licks that echo the exuberance of the Beach Boys’ “I Get Around” as well as the Isley Brothers’ “Twist & Shout.” The lyrics spin an apocryphal tale of the King’s diminutive doppelganger wreaking havoc on the female population; “He bats 1,000 with the local chicks, he’s been this way since 1956/4 foot 11 in his platform heels, but he knows how to make a woman feel.”

The album’s best tracks capture the essence of ‘60s Pop like lightning in a bottle. If it was possible for the Byrds and the Monkees to have a musical love child, it would sound like “You’re The One.” The tune is tethered to a cantering meter, loping bass and twangy guitar. Lyrics note that despite life’s uncertainties love remains constant; “And every twist and turn just makes me dizzy and confused/And every road becomes the road that’s leading me back to you.” The melody mines the same sweet territory as the Byrds’ “Mr. Spaceman,” along with the Monkees’”What Am I Doing Hangin’ Round.” Meanwhile, taut and economical guitar solo echoes the concise Rockabilly of Carl Perkins and James Burton.

The tinkly piano notes and shimmery vocals of “But Love Can,” recalls the pure Power Pop of Badfinger and the Raspberries. The song’s slightly sappy message is that love will prevail. There’s even a gently weeping guitar solo, as the track drifts off on a gentle cha-cha-cha rhythm.

Finally, “Next Big Thing” is a rollicking rave-up anchored by a stutter-step rhythm, boomerang bass lines and ricocheting guitar riffs. Humble-brag lyrics bemoan a break-up despite consistently bad behavior; “Never thought she’d set me free, never dreamed she’d fly, always thought she’d wait for me/ And never realized I could be so rude and crude, and I could keep her hanging on a string/Now I’m looking for that woman, but she’s looking for her next big thing. Prickly guitar riffs punctuate each caustic refrain. Rocky Weekling unspools an incandescent solo that bobs and weaves through the melody, alternately floating like a butterfly and stinging like a bee.

The last two original tracks, “Stop Your Runnin’ Around” and “Melody” display the yin yang dichotomies of the band. The former locks into a see-saw groove that swaggers with soul. Candy-coated harmonies can’t conceal the betrayal of casual infidelity; “You’re treatin’ me bad, I’m lettin’ it slide/You’re makin’ me sad, hurtin’ my pride.” Tensile guitar riffs underscore the final ultimatum: “You better stop your runnin’ around.”

The latter is wistful and willowy, chiming acoustic guitars lattice over a graceful tune. The lyrics offer a sharp analysis on the power of music; “Irresistible progression, melody, melody, a cadence that defies convention/Echoing a pure reflection, each note follows in perfection, take me down again.”

The final four songs on Studio 2 focus on Lennon & McCartney compositions that never appeared on official Beatles recordings. Of course even the Beatles’ throwaways are uncut gems bordering on masterpieces. The earliest cuts, “You Must Write” and “Some Days,” date back to 1960. “You…” is a reverb-drenched rave-up, featuring skittery guitar, slap-back bass and a propulsive beat. “Some Days” employs Surfin’ n’ Spyin’ guitar licks over a sturdy handclap rhythm.

“Because I Know You Love Me So,” is a countrified outtake from the “Get Back” (“Let It Be”) sessions. It’s Bakersfield-meets-Liverpool, cross-pollinating Honky Tonk guitar with a rhythm slightly poached from the Fab Four’s own “She’s A Woman.” The almost acapella “Love Of The Loved” closes out the set. A halting ballad written by Paul McCartney in 1962, the lads recorded it for their audition at Decca Records, but their version has never been officially released. Instead, they gave it to Mersey chanteuse Cilla Black, who had a modest hit with it a year later.

The Weeklings manage the neat trick of distilling the halcyon sounds of the ‘60s and early ‘70s without ever sounding secondhand or derivative. Indelible melodies are matched with crackling arrangements and crisp instrumentation. No one can completely escape from reality, but as soon as the needle hits the grooves of Studio 2, you’re bound to forget that your microwave is recording your every move.