By Eleni P. Austin

“Hey You! Don’t watch that, watch this/This is the heavy, heavy monster sound, the nuttiest sound around…”

If you came of age in the late ‘70s and early ‘80s, well, shit, you’re old. But you are probably thoroughly familiar with the lyrics quoted above and are currently repeating the rest in your head.

Undoubtedly for you, that era feels like it happened five minutes ago. A more optimistic time, Punk Rock morphed into the more homogenized New Wave. Dayglo colors were de riguer, shirt collars were popped, Bermuda shorts were in and MTV was just beginning world domination.

For most Suburban teens, MTV exposed them to music they never would have heard on their local Top 40 stations. Some of the acts they broke continue to remain relevant today, (U2, Prince, Peter Gabriel, Madonna), some reigned supreme and were quickly forgotten (Kajagoogoo, Quiet Riot, Michael Sembello). But there are some songs that remain iconic. Duran, Duran’s “Hungry Like The Wolf,” Wall Of Voodoo’s “Mexican Radio,” Thomas Dolby’s “She Blinded Me With Science,” and “Our House” from Madness.

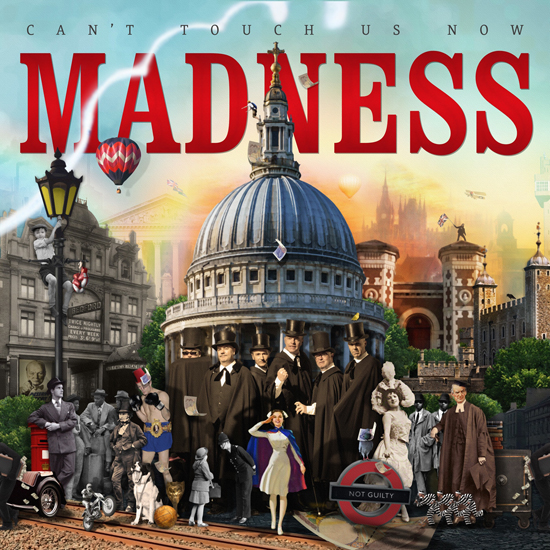

Madness, along with English Beat, the Specials, and The Selecter, first spearheaded the 2Tone sound. A fusion of Jamaican Ska, Reggae and Punk Rock, the music was socially conscious and extremely danceable. The band broke through in America but remain massively popular in Great Britain.

The core of the band, guitarist Chris Forman, Mike Barson on vocals and keys and Lee Thompson on saxophone and vocals formed over 40 years ago in Camden Town, London as the North London Invaders. The trio recruited Cathal Smyth (ne’ Chas Smash) on trumpet and acoustic guitar, Graham “Suggs” McPherson on lead vocals, drummer Daniel Woodgate and bassist Mark Bedford They briefly became the Morris Minors, before settling on Madness, after a favorite song from Ska pioneer Prince Buster.

By 1979 they had attracted a large local following, gigging around Camden Town. They recorded their first single, “The Prince,” as an homage to Prince Buster. The song was released on the 2Tone label and the seven-piece toured with other 2Tone artists, the Speicals and the Selecter. Their song was a surprise hit, peaking at #16 on the U.K. charts. Madness gained further exposure with a performance on the BBC series, “Top Of The Pops.” Soon after, they signed a deal with Stiff Records, home to Nick Lowe, the Damned and Elvis Costello.

Their debut, One Step Beyond, arrived in October and featured two Prince Buster covers, the title track, and of course, “Madness,” plus a surfeit of originals that strayed from the Ska-Punk paradigm, incorporating Motown, Pop, Northern Soul and English Music Hall music into their sound. Equally compelling was the septet’s anarchic sense of humor. The band’s sheer nuttiness propelled them to #2 on the UK charts.

Madness hit the same chart position a year later with their sophomore release, Absolutely. Propelled by hit singles like “Baggy Trousers” and “Embarrassment,” even the instrumental “The Return Of The Las Palmas Seven” climbed to number seven on the singles chart. Their third effort, 7, cemented their position, along with the Jam, as England’s biggest hit-makers. In America, a couple of songs from their debut had received airplay on MTV, but their goal was world domination.

For their fourth album, The Rise & Fall, Madness continued to collaborate with producers Clive Langer and Alan Winstanley, the duo had been with them since the beginning. Released in 1982, Rise… was something of a concept album about nostalgia and childhood; it also contained some astute social commentary.

This time out they integrated hints of Jazz and Middle Eastern influences. But the album’s secret weapon was “Our House,” an irresistible slice of life, it’s exuberant style a mash up of Ska and traditional Music Hall. The lyrics, a clever, slightly smart-ass trip down memory lane, laced with humor and pathos in equal doses.

The song made it to #5 in the UK and #7 in the U.S. Geffen, Madness’ American label capitalized on the single’s popularity by releasing a self-titled compilation that cherry-picked tracks from all four British LPs. The strategy worked, the album cracked the Top 200 and introduced their music to a wider audience.

The band released two more albums with the original line-up, Keep Moving in 1984, Mad Not Mad in 1985. Mike Barson quit the band in the midst of the Keep Moving recording sessions. He returned in 1986 for a farewell single and tour. After the band officially broke up, some members soldiered on as The Madness and recorded an eponymous effort in 1988.

In 1992 the band was persuaded to reunite when a greatest hits collection topped the charts. They would reconvene sporadically throughout the ‘90s, finally they recorded their eighth album, Wonderful. Released at the turn of the 20th century, it reached #17 on the U.K. charts, a respectable showing for a band that had their first hit 20 years before.

The low-key Dangerman Sessions arrived in 2005 and four years later their 10th studio album, The Liberty Of Norton Fulgate was released to coincide with the 30th anniversary of their 1979 debut. Their 2012 record, Oui Oui, Si Si, Ja Ja, Da Da preceded two major milestones for Great Britain: the Queen’s Diamond Jubilee and the 2012 London Olympics. Madness was invited to perform at both events. It was a bit of a Victory lap for the band, but rather than rest on their laurels, they’ve returned with Can’t Touch Us Now.

The title track gets the record off to a rousing start as bee-stung guitar riffs layer over plinky piano, insistent sax notes and a stutter-step rhythm. The melody is a heady brew of Northern Soul and Music Hall that ebbs and flows. Initially, the lyrics seem fairly straightforward, presenting two lovers at the precipice of commitment. But dig a little deeper and they feel like a metaphor for religious or political conviction. The instrumentation veers from sweet to fractious, emphasizing the song’s duality.

The title track gets the record off to a rousing start as bee-stung guitar riffs layer over plinky piano, insistent sax notes and a stutter-step rhythm. The melody is a heady brew of Northern Soul and Music Hall that ebbs and flows. Initially, the lyrics seem fairly straightforward, presenting two lovers at the precipice of commitment. But dig a little deeper and they feel like a metaphor for religious or political conviction. The instrumentation veers from sweet to fractious, emphasizing the song’s duality.

After 40 years, this band really has nothing to prove. So it’s kind of wonderful to report that this is probably their most concise and cohesive collection of songs to date. Several tracks offer up their trademark of barbed social commentary and danceable grooves.

The soulful shimmy of “Good Times” is propelled by sinewy sax and swiveling rhythms that belie stern lyrics which preach asceticism over rampant consumerism. Social hypocrisy is on trial on the exuberant “Mr. Apples.” Anchored by knockabout percussion, jaunty piano runs and brass that honks and wails, the lyrics paint a vivid portrait of a well-respected man; “Head of the table at the Rotary Club, never unsure of which shoulders to rub/Scout leader, a pillar of the church, capital punishment he wants to bring back the birch.” But at night it’s another story, the lyrics reveal cavorts with ladies of the evening. A stinging guitar solo underscores his rank duplicity.

Politics and religion are the targets on “Mumbo Jumbo” and “I Believe.” Over an fun-house melody that boings and pulsates, incorporating bloopy organ notes, jews-harp, trombone, banjo and hopscotch back-beat, the former seems ripped from the headlines.

Not only do the lyrics denounce Brexit; “You propagate the notion that pigs will fly, social services stretched to a pie in the sky,” they also cleverly hint at the return of Thatcherism; “stoke a little fear back down on Maggie’s Farm.” They even take a moment to excoriate Donald Trump; “You promised us a pudding but never the proof, a cathedral of deceit to sodomize the truth/The masses are rejecting and showing you the door, their peaceful demonstration is past the point to ignore.”

The latter blends call-and-response vocals and rippling Reggae Riddims that nearly camouflage a trenchant commentary on organized religion. The rollicking combo of piano, Wurlitzer and harpsichord leavens this withering critique; “I decide whom I confide, and you just failed the test/Release your hands from my beliefs, I no longer need your guiding.”

Much like the Kinks, Madness songs have always exhibited a keen observational style. That tradition continues on songs like “Blackbird,” “Pam The Hawk,” and “You Are My Everything,” each one unspools like a short story.

On “Blackbird” ambient traffic noise and rain is supplanted by Suggs’ spoken-word intro as he vividly describes a case of instant attraction. “She’s striding through puddles, on black stiletto heels, guitar over one shoulder/Swirling swagger in her stride, and a well-appointed pencil skirt maybe 18 inches wide.” The melody and instrumentation is initially Mersey-Beat smooth, but quickly accelerates as attraction piques. Soon a mellotron, brass and a Gospel choir all chime in.

The bellicose noise of slot machines and jingling change greet the listener on the bleak “Pam The Hawk.” A brittle tale of a streetwalker who gambles away her profits on games of chance. “She’d be the richest woman in all of the West End they’d say, if every single penny earned she didn’t spend in the bookies, on the horses, the Wardour Street arcade/There isn’t a single fruit machine she hasn’t played.” A dour little torch song her tale of woe is accentuated by a mournful sax solo, Jazzy acoustic guitar and a sweeping horn section.

Finally, “You Are My Everything” is Superfly perfection. Wah-wah guitars snake through shaker percussion, tinkling glockenspiel and a string section in a seductive arrangement that would make Isaac Hayes, Curtis Mayfield and Barry White collectively weep. The lyrics spin a series of scenarios that pledge undying love. “If there ever comes a day if you walk out the door and leave it all behind, I won’t hold back and try to make you stay/I know I said I don’t mind, in truth I’d rather go blind, you are my everything.”

On an album that feels front-loaded with hits, three songs stand out from the pack. The melody of “Another Version Of Me” feels like a relax-fit sequel to “Our House.” Spiralling piano notes collide with blustery sax and a slinky backbeat. The lyrics limn the foibles of family life without ever breaking a sweat.

“Grand Slam” is a Spaghetti Western/Reggae pastiche that blends bongo-riffic rhythms, space-age synths, syncopated brass and plonky piano. The lyrics take aim at a self-satisfied alpha-male; “Grand slam, is he the man? Relentless turbo-charged homo sapien.” It’s never made explicit, but the specimen in question probably has small hands, stubby fingers and an orange comb-over.

Finally, “Herbert” is quintessential Madness. A fizzy synthesis of Ska and Music Hall, it’s by turns, convivial, risqué and wildly irresistible. Over Carnival keys, a clickity-clack rhythm and kaleidoscopic horns, Suggs unravels a shaggy dog shagging story involving covert coitus in a bathroom stall.

Other interesting tracks include the urgent life-lessons of “Don’t Leave The Past Behind,” the skanking cynicism of “Given The Opportunity,” the percolating soulshine of “(Don’t Let Them) Catch You Crying,” and the querulous Funk of “Soul Denying.” The album closes with the see-saw jabberwocky of “Whistle In The Dark.”

In a nice bit of symmetry, the album is co-produced by Clive Langer, along with Liam Watson, Charlie Andrew and the band. Langer was on hand for their debut, and has handled production chores for eight other Madness records.

Despite the fact that the members of Madness are all nearly eligible for the British equivalent Social Security, they still manage to keep their Ska-Punk formula feeling fresh. To paraphrase the Pretenders, they’ve got rhythm, can’t miss a beat, got new skank, so reet. Sure, the ‘80s are long gone, MTV is home to reality television, and your pastel Bermuda shorts are probably too tight around the waist. But thankfully, Madness is here to stay.