By Haddon Libby

This year marks the 140th Labor Day in the history of the United States. The long weekend is traditionally considered as the end of summer and a last break before we returning to work and school schedules.

Labor Day is intended to celebrate the American worker. The holiday’s roots can be found in the late 1800s – a time when factory workers suffered with long hours and hazardous work conditions. Back then, workers could put in twelve-hour days for six or seven days a week. Pay was poor due to influxes of immigrants from Europe who were hungry for any job they could get. Sadly, children as young as today’s kindergarten students would work grueling hours as well. A factory worker had a hard life that was typically in a poorly vented, unsafe space.

To try and combat these harsh conditions, labor unions sprouted up. Workers joined as they collectively tried to negotiate for living wages, safer conditions, and breaks.

Labor Day is thought to have begun on September 5th, 1882, in New York City. On that day, more than 10,000 workers took an unpaid leave from their jobs to march from City Hall to Union Square.

Marches and strikes began occurring with increased frequency. The cornerstone of most labor demands was an eight-hour work day, a minimum wage, and safer working conditions.

Complicating matters, radical elements of some labor unions were political. Where the United States is and was a democratic republic, some labor groups championed socialism, communism or anarchy.

The 1886 Haymarket Riot in Chicago became violent when someone threw a bomb at the police. The police responded by shooting into the crowd. By the end of the riot, eight policemen and workers were killed. Many believe that labor organizer August Spies, a German immigrant, wanted the conflict. As a known anarchist, Spies used the event to try and gain traction for his political views.

Between the marches and increased conflicts, a xenophobic wave started to cross the country. This created distrust between these workers and people of different socio-economic classes.

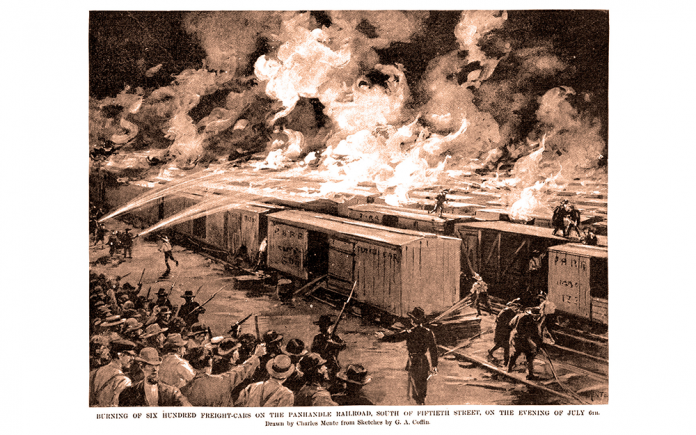

Over the next eight years, tensions between workers and employers continued to worsen. The U.S. economy was in a recession which acted gas on a smoldering fire. On May 11th, 1894, tensions reached a head as workers of the Pullman Car Company (train cars) went on strike. Problems between the company and workers started once union representatives were fired and worker wages were cut. This led to a nationwide strike against rail companies that used Pullman cars. By June, 125,000 railway workers were on strike. The strike crippled transit and commerce and brought the already fragile U.S. economy to a near halt.

With this as the backdrop President Grover Cleveland signed Labor Day into law which gave workers a day off.

It would take another forty-four years for the Fair Labor Standards Act of 1938 to become law. The 1938 law was the first time that child labor was restricted to those over 14 years of age (although they could still work in agriculture). Hours were limited until the children reached 16. The most dangerous jobs were withheld until they were deemed to be adults at the age of 18.

Labor Day was originally established to ‘throw a bone’ to overworked and underpaid factory workers. It was done to try and lower tensions between first generation immigrants and earlier American immigrants.

Where unions served a critical role in developing worker rights, membership is currently at its lowest levels in seventy years. Where roughly one in three workers were part of a union in 1954, only one in ten workers today are part of a union.

Haddon Libby is the Founder and Chief Investment Officer of Winslow Drake Investment Management. For more information on our locally-based, award-winning Registered Investment Advisory business, please visit www.WinslowDrake.com.