By Eleni P. Austin

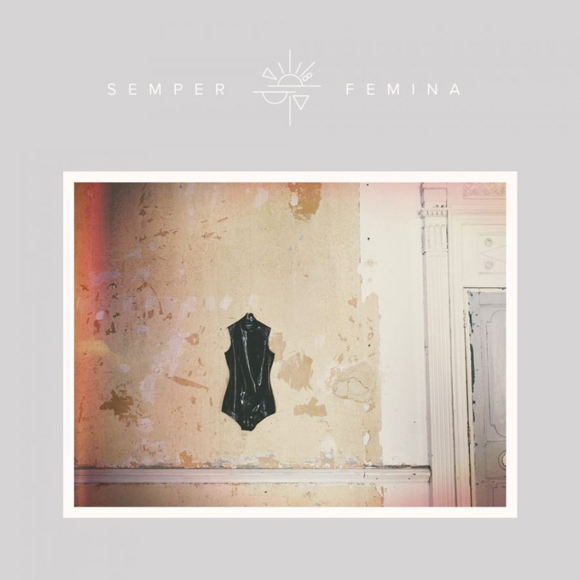

“We’ve not got long you know, to bask in the afterglow/Once it’s gone it’s gone, Love waits for no one.” That’s Laura Marling sharing some hard won wisdom on her newest album Semper Femina.

Laura Marling grew up in Hampshire, England, the youngest of three daughters. Born in 1990, she was raised on a farm near Workingham. Despite a pedigreed background, her father, Charlie, (officially Charles William Somerset Marling, 5th Baronet), ran a small recording studio on the property.

A lot of bands recorded there, most notably the La’s and Black Sabbath, Laura’s childhood was dominated by music. By age six, she had mastered the chord changes for Neil Young’s “The Needle and The Damage Done.” For her 13th birthday her parents gave her two records; Blue by Joni Mitchell and Horses from Patti Smith. After that, there was no turning back.

In 2006, she moved to London, she was just 16, but determined to have a career in music. The UK was experiencing a Folkie renaissance and Laura fell in with like-minded players. She was part of Noah & The Whale’s original line-up but quickly opted to go solo. Soon she was sharing stages with up-and-comers like Jamie T. and Adele.

By age 18, she released her debut, Alas I Cannot Swim. Produced by Noah & The Whale front man (and ex-beau), Charlie Fink, it was immediately embraced by critics, and fans alike. Within the space of six months she moved up from opening act to headlining 3,000 seat venues. Critics were calling her the next Joni Mitchell and she began a whirlwind romance with the drummer of her touring band, Marcus Mumford. Alas… was nominated for a prestigious Mercury Music Prize.

Rather than rest on her laurels, she returned to the studio and 2010 saw the release of her sophomore effort, I Speak Because I Can, produced by Ethan Johns. The album exhibited a sense of depth and maturity that belied her tender age. Ethan, son of legendary producer Glyn, (Rolling Stones, Led Zeppelin, the Who), had made his bones producing everyone from Ryan Adams and Kings Of Leon to the Jayhawks and Rufus Wainwright. Thus, a creative partnership was born, he was behind the boards for her third record, 2011’s Creature I Don’t Know, and stuck around for her watershed album, Once I Was An Eagle.

Arriving in 2013, Once… was a revelation. The music drew inspiration from disparate sources like Joni Mitchell, Led Zeppelin, Fairport Convention and Kate Bush. The lyrics confidently parsed the agony of heartbreak, the regenerative power of solitude and the frisson of new romance.

Laura relocated to Los Angeles and her next effort, 2015’s Short Movie, took a sharp left turn. She produced the record herself, incorporating electric instrumentation, and adopting a more aggressive singing style. She succeeded in not repeating herself, but she alienated fans who were hoping for Once I Was An Eagle 2, Electric Boogaloo. Although it sold well, and received solid notices, ultimately it felt unsatisfying.

Now she has returned with her sixth album, Semper Femina. The title is nicked from an ancient poem from Virgil. Roughly translated from Latin it means “woman is ever a fickle and changeable thing.” This time out Laura enlisted producer Blake Mills.

Now she has returned with her sixth album, Semper Femina. The title is nicked from an ancient poem from Virgil. Roughly translated from Latin it means “woman is ever a fickle and changeable thing.” This time out Laura enlisted producer Blake Mills.

Barely 30, Blake, like Ethan Johns is a musician and a producer. The Los Angeles native cut his teeth making music as a teen in his own band, Simon Dawes, then spent several years working as a session musician. He has toured and/or recorded with Avett Brothers, Jenny Lewis, Band Of Horses, Dangermouse, Conor Oberst, Norah Jones and Lucinda Williams. He also released two solo albums in 2010 and 2014.

The opening cut, “Soothing,” feels chilly and remote. Powered by a clunky beat, bowed bass lines, whispery guitar and strings that seem zither-y one minute and harpsichord-y the next. Broody, brittle and dense, it leans closer to quiescent Electronica than rustic Folk. Laura’s mien is arch and seductive one minute; “I need some soothing…” caustic and dismissive the next; “Oh my hopeless wanderer, you can’t come in, you don’t live here anymore.”

Laura has said in interviews that this record represents a “masculine time in her life,” she even tattooed the Virgil quote on her leg. So it seems like less of a coincidence that each track in this nine song cycle addresses or concerns a woman.

Four songs seem to indicate an infatuation or romance gone awry. “Wild Fire” is anchored by nickering percussion, see-saw guitar and warm electric piano notes. She adopts a sanguine singing style that hews closely to Dusty Springfield’s blue-eyed soul. Her countenance is by turns playful, wanton and pissed off. The stream-of-conscious lyrics flow like an intimate conversation; “You always say you love me most when I don’t know I’m being seen, Well maybe someday when god takes me away I’ll understand what the fuck that means/I just know your mama’s kind of sad, and your daddy’s kind of mean, I could take it all away, you can stop playing that shit out on me.”

“Always This Way” is less confrontational. Rumbling upright bass and a thumpy backbeat connect with sun dappled guitar and sawing violin. Fluttery arpeggios on the instrumental break belie lyrics that are suffused in sadness and resignation; “Now she’s gone and I’m all alone, and she will not be replaced/Stare at the phone try to carry on, but I have made my mistake.”

Searching electric guitar chords gather around a slip-stitch rhythm on the searing “Don’t Pass Me By.” Feathery strings and sleigh bell accents are folded into the arrangement, cryptic lyrics seem to confront an infidelity; “Is it something you make a habit of? That’s not what I need from love right now.”

Finally, “Nouel” is a fairly direct paean to another woman. The most bare-bones track on the album, it’s just Laura’s trilling vocals and fleet and filigreed acoustic fretwork. “Nouel” clearly embodies Virgil’s idee fixe on femininity, and nothing about this intimate portrait feels platonic; “She lays herself across the bed, like the Origin Du Monde/Slight of shoulder, long in leg, and her hair a faded blonde.”

Other interesting tracks include “The Valley,” hushed and bucolic, Laura’s vocals are layered over plangent acoustic guitars and sparkling strings. Wistful and melancholy lyrics pay homage to an enigmatic beauty, who feels just out of reach. “Wild Once” is spare and plaintive. Meanwhile, “Next Time” is a shivery roundelay that weds galumphing kerplunk percussion to twinkly keys, shimmery guitar and swooping strings. The lyrics vow to “do better next time.”

The album closes with “Nothing Not Nearly.” Woozy electric guitar wraps around cascading acoustic arpeggios and a clanking, metallic beat. She spits verses of regret with a Dylanesque cynicism but her sweet soprano cloaks the carpe diem chorus, she’s bloodied but unbowed; “The only thing I learnt in a year, where I didn’t smile once, not really/Is nothing matters more than love, no nothing, no not nothing not nearly.” The song’s sprightly acoustic instrumental coda signifies light at the end of a very long tunnel.

While Laura sang and played guitar, Blake Mills also played guitar, and they were ably assisted by drummers Matt Ingram and Matt Chamberlain, bassists Nick Pill and Sebastian Steinberg, and Pete Randall on guitar. Rob Moose arranged and played all the strings.

Semper Femina doesn’t scale the heights of Once I Was An Eagle, but it comes pretty goddamn close. Laura’s music remains honest and authentic. It echoes antecedents like Joni Mitchell and Kate Bush, without ever feeling derivative. She offers an enigmatic self- portrait that’s shaded with nuance and heartbreak. It feels as though she’s crammed a lifetime of experience into 26 years. The truth is, Laura Marling is just getting started.