By Eleni P. Austin

Musically, Chip and Tony Kinman have always been ahead of the curve. When Punk Rock was in its infancy, the brothers formed The Dils, relocating from Carlsbad, California to San Francisco in 1977. The seminal outfit released a handful of singles, including classics like “I Hate The Rich” and “Class War.” (The Punk band playing on stage at the Roxy during a pivotal scene in Cheech & Chong’s Stoner-Cinema classic, “Up In Smoke,” that would be the Dils). They even served as the opening act for the Clash on their very first American tour. They were only together for two years before calling it quits in 1979.

Partnering with drummer Slim Evans and guitarist Alejandro Escovedo (also a veteran of the San Francisco Punk scene and a part of the Escovedo clan which included Uncles Pete and Coke from Santana and soon-to-be Prince protégé Sheila E.), the Kinman brothers began charting a new course as Rank and File. The four-piece practically invented Cowpunk, a hybrid genre that fused, you guessed it, Country and Punk music. They spent time woodshedding in Honky Tonks and dive bars in Texas before signing with Slash Records.

Their nearly perfect debut, Sundown arrived in 1982. Unfortunately, Slim and Pete both moved on after the first album. The brothers recruited new musicians, recording two (less perfect) follow-ups, Long Gone Dead and a self-titled effort, before pulling up stakes in 1987. The Dust had barely settled before Chip and Tony had created Blackbird.

Essentially a two-man operation, their third band in less than 10 years is best described as Post-Punk Electronica. Sharp, fraternal harmonies remained intact but they were swathed in layers of guitars and held together with the help of a scuzzy Yamaha RX-5 drum machine. Between 1987 and 1994 they released three albums. Taking a page from Peter Gabriel’s early career, each Blackbird album was confusingly self-titled.

After Blackbird flew the coop, Tony and Chip managed to corral drummer Jamie Spindle and formed Cowboy Nation. The trio mixed traditional Cowboy songs with Country standards and keen originals. Burnished vocals paired with spare instrumentation drifted across three amazing records before this latest collaboration came to a close.

In the ensuing years the brothers traveled different paths for a bit. Tony formed the band Los Trendy, which lasted a few years. Chip recorded a Punktastic solo album, and spent time raising his family. A few years ago, he came roaring back with his Psyche-Punk-Rock-Blues combo, Ford Madox Ford. Although Tony wasn’t in the band, he produced and engineered FDMDXFD’s 2018 debut album. The brothers’ had discussed reuniting the Dils, but before those plans could come to fruition, Tony was diagnosed with a very aggressive form of cancer. He sought treatment, but sadly, he lost his battle in May, 2018.

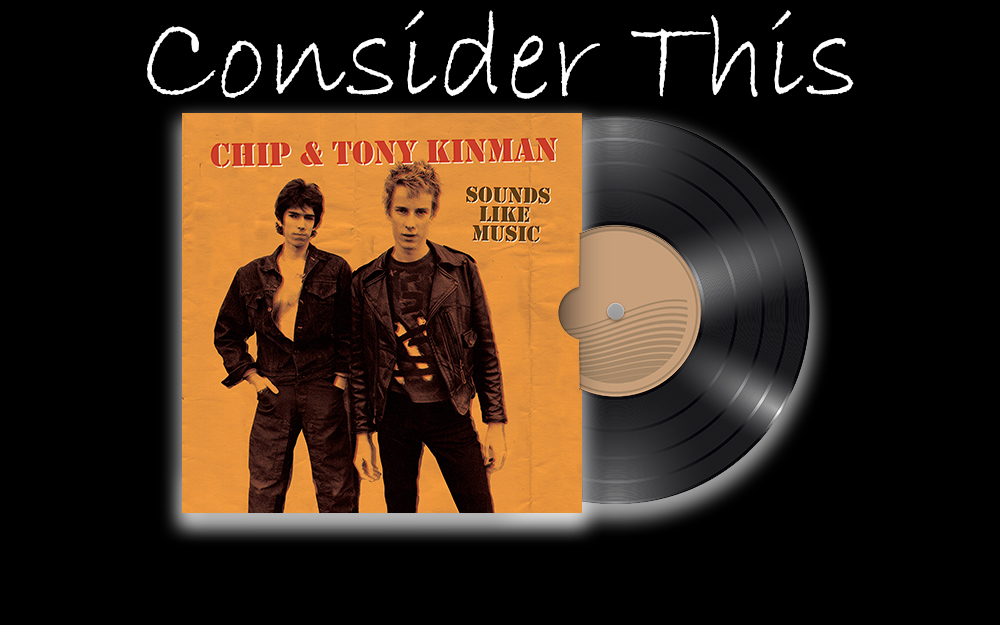

Throughout the years, there has never been a career overview of the Kinman Brothers decidedly unorthodox oeuvre. Luckily, the fine folks at Omnivore Recordings have sought to remedy that by releasing Chip & Tony Kinman, Sounds Like Music. The 22-song set includes music from the Dils, Rank And File, Blackbird and Cowboy Nation.

The album gets down to business with “Real Style” a taut instrumental that lands somewhere in between the Meters’ “Tippi-Toes,” late ‘70s Devo and some long lost love theme from a Pee-Wee Herman movie. Idiosyncratic and playful at the same time, it serves as an oddly perfect intro.

Chip and Tony never followed anyone else’s blueprint, so it’s wholly apropos that the track-list is all over the map, completely flouting chronological order. Only one song represents the Dils’ minimalist output. “Folks Say Go” actually pre-dates their first official single, “I Hate The Rich.” Powered by righteous teen angst, the song is primal, primitive and seems on the verge of spontaneous combustion.

Surprisingly, Rank And File are only allotted six tracks here. There are alternate versions of “Rank And File,” “Amanda Ruth” and “Lucky Day,” from the Sundown Record. “Rank…” is rough and ragged, featuring a pummeling backbeat, search and destroy bass and scorched earth guitar. It’s less Cow and more Punk, as sneering lyrics chronicle the plight of the working man; “Shift to shift, in and out, I give and they take/I punch that clock and punch it hard enough to break.”

“Amanda Ruth” remains as winsome as ever, powered by ramshackle guitar riffs, walking bass lines and a locomotive rhythm. Tony’s boom-chicka-boom basso vocals intertwine with Chip’s yodel-y tenor. The lyrics recount a burgeoning Punk Rock romance that mines the giddy sensations of Young love. It’s easy to see why the Everly Brothers covered the song when they briefly reunited in the mid ‘80s.

“Lucky Day” is a broken-hearted lament that blends mournful harmonies, rumbling bass and a tick-tock beat; the guitar solo on the instrumental break, trills, chimes and rings, providing something of an antidote to the song’s forlorn feel.

Also included here are three Rank And File tracks that somehow didn’t make it onto the band’s original long-players. “Citizen” dates back to 1978 and is a frenetic mix of whiplash guitar riffs, slapdash bass, pounding drums and yowly vocals. The melody and arrangement seems more Clash than (Johnny) Cash.

Both “Restless” and “Landslide” were written during Rank & File’s final days. The former is propelled by a jittery beat and twangy guitar. Chip is out front and the brothers’ always concise lyrics seem to be warning their fans the end is nigh; “You can yearn for the good old days, but I’m restless.” On the latter, their disparate influences effortlessly coalesce. Rickety guitar connects with boomerang bass and a breakneck beat. The lyrics spin a saga of an apocryphal journey. Slightly more Hee-Haw than mosh pit, it’s an elastic little Rocker that illustrates how seamless their hybrid sound had become.

The balance of the album is given over to Tony and Kip’s most ambitious band, Blackbird, where genres are immediately blurred. The songs range from the industrial static of “Me Too,” the percussive assault of “Dope,” the sonic collage of “Candy” and the shuddery dystopia of “Dream On.”

A measure of social conscience colors both “Liberation” and “Revolution.” On the former, a click-track beat, buzzy guitars and robotic vocals collide. The lyrics warn against complacency; “Don’t count your blessings when there’s work to be done.” The latter layers loopy synths over feedback-drenched guitars and a bludgeoning beat. The chorus is a clarion call; “You better wake up, cause revolution is coming.”

Blackbird reinterprets a couple of classics, adding shards of guitar and some ethereal shimmer to the Cowpoke Folk of “Old Paint.” There’s also a fairly faithful version of “Jersey Girl.” The Tom Waits original gained international attention when Bruce Springsteen’s version closed out his “Live/1975-85” box set. Chip and Tony’s vocals intertwine as guitars keen like bagpipes, caressing this heartfelt Doo-Wop pastiche.

Blackbird consistently subverts expectations. If Duke Ellington, the Stooges and Bob Dylan (circa his Subterranean Homesick Blues days), ever collaborated, it might sound like the syncopated Punk of “Blue Hair.” Country underpinnings warm the chilly techno textures of “She’s Real.” Meanwhile, “Perfect” seems echo the pithy Proto-Punk of the Velvet Underground and anticipate the laconic charms of Yo La Tengo.

Chip and Tony kept the Cow and scrapped the Punk when they formed Cowboy Nation. CN is afforded just two tracks here, both are alternate versions that originally appeared on the band’s final album, Cowgirl A-Go-Go. First up “Paniolo” is a spirited ode to Hawaiian cowboys. The arrangement is accented by speed-shifty acoustic guitars and yodel-rific harmonies that hug the melody’s hairpin turns. “Rebel” moves at a locomotive clip, adding high lonesome guitars and some rumbling bass. Tony takes the lead here, and once again Chip chimes in, deftly shading his brother’s authoritative growl. The lyrics offer a cryptic tribute to their parents, Dixie Pearl and Harold J. Kinman.

The album closes with one last Blackbird cut, “All The Same.” A thick slab of grinding gears, off-kilter percussion, wheezy synths, scabrous guitar and hazy vocals, it adds yet another color to the Kinman Brothers’ kaleidoscopic sound.

Of course, this collection isn’t definitive, (box set, please!) It would be nice to hear some live stuff from each era. But it offers a snapshot of the Kinman Brothers musical evolution from political Punk rebels to alt.country architects to Techno provocateurs to Cowboy classicists. Even though they weren’t completely appreciated in their own time, their music clearly continues to resonate as is evidenced by Ty Segall’s trenchant take on the Dils’ quintessential cut, “Class War.”

Playing through a song, Tony once quipped to his brother, “Well, Chip, that was pretty good, now make it sound like music.” That’s pretty much what the Kinman Brothers did. Who else would have thought to synthesize “Git Along Little Dogies” and I Wanna Be Your Dog?” By following their muse and never compromising, they created Music that endures.