By Heidi Simmons

—–

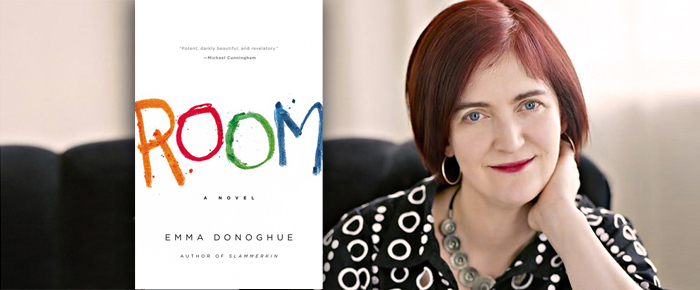

“Room”

by Emma Donoghue

Fiction

——

It’s horrific that human trafficking and sex slavery is happening today. It’s hard to believe that people can disappear and live as prisoners right in our own communities. In Emma Donoghue’s Room (Little Brown and Company, 336 pages) a woman and her son must not only figure out how to escape captivity but survive the trauma.

Five-year-old Jack tells the story. It’s his birthday and his mother, Ma, has made him a cake. Ma does everything she can to create a sense of celebration – a party with decorations and a gift. But Jack’s special day is pretty much like every other day of his life in the 11×11 foot space he calls “Room.”

Jack personifies and names objects in the tiny space that he and his mother inhabit. Like friends, there is Rug, Table, Lamp, Skylight, and “Meltedy” Spoon, which has a “blobby” handle after it melted on the stove. Jack likes the spoon best because it’s different from the others.

Ma dictates Jack’s days. She teaches him to read, makes him exercise and allows for watching television. Although Jack wants to watch more TV, Ma says it will “turn his brain to mush.” He has five books. Mother and son sing songs and play games together. One game is called “Corpse” where Jack fakes being dead.

Jack has Ma tell the story of his birth. There is a stain on Rug where Jack was born. Ma says he was created in heaven like Baby Jesus.

At night, Jack sleeps in Wardrobe. He is hidden there from the regular visitor he calls Old Nick. (Unbeknownst to Jack, this is his captor and father!) Ma won’t let Old Nick see or touch Jack. Jack stays quiet and counts his teeth or the squeaks Bed makes until Old Nick leaves. He looses count after 357 or falls asleep. Old Nick does not bring Jack a present for his birthday.

At his next visit, he brings Jack a toy. When Jack cries out from the wardrobe, Old Nick wants to take a look at the child. Ma tries to stop him but Old Nick beats her. Old Nick punishes Jack and Ma by turning off the power to their room, cuts back on their food and refuses to provide warm clothing. Old Nick tells Ma he has lost his job.

Ma comes up with a plan to escape Room. But Jack will have to leave without Ma. This terrifies little Jack. He wants to wait until he’s six. But Ma refuses.

Jack has only heard stories of the outside world. He has only seen “Outside” on television. He has trouble understanding what is real.

Ma’s plan works and Jack gets away. He’s a hero and Ma is saved.

But the trauma doesn’t stop once Jack and Ma are free. Now they must cope with the bigger world outside. Ma has been captive for seven years! Jack has never seen the sun or felt a breeze on his face. Then there’s the paparazzi who want pictures of Jack and Ma for the papers. Outside is frightening and strange to Jack.

This is a terrifying story even with the happy ending. All to often the reality of this fictional story is true. In recent headlines, several women have been able to escape similar circumstances — some with their children who were born during captivity.

Author Donoghue’s narrative approach is clever. Through the voice of an innocent child, the reader is exposed to the horrific life Ma and Jack lead. The child knows no other existence. He does not condemn or judge their life or that of his captor’s. He simply makes do with what he has and the love he shares with his mother. Without anything to compare his life to, in Jack’s eyes, his world is basically perfect.

This makes Jack an unreliable narrator. He cannot and does not fully understand the circumstance. His worldview is completely limited to the room and what he knows from Ma and TV. He doesn’t have the insight or maturity to connect the dots. Room leaves that up to the reader.

Since the novel is Jack’s story, the conceit makes the read challenging. But because Jack tells the story, the horror of Ma and Jack’s life is somehow tolerable. Jack does not have a handle on language and his sentences are incomplete and lacking. The author often drops Jack’s vernacular, which should be a problem, but is a welcomed relief.

At times, Room is very suspenseful. There is also humor as Jack tries to decrypt the new people and world around him. But having to wade through Jack’s private language and misunderstandings is often tedious.

Since a child narrates, there is not much philosophical or psychological debate about the impact of being held in a small, confining room. There is a moment when Jack observes a discussion on TV of what living one’s whole life in a small room might mean. Commentators draw comparisons of Jack’s life to Prometheus and Kasper Hauser.

Another brief idea is mentioned about prisoners – not only kidnapped victims but also convicted criminals – who are forced to spend their entire lives in solitary confinement. These ideas unfortunately go nowhere. There is no wider metaphor.

Room is about the horror of being kidnapped as a sex slave and the resulting consequences of having a child by your captor. Yet at its heart, Room is a love story between a mother and her child. In the end, it is love that saves them.

The film adaptation of Room is now a feature film.