By Eleni P. Austin

When David Bowie died in 2016, two days after his 69th birthday, it felt like a punch in the gut, to fans across the globe who saw him as a kind of Rock N’ Roll avatar. Nearly three years later, it’s still a raw and devastating loss. Like Elvis, like John Lennon, Joe Strummer (and later Prince), his work feels unfinished. He was an innovator and his music continues to resonate.

Born David Jones in Brixton, London England, like most post-war kids, his interest in music was sparked by technicolor American Rock N’ Roll and the darker hues of Rhythm & Blues. Elvis Presley and Little Richard were early touchstones, then his older brother introduced him to Jazz. He learned the saxophone and officially began his music career at age 13. Early bands included the Konrads, the King Bees, the Mannish Boys, The Lower Third, the Buzz and the Riot Squad. By 1967 he became David Bowie, partly to lessen confusion with another British singer named Davy Jones who had achieved recent fame and notoriety as one of the Monkees.

By the dawn of the “Me Decade” Bowie had successfully shape-shifted from a Mod Dandy to an Anthony Newley-esque crooner to an effete hippie with Pre-Raphaelite ringlets. He had also had his first commercial success with his hit single “Space Oddity.” In a career that spanned nearly half a century, he hopscotched from one musical genre to the next. Rather than follow trends he anticipated them. He connected with producer Tony Visconti in 1970. Over the next two years he wrote and recorded his most enduring efforts, The Man Who Sold The World, Hunky Dory and The Rise And Fall Of Ziggy Stardust. Those records were a culmination of his myriad Influences.

Throughout the ‘70s, he created personas like Ziggy Stardust, Aladdin Sane and the Thin White Duke. Married with a young son, he proudly proclaimed his bisexuality. A devastating cocaine habit prompted him to retreat to Berlin and create an ambient triptych of albums with producer Brian Eno. Rehab’ed and revitalized by 1980, he made his Broadway debut as the lead character in “The Elephant Man.” He also released his 14th studio album, Scary Monsters a tensile combo-platter of Punk and Glam-Rock.

Three years later Bowie reached his commercial peak with his Let’s Dance album. Embracing the day-glo New Wave era on his own terms, the record featured the guitar stylings of Texas Blues purist, Stevie Ray Vaughan. Unfortunately, the synergy didn’t last and he spent the rest of the ‘80s in a creative slump. In an attempt to recharge his batteries, he formed the Noise Rock band Tin Machine. Their two albums were interesting, but commercial failures.

As the ‘90s dawned, and Grunge became the musical lingua Fraca, Bowie had finally found happiness when he met and married Somali Super Model, Iman. Musically, however, he seemed lost. He quickly championed emerging genres like Jungle, Drum & Bass and Industrial music. But, for the first time it felt as though he was pursuing trends rather than forging them. By the turn of the 21st century, David and Iman welcomed a daughter, Alexandria. Reconnecting with Tony Visconti in 2002 they collaborated on Heathen released that year, and Reality which arrived in 2003. Both found him embracing his legacy and receiving his best reviews in nearly 20 years.

While on tour in 2004 he suffered a heart attack on stage and received an emergency angioplasty. Cancelling his tour, he retreated from the public eye. Never officially retiring, he contributed to other artists’ projects like TV On The Radio and David Gilmour and in 2006, he received a Lifetime Achievement Grammy. Finally, after a 10 year hiatus, he released 24th studio album, The Next Day in 2013. It was a critical triumph, a tour de force. Bowie was back and operating on all cylinders. Sadly, this momentum was not to last, a year later he was diagnosed with liver cancer.

He never made the news public, instead Bowie concentrated on his newest project; creating music for “Lazarus” an Off-Broadway show based on the character he played in Nicolas Roeg’s baroque Sci-Fi Film, “The Man Who Fell To Earth.” Collaborating with Irish playwright Enda Walsh, he wrote new songs and reconfigured some Bowie classics. Before the show opened, he quietly booked time at a recording studio, blocks away from his New York home. Relying on Tony Visconti, they enlisted a quintet of Jazz musicians and set about recording the music he had created for “Lazarus.” The result was an elegant seven song suite entitled Blackstar. His 25th studio album, it arrived on his birthday, two days before his death and served as an elegiac parting gift to his fans.

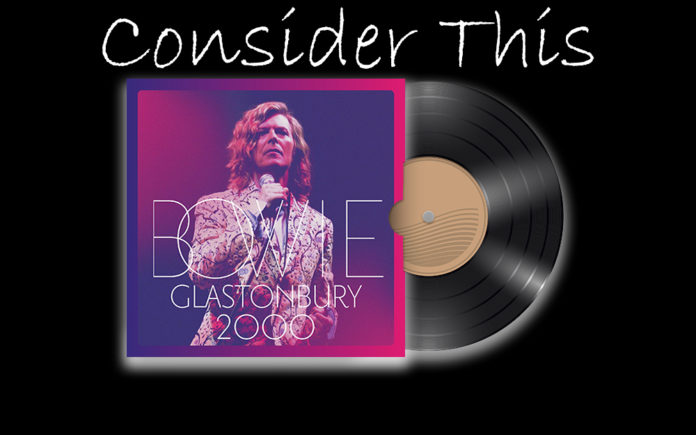

In the last couple of years, several posthumous collections have been popped up, mostly concentrating on live sets. Throughout his lifetime, he recorded numerous live efforts that have spotlighted different eras myriad musical genres. But there’s never been a live show that felt career defining. Perhaps this was because Bowie willfully closed the door on performing his “hits” following a 1990 tour devoted to fan favorites. Now Parlophone Records has bridged that gap by releasing Glastonbury 2000. Parts of this concert has been available on different media, But this two CD + DVD set, (which is also available as a 3 LP set), presents the entire 22 song concert.

The venerable British festival was in its infancy when he played there in 1971, for maybe 3000 people. His career was beginning to gain traction, and he was resplendent in what Bowie termed his “Bippity Boppity” hat, flared bell-bottoms, cape and cane. For the 2000 show, which attracted 120,000, his flowing ensemble was inspired by that original outfit.

The album opens with a sentimental, albeit Jazzy take on “Greensleeves” from pianist Mike Garson (a Bowie sideman since 1973). His light and airy version quickly quiets the crowd’s insistent chants of “Bowie..Bowie,” until the man himself hits the stage, as the drummer counts off and the band launches into a lush rendition of the Jazz standard, “Wild Is The Wind. The tender ache of his vocals, coupled with rippling piano notes and supple guitar, feel as revelatory as it did when it first appeared on his 1976 album, Station To Station.

Actually, it is the record he revisits the most in this set. That album, along with it’s predecessor, Young Americans, delved into a style Bowie dubbed “Plastic Soul,” it also ushered in his “Thin White Duke Persona.” That svelte alabaster duke-iness reemerges on the suave seduction of “Stay.” The Metallic Funk of the melody is enhanced by the muscular riff-age of Earl Slick, the gunslinger glides around prowling bass lines and a stop-start rhythm. “Golden Years,” which closes out the first disc, has only been played live only a handful of times, which seems inexplicable. From it’s opening, epochal power chords to the call-and-response between Bowie and His backing vocalists, and the ballast of rubbery bass and a whip-crack beat, it remains Infectious and authentically Soulful. Station’s ambitious title track gets it’s full 11 minute airing on disc two. The labyrinthine epic unfolds with dizzying pomp and circumstance accented by stuttery percussion, spiraling guitar pyrotechnics and a sultry wash of keys. Midway through he proclaims “It’s not the side-effects of the cocaine, I’m thinking that it must be love.”

The rest of the ‘70s is well-represented. “Hunky Dory” tracks include “Changes,” and “Life On Mars?” The former offers a cogent commentary on artistic reinvention. The irresistible melody Is buoyed by a staccato rhythm and Garson’s sparkling player-piano runs. Bowie’s vocal delivery is positively giddy as he proclaims “time may change me, but I can’t trace time.” Although the latter was originally written as a parody of Frank Sinatra’s defiant anthem, “My Way,” the song has taken on a life of it’s own. Surrealistic lyrics like “It’s on America’s tortured brow, that Mickey Mouse has grown up a cow,” are swaddled in billowy piano notes that take on a Classical lilt.

Bowie’s Berlin trilogy is compressed into the tensile anthem “Heroes.” Written after he witnessed his friend Tony Visconti embracing a back-up vocalist by the Berlin Wall, it morphed into a tale of young lovers from East and West Berlin. The song would take on greater significance when he performed it following the terrorist attack on 9/11. Here it’s lean and stripped-down. “Fame” from Young Americans is a still a sly slice of Doo-Wop Funk. Meanwhile, the dystopian Glam/Punk crunch of “Rebel Rebel” was a calculated farewell to his androgynous period. Powered by a hulking backbeat and that signature guitar riff, the tune simply crackles with authority.

Happily, this set makes some room for some of Bowie’s more outlier tracks like “Absolute Beginners,” “All The Young Dudes” and “Under Pressure.” It’s apropos that “…Beginners” is beguilingly cinematic since it was written for The 1986 film that Bowie had a small part in. The movie is set in late ‘50s Great Britain, and the song is sweeping, Jazzy, and grandiloquent, thanks in part to His swoony vocals.

“All The Young Dudes” was originally written to revive the flagging fortunes of Mott The Hoople, who were set to break up. The band took the Glam Rock anthem to #3 on the British charts. Containing the classic couplet “Television man is crazy saying we’re juvenile delinquent wrecks, I don’t need TV when I got T.Rex,” this version feels both stately and shambolic. Finally, “Under Pressure,” a hit collaboration with Queen. It subtly matched Freddie Mercury’s stentorian grace with Bowie’s calculated cool. Freddie’s part is filled by bassist Gail Ann Dorsey, making it feel all the more heartbreaking.

His commercial twin peaks of Ziggy and Let’s Dance get two cuts a piece. The “Ziggy” title track is a Glam/Metal hybrid, while “Starman” soars to celestial heights. “China Girl” feels sleek and shiny and “Let’s Dance” begins with courtly Spanish guitar, locking into a seductive Samba groove on the first few verses before it truly kicks into gear. Both songs feature blistering guitar solos from Earl Slick, building on the late Stevie Ray Vaughan’s Bluesy blueprint.

Ironically, the only songs here that haven’t aged well, are the ‘90s entries; “Little Wonder,” “Hallo Spaceboy” and “I’m Afraid Of Americans,” which closes the show. Throughout, Bowie is charming and flirty, offering up witty anecdotes and poking fun at his own vanity. His crack band follows along, hugging every hairpin turn.

Even after he’s gone, David Bowie still feels two steps ahead of the zeitgeist. All those years ago, when he insisted we “turn and face The strange” he didn’t tell us we’d be doing it alone. Listening to this album will make you miss him less, and then you’ll miss him all the more.