By Eleni P. Austin

1982 was an interesting year for Pop music. It felt like anything was possible. Proven hit-makers like Stevie Wonder, J. Geils and Journey were in the Top 40. So were crap-tastic tracks by Air Supply, Quarteflash and Charlene, (remember the execrable “I’ve Never Been To Me?”) But the top of the charts belonged to relative newcomers like Joan Jett, the Go-Go’s and Huey Lewis & The News.

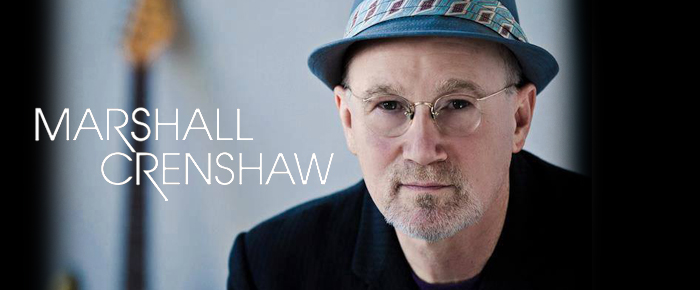

It was rather serendipitous that Marshall Crenshaw’s full-length, eponymous debut was released in the Spring of 1982. The day-glo colors of the album cover hinted at a New Wave sensibility. But the picture of a bespectacled Crenshaw looked like a retro combination of Buddy Holly and John Lennon. The whole package seemed intriguing. The music exceeded expectations.

Crenshaw had been working toward his debut since picking up a guitar at age 10. Marshall Crenshaw was born in Detroit in 1953, but grew up in the nearby suburb of Berkley. Throughout high school he played in a series of bands. Following graduation he fronted a band called Astigafa, (an acronym for “a splendid time is guaranteed for all,” a lyric found in the Beatles’ “Being For The Benefit Of Mr. Kite”).

By 1973, Crenshaw had completely lost interest in listening to Pop radio; he found it narrow and somewhat whitewashed. Instead, he concentrated on ‘45s released in the ‘50s and ‘60s. While he was totally entranced by the echo-y slap-back sound of primitive Rock & Roll, he was equally infatuated by the romantic Soul music that saturated the R&B radio stations. Each style informed his songwriting.

Detroit lost a bit of its musical cache once the Motown label had relocated to the West Coast in the early ‘70s. By the end of the decade, there wasn’t much of a scene. With his nascent career at a standstill, Crenshaw was searching for new opportunities. After answering an ad in Rolling Stone. He was cast in the Broadway production, “Beatlemania.”

Winning the role of John Lennon, he endured several months of “Beatle Boot Camp” before the show premiered. A run in San Francisco and Hollywood was followed by six months in the road company. After a while, performing songs made famous by other musicians felt like the equivalent of artistic asphyxiation, but Crenshaw finished the experience knowing exactly what kind of music he wanted to make. He bought a four-track recorder and began honing his own compositions.

Armed with a plethora of demos, Crenshaw relocated to New York City. He recruited younger brother, Robert, to play drums, and auditioned about 30 bass players, before settling on Chris Donato. He actually spent time walking the city, dropping demo tapes to various show business movers and shakers.

Journalist/Record label president Alan Betrock was a recipient of a demo cassette. Another found its way into the hands of Rockabilly revivalist Robert Gordon. Both became early and ardent supporters of Marshall Crenshaw’s protean talent. Gordon ended up recording a song, “Someday, Someway” on his 1981 album, Are You Gonna Be The One.

Betrock went one step further and released Crenshaw’s first single, “Something’s Gonna Happen” on his Shake record label. The song created enough of a buzz that major labels came a’ callin’

and he signed a deal with Warner Brothers. Initially, Crenshaw attempted to produce the album himself but became bogged down by the minutiae of the recording process. The label suggested he get a producer. They settled on Richard Gotthrer, whom Crenshaw met at a Robert Gordon session.

Richard Gottehrer got his start at the infamous Brill Building back in the early ‘60s. By the ‘80s he had produced everyone from the Strangeloves (the original version of his “I Want Candy” composition), to David Bowie, Blondie, Richard Hell & The Void-oids and the Go-Go’s. Released in late 1981, the Go-Go’s debut, Beauty And The Beat, stayed at #1 for six weeks. It was the first “girl group” album to accomplish that feat.

Gottehrer streamlined Crenshaw’s sound. When his self-titled debut arrived in the Spring of 1982, it felt like a breath of fresh air. The songs were catchy and concise; there were hints of Rockabilly, Power Pop and even a soupcon of stripped-down Country Western. The first single, “Someday, Someway” made it into the Top 40, and the album spent six months in the Billboard Hot 100 chart, peaking at #50.

Crenshaw followed up with a string of excellent albums in the ‘80s; “Field Day,” “Downtown,” “Mary Jean & 9 Others” and “Good Evening.” Although they didn’t rocket up the charts, they received critical acclaim and he consistently maintained a loyal and enthusiastic fan base.

By the ‘90s, Crenshaw was still making music, he released three studio albums, Life’s Too Short, Miracle Of Science and #447, plus a live recording, Live…My Truck Is My Home. He also began acting in movies like “Peggy Sue Got Married” and “La Bamba.” In the latter he portrayed his doppelganger, Buddy Holly. He also made appearances on Nickelodeon’s cult classic series, “The Adventures Of Pete & Pete.”

Somehow he found time to produce a compilation for Capitol Records called Hillbilly Music…Thank God,Vol.1 and published a book, Hollywood Rock: A Guide To Rock n Roll In The Movies. Along the way, female vocalists like Lou Ann Barton, Bette Midler, Marti Jones, Kelly Willis and Ronnie Spector began covering his songs. He co-wrote “Til’ I Hear It From You” with members of the Gin Blossoms, the song went to #4 on the Billboard Hot 100.

In the 21st century, Crenshaw has only released two records, What’s In The Bag and Jaggedland. He co-wrote a song for the “Walk The Line” parody film, “Walk Hard,” he also began hosting his own radio program, “Bottomless Pit” on WFUV.

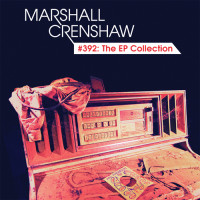

Noting the resurgence of vinyl, he decided to forgo recording a full-length album and just release a series of 10” vinyl EPs. Since 2012, he has sporadically self-released a total of six EPs. Each consist of a new song, a cover and a reconfiguration of a Marshall Crenshaw classic. The new songs and covers have just been collected in CD form and issued as his 11th studio album entitled #392: The EP Collection.

The first six songs here are new Crenshaw originals that are so perspicacious they manage the neat trick of feeling familiar and contemporary at the same time. Both “Grab This Train,” which opens the record, and “Driving And Dreaming” offer travel as a sort of emotional panacea.

The former is anchored by a shuffle rhythm and strumming acoustic arpeggios. Pining for a lost love, he opts for a train trip as a way to travel back in time. The leisurely ride on the rails allows him to “lose myself in sweet memories of the past.” But even as he reaches his destination, he realizes he can’t out run his troubles. “So now I’m here, but it seems to be, that I tried to run but the blues came and found me/Found me here, on memory lane, so it’s back the way I came to grab the next train.”

The latter is powered by an off-kilter hiccup-y beat, a Hammond B3 wash and liquid guitar licks that echo and sway. A lengthy road trip gives Crenshaw time to ruminate about past mistakes and lost opportunities. He has an epiphany, but it gets lost as the landscape rushes by. He’s “fighting a losing battle with the Oklahoma wind/The joy’s gone out of joyride, and I’m still nowhere, Here I am still nowhere/Nowhere near the end.”

With “Move Now” and “Red Wine” He adds new colors to his sonic palette. “Move…” is built around ringing rhythm guitar chords and an urgent Cha-Cha-Cha tempo. Crenshaw plays all the instruments himself and his lead guitar licks spiral and saw, underscoring the lyrics’ incipient paranoia; “Don’t wait until they come, with their licorice gum…their bourbon and rum, their oxycontin guns.”

“Red Wine” is a little more mellow and contemplative. Lilting accordion runs gives the melody a Parisian patina. In the midst of a romantic crisis, drinking steadies his nerves and gives him some perspective. “…It still holds true, with everything we’ve been through, it’s still you/ I’m still in the game sitting here with you on my mind.” Crenshaw rips a silver-tongued guitar solo that’s as eloquent as his lyrics.

“Stranger And Stranger” tackles themes of love and loss inspired by the death of his father and the Sandy Hook school tragedy that followed. He ruefully notes that “time can be a cruel re-arranger.” The propulsive tune, anchored by bongos, conga and vibraphone, nearly camouflage the song’s dire mood. Once again, Crenshaw delivers a stunning guitar solo, tensile and razor sharp.

“I Don’t See You Laughing Now” closes out the set of original songs. A loping melody is tethered to a galloping gait. The lyrics offer a stinging rebuke to a morally bankrupt dickhead finally receiving comeuppance.

Half of this album is cover songs. In lesser hands, this might seem like a lazy dodge. But Marshall Crenshaw has such an encyclopedic knowledge of Pop music that only the most canny listener will recognize most of these tracks.

The songs that receive the most faithful renderings are the Carpenters’ “Close To You” and The Move’s “No Time.” “Close To You” is super corny and somewhat treacly but so what. Written by Burt Bacharach and Hal David, it’s a classic that every Baby Boomer instinctively swoons to. Crenshaw’s rendition is lush and ethereal, the arrangement even includes Bacharach’s trademark flatulent trumpet filigrees.

The Move was Jeff Lynne’s pre-ELO band, “No Time” was never a huge hit, but it’s an intriguing slice of Elizabethan Brit-Pop powered by a trilling mellotron and vague doomsday lyrics.

The Bobby Fuller Four was a U.S. band that seemed inspired by Buddy Holly and the Beatles in equal measure. Crenshaw’s cover of their “Never To Be Forgotten” jettison’s the original’s Wall Of Sound production. Instead, it hits a sweet spot between Roots Rock jangle and British Invasion harmonies.

Crenshaw takes a pass at singer-songwriter James McMurtry’s “Right Here Now.” Stripping away the track’s defiant mien and then adding layers of sitar-riffic guitar. Meanwhile, in his hands, the Lovin’ Spoonful’s “Didn’t Want To Have To Do It” is recast as an extravagantly soulful ballad. It hews closely to the sound pioneered in the early ‘70s by Philadelphia International Records.

Other interesting tracks include a live take of the Everly Brothers’ “Man With Money” and a rollicking version of “Made My Bed, Gonna Lie In It” from Aussie Garage Rockers, The Easybeats.

The album closes with a demo of an unreleased original, “Front Page News.” This is a demo in name only. Crisp and economical, its stripped-down sound echoes the early Rock & Roll pioneered by Buddy Holly, Elvis Presley and Ricky Nelson.

Despite the fact that these songs were recorded piecemeal, over the course of three years, it’s a very cohesive album. Several of the songs on “#392” were co-written with Dan Bern, a fine singer-songwriter in his own right.

It seems as though Marshall Crenshaw has been around forever. But his music never feels dated. In an era of autotunes and twerk-ery, it’s nice to know that real talent never goes out of style.