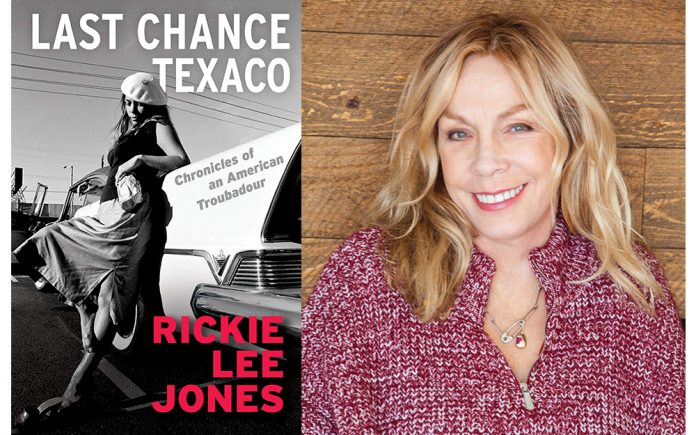

By Rickie Lee Jones (Grove Press)

By Eleni P. Austin

Back in 2009, Rock journalist Barney Hoskyns wrote “Low Side Of The Road,” fairly complete (but unauthorized) biography of Tom Waits. When he requested an interview with Rickie Lee Jones, she demurred, saying she was saving her stories for her own autobiography. I thought that is the book I want to read. Now that book is finally here.

In the Spring of 1979, Rickie Lee made a huge splash with the release of her self-titled debut album. Buoyed by the infectious single, “Chuck E.’s In Love,” it vaulted to the top of the charts landing at #3. It received five Grammy nominations and won one for Best New Artist. But this book chronicles everything that came before.

Born in late 1954, Rickie Lee was the third of four kids born to Richard and Bettye Jones. His dad had been a moderately successful vaudevillian known as Peg-Leg Jones. Both of her parents had been orphaned at various times in their childhoods. These painful experiences motivated her mom to want a stable marriage and family life. Meanwhile, her dreamy and musically talented dad nurtured showbiz ambitions, even as he drifted from one menial job to the next.

Rickie Lee endured a peripatetic childhood, moving back and forth from Chicago to Arizona to California to Washington. As a kid, she made her own fun, she pretended to be a horse, had an imaginary friend named Boshla and learned the rudiments of guitar and piano. As she got older, she wrangled horses for real, and her dad exposed her to Jazz and Broadway music. She promptly fell in love with the musical “West Side Story.” That obsession was supplanted in early 1964, when the Beatles made their historic debut on Ed Sullivan’s television show.

She grew up fast, physically and emotionally, her home life remained chaotic, the family was constantly on the move. Even when she made new friends, she lost them almost as quickly. For Rickie Lee, music became her safe place. She didn’t want to date the Beatles or Rolling Stones as much as be them. Music was an escape.

Just before her 11th birthday, her beloved older brother, Danny was involved in a devastating motorcycle accident that sent the family into a tailspin. He survived, but nothing was ever the same. Rickie Lee began to test her boundaries. Rebellion became a requirement for survival.

Not long after, Rickie Lee and her boyfriend, Ricci, stole a car and split town. Their destination was Los Angeles (‘Let’s go to L.A.’ I suggested, my cousin lives near the Sunset Strip. We can ask people, someone will know her”). Their gas tank got them as far as City Of Industry. She returned home, very much against her will. But after a few more escapes, her parents resigned themselves to her wanderlust.

Rickie Lee packed a lot of living into her first 20 years. On her own she crisscrossed the country, mostly hitchhiking, she made friends, aligned herself with kindred spirits and narrowly avoided disaster. Those experiences, as well as her parents’ histories, later informed her most enduring songs. By this time, she had discovered Laura Nyro, Van Morrison, Dr. John and had seen Jimi Hendrix live. Always in the back of her mind, her dream was to become a musician.

A bad boyfriend experience left her stranded in Chicago. A kindly police officer helped her out and they stayed in touch. It was also around this time she tried heroin. The feeling was overwhelming.

Finally, she landed in Venice Beach. It was there she crossed paths with pimps, musicians and drug dealers. She made lifelong friends like Mary Simon and Sal Bernardi. Unsung heroes like Mark Vaughan, Ivan Ulz and Alfred Johnson recognized her innate musicality.

One night, Ivan was playing at the Troubadour and invited Rickie Lee to crash his set. Chuck E. Weiss was working there and he quickly called his pal Tom Waits, insisting he had to hear to the girl onstage. After playing her own nascent composition, “Easy Money,” she followed up with a tender rendition of her dad’s song, “The Moon Is Made Of Gold.” In the middle of that song, “Almost on cue, I saw the kitchen door open and release a halo of light around the shadow of someone, someone watching me. Almost hiding. I felt him. I knew right away, it was Tom Waits’ scraggly shadow, formed by the kitchen’s light.”

Rickie Lee and Tom seemed perfectly matched. Each exhibited an affinity for all things vintage, from music to clothes to cars. But they danced around each other for a while, forming a tentative friendship.

Intent on pursuing a career in music, she cycled through a series of dullsville jobs, never quite understanding why she got fired. One office gig afforded a lot of down time, allowing her to work on lyrics for works-in-progress that would later evolve into “Chuck E.’s In Love,” “Youngblood” and “Coolsville. In the evenings, she would work out the melodies.

Whenever she was on the verge of giving up, her mother would encourage her to persevere. “She stood strong (she was always so strong!): ‘I know you feel bad right now, but don’t give up on your dream. Maybe you’ll be the one who succeeds. Don’t you quit now. Don’t give up without trying, Rickie.’ My mother. She was a mom from a long line of determined women who faced incredible adversity and was now reminding her daughter where she came from and where she was going. She kept me going when I wanted to set it all down. I guess it was the dark hour before the dawn. For even as I declared myself incapable, the threads of my life were braiding all around me.”

Not long after this crisis of confidence, she’d left Venice and had moved to a dismal flat in Beachwood Canyon, she and Tom Waits acted on their mutual attraction. He didn’t even have to give her the “baby, baby, don’t get hooked on me,” speech. Post-coital body language said it all. Lonelier than ever, Rickie Lee retreated.

Ivan Ulz stepped up again. He called Lowell George and began singing Rickie Lee’s praises and literally singing what lyrics he remembered from “Easy Money.” The Little Feat front-man was working on his solo debut. He included “Easy Money” on “Thanks, I’ll Eat It Here.” This was the break she needed. Soon enough, Lowell had taken her under his um wing, and she was traveling the streets of L.A. in style, riding shotgun in his Range Rover. (Sadly, he died before he got to see her career take off).

Her newly raised profile brought her to the attention of Warner Brothers Records president, Lenny Waronker. Rather quickly, she secured a publishing deal and signed with the artist-friendly label. Suddenly, Tom Waits was back in her orbit, and this time it felt like for keeps. A real Film Noir romance.

But Rickie Lee wasn’t finished flirting with danger, re-introduced to heroin, she began dabbling, secretly chasing the dragon, even as her wildest dreams were coming true and she was recording her self-titled debut.

Released in the Spring of 1979, her album garnered a bit of buzz. The label helped introduce her prodigious talents by creating a series of promotional videos. By utilizing the emerging marketing tool they began to reach a broader audience. The gamble paid off and she was invited to perform on “Saturday Night Live.”

Once again, her mettle was tested, when it became time to choose which two songs to sing. The effervescent first single, “Chuck E.’s In Love” was the obvious choice, but when the producers wanted the swingin’ “Danny’s All-Star Joint” to be the second number, she balked. She insisted the other song had to be her moody manifesto, “Coolsville.” Lines were drawn in the sand, but Rickie Lee was adamant. She triumphed and maintained her hard-won integrity.

Following her appearance on “SNL,” album sales exploded. Even though Disco and Punk were the musical lingua franca of the late ‘70s, critics and fans alike responded to her bohemian charms. Equal parts Jazzy chanteuse and intimate singer-songwriter, her songs were by turns intimate, buoyant and occasionally grandiloquent. Although short-sighted music writers tried to lump her in with Joni Mitchell (blonde women with guitars!), Rickie Lee was quick to point out her musical touchstones were Laura Nyro, Van Morrison, Broadway, Jazz and her dad. Her album peaked at #3.

Everything seemed to be coming together. She embarked on her first tour. Sold-out shows garnered rave reviews. She was featured on the cover of Rolling Stone. Superstar photographer, Annie Leibovitz shot the cover and announced “’You’re the sexiest person I have ever photographed next to Mick Jagger.’” Rickie Lee remembers thinking at the time, “I am way sexier than Mick Jagger.” Meanwhile, Time magazine dubbed her “The Duchess Of Coolsville.” By now she was actually cohabitating with Tom Waits. Even so, it still felt like one step forward and two steps back.

As her fame began to eclipse Tom’s, he grew more possessive, almost expecting to take on a traditional housewife role. But when she confessed her heroin habit (“If he loves me than I can tell him,” she thinks. “I think I can tell him. I need to tell him. Now. About the dope”), he practically broke up with her. Ultimately, she decided she didn’t want her fame to “tarnish his cool crown” and they’re done. Devastated, she wrote the heartbreaking “Skeletons” song. Retreating to her mom’s house in Olympia, Washington, she begins work on what would become her magnificent sophomore record, Pirates.

After winning a Grammy for Best New Artist, Rickie Lee relocated to New York City where she began a romantic relationship with her pal, Sal Bernardi, kicked heroin and completed Pirates, which arrived in 1981.

She sums up the ensuing 40 years in about 25 pages, which is disappointing. But hopefully means she’ll start working on a volume two that will delve deeper into marriage, motherhood, divorce and the inspiration behind brilliant albums like Flying Cowboys, Traffic From Paradise, Evening Of My Best Day and The Other Side Of Desire. As well as life on the road, love, loss and the vagaries of the music business.

Rickie Lee writes exactly as you hope she would. She’s sharp and honest, she displays a quick wit and a mordant sense of humor. Her prose is matter-of-fact and deeply intimate. There’s a specificity to her language that matches the vivid imagery found in her songs. She tells her stories and shares her secrets and it feels as though she’s speaking only to you. It’s equal parts confessional and conversational.

Mostly, it makes you want to listen to her music non-stop. I’m listening to it right now. Full confession, Rickie Lee Jones has had me under her spell since I saw her perform on “SNL” a few weeks before my 16th birthday. It was the music I’d been waiting for all my life, I just didn’t know it. I forgot her name, but luckily, I saw a huge poster in the window of Licorice Pizza and promptly bought the cassette. I was instantly transported by the finger-poppin’ cool, moments of bravado mixed with vulnerability. I felt like it mirrored my own moments of arrogance and fragility. I couldn’t get enough, I still can’t.

Okay, I gotta go, The Last Chance Texaco is coming on. It’s perfect that it’s also the name of her book. Automotive metaphors like “Well, he tried to be Standard, he tried to be Mobil, he tried living in a World and in a Shell/There was a block-busted blonde, he loved her-free parts labor, but she broke down and died, and threw all the rods that he gave her,” are deft and economical. The instrumentation is spare, but the arrangement is expansive, and somehow makes it seem like Big Rig trucks are whizzing past you on a desolate and lonely highway. Her book has that same verisimilitude. I almost want to re-read it right now, it’s that good.