By Eleni P. Austin

Growing up in Berkley, Michigan, a suburb outside of Detroit, Marshall Crenshaw became obsessed with music at an early age. By the fifth grade, he was playing guitar. A couple years later, he was fronting his own bands. By the early ‘70s, he felt the local music scene was stagnating, so he signed on with the touring company of Beatlemania, winning the role of John Lennon. Limited runs in San Francisco and Hollywood were followed by shows that played across the country. By the end of his tenure, he knew exactly how he wanted his own music to sound. He purchased a four-track recorder and hunkered down, honing his own songs.

Having spent his adolescence collecting ‘45s released in the ‘50s and ‘60s, he knew instinctively that the sound he was going for would incorporate the echo-y slap-back of primitive Rock & Roll, catchy Soul and romantic R&B that was a Motown specialty. By the time he moved to New York City, he was armed with an arsenal of killer songs. He recruited his brother Robert to play drums, and after an arduous search, found bassist Chris Donato. The trio recorded a demo. He then walked the city, dropping off demo tapes with various showbiz movers and shakers. His diligence paid off. First, he connected with Alan Betrock who became an indefatigable champion, soon enough, he inked a deal with Warner Brothers Records.

Initially, Marshall wanted to produce the album himself, but realized rather quickly that he couldn’t get out of his own way. So, the label brought in veteran producer Richard Gottherer who had recently helmed The Go-Go’s debut, Beauty And The Beat, which would go on to climb the charts, spending six weeks at #1. The L.A. all-female five-piece, whose sound fused Punk and Pop, were the first “Girl Group” to achieve that feat.

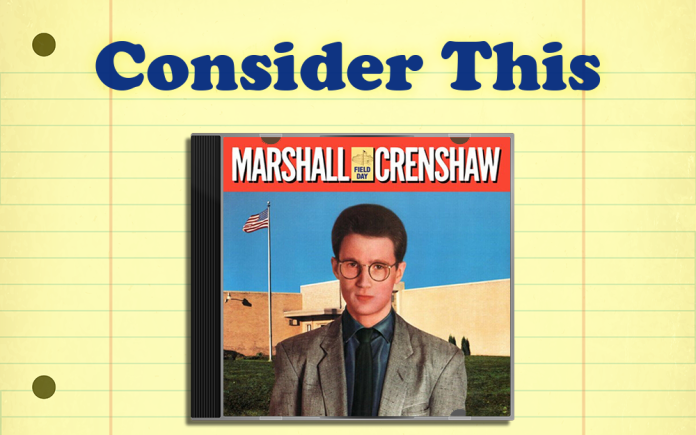

When Marshall’s self-titled debut arrived a few months later in the Spring of 1982, it was a breath of fresh air. Critics were effusive, comparing him to other bespectacled musical innovators like Buddy Holly, John Lennon and Elvis Costello. His songs were catchy and concise, whipping up a frothy cocktail of Rockabilly, Rock, Power Pop, stripped-down C&W and a soupcon of Soulful R&B. The first single, “Someday, Someway,” made it’s way into the Top 40, sharing that rarified air with proven hit-makers like Stevie Wonder, J. Geils Band and Journey, along with crap-tastic acts like Air Supply, Quarterflash and Charlene (who could forget her execrable “I’ve Never Been To Me?”) and new kids on the block like Huey Lewis, Joan Jett and The Go-Go’s.

Since those heady, Day-Glo days, Marshall has continued to write, record and tour releasing ten more solo albums; Field Day, Downtown, Mary Jane & 9 Others and Good Evening in the ‘80s. Life’s Too Short, Miracle Of Science, and #447 in the ‘90s. The 21st century brought What’s In The Bag, Jaggedland and #392, The EP Collection. There have also been a few live sets and myriad compilations. He has also ventured into other areas of the entertainment industry. The Buddy Holly comparisons were magnified when he played the late Texas Rock legend in the 1987 Richie Valens biopic, La Bamba. He also landed acting gigs in Francis Ford Coppola’s Peggy Sue Got Married and the quirky Nickelodeon TV series, The Adventures Of Pete & Pete. Somehow, he found time to produce a compilation for Capitol Records called Hillbilly Music….Thank God, Vol. 1 and published a book, Hollywood Rock: A Guide To Rock N’ Roll In The Movies. Long recognized for his crackling songcraft, everyone from Lou Ann Barton, Ronnie Spector and Bette Midler have covered his songs. He also co-wrote the Gin Blossoms’ Top 10 ‘90s hit, “Til I Hear It From You,” and co-wrote music for the hilarious Walk The Line parody film, Walk Hard. These days, when he isn’t on the road performing his own hits, he occasionally tours with the surviving members of The Smithereens, filling in for late front-man Pat DiNizio. The last couple of years, he has partnered with the cool, kids at Yep Roc records to remaster and reissue his original Warner Brothers albums, which were released between 1982 and 1989. 2022 saw the 40th anniversary edition of his self-titled debut, now his sophomore effort, Field Day, has hit that same milestone.

The album opens with the one-two punch of “Whenever You’re On My Mind” and “Our Town.” both songs find our hero, to paraphrase Rodgers & Hart, bewitched, bothered and bewildered by love. “Whenever…” also doubled as the album’s first single, an iridescent slice of shimmery Power Pop, it’s anchored by jaggy guitars, lithe bass lines and a walloping beat. Marshall’s boyish tenor wraps around lyrics that perfectly portray that thunderstruck feeling that accompanies young love; “I think about you and forget what I’ve tried to be, everything is foggy and hard to see….I think about you and I’m weak, though I’m in my prime, set my watch and still lose track of time, it seems to be, but can it be, a fantasy?” Despite feeling besotted and befuddled, he still manages to uncoil a serpentine guitar solo that snakes through the break, leading to this final epiphany; “I never thought I’d be in this situation, it seems wherever I go, I’m with you, and though I never seem to find my place, at every turn, I see your face.”

Before the opener’s final refrain has receded, “Our Town” simply leaps out of the speakers, chunky power chords are tethered to thrumming bass lines, twinkly glockenspiel and a galloping beat. This one is a sharp antidote to the winsome euphoria of “Whenever.” Lyrically, Marshall flips the script, sketching a lovelorn scenario of a forsaken, would-be Romeo. Anonymous in the madding crowd, he tries to pinpoint where it all went wrong; “I hear something in the sounds that surround me, that only seem to remind me that I’m lost and longing for a different place and time.” By the time the song arrives at the bridge, he seems ready for a change of seismic proportions; “It’s the place where we keep all our hopes and dreams, the place where I lost my heart it seems, all people looking for danger and romance, drop by there while you still have the chance, cause it’s all going to tumble down, it’s gonna shake apart and tumble to the ground.”

As with Marshall’s debut, the thematic throughline here seems to toggle between what Jimi Hendrix once characterized as Love or confusion. The exhilaration exhibited on “Monday Morning Rock,” a pithy and agile Rocker powered by a bongo-riffic beat, fluid bass lines and rippling guitars, is matched by playful lyrics that delay workaday responsibilities for a bit of carnal knowledge.

Conversely, “Try” swaps out peacocking for propinquity. Shang-a-lang guitars, darting keys and loping bass lines are wed to a vaguely Rockabilly beat on this romantic rapprochement. Feathery harmonies cocoon hopes of reconciliation; “Though nothing is clear, and I’m wondering how to save what’s left of us now, why don’t we try, try you and I?”

“One More Reason” sorta splits the difference. Jangly guitars partner with tensile bass lines and a locomotive rhythm. The propulsive arrangement belies sad-sack lyrics shot-through with suspicious sturm und drang; “So I take a walk outside, down streets that suggest to me, nothing more or less than a world full of misery, where did she stay last night, I’ve really got to know somehow, and another thing, could that be where she is right now?” A breakneck guitar solo caroms through the arrangement, closely shadowed by urgent “ooh-oohs,” but the heartache remains.

This record is genius front to back, but three songs stand out. “For Her Love” is an infectious declaration of love. Guitars ricochet between a boinging bass line and a boisterous backbeat, his exhilaration; “Laughing out loud to no one, thinking ‘bout the things I’ve done, for her love,” mirrors the buoyant melody and arrangement. Stuttery guitars preen and strut on the break just ahead of a gimlet-eyed happily ever after; “We walk together on a summer night, I close my eyes and I feel alright, and we’ll keep having our fun, heart to heart, even if the whole world falls apart.”

Meanwhile, “One Day With You” simply swaggers. Reverb-drenched guitar, slap-back bass, tinkly toy piano and a galumphing beat coalesce around a taut Rockabilly arrangement. Marshall’s stacked vocals leap tall buildings with a single bound, as he pledges undying fealty to an indifferent ex; “For one day with you, I would risk ruin, pain and degradation, for one day with you, I would gladly ruin my reputation, just to feel your hand resting on my knee, I’ll face danger, death and injury, oh believe me.” Jittery guitars crackle with romantic frisson on the break, while an extended instrumental outro spotlight’s Marshall’s fleet fretwork.

Finally, things take a twangy turn on the Countrified lament, “All I Know Right Now.” Twitchy guitars, shuddery bass, a heartbreak beat and a tambourine shake almost alleviate the angst that accompanies a final break-up; “I’m going to find a place where the music is loud and try and lose myself somewhere in the crowd, I might find someone who’s warm and kind, who can stop me from thinking about the trouble in my mind.” Guitars vroom ring and chime on the break, but the ache remains palpable. The original record closed out with “What Time Is It” and “Hold It.” Even then, MC had an encyclopedic knowledge of Pop, Rock, Country, Soul, Rockabilly and R&B so it’s no surprise he had a cool cover at the ready. The former, written by Bob Feldman, Jerry Goldstein and Richard Gottehrer, was originally a hit in 1962 for the Jive Five. He swaddles his version in lush instrumentation and swoony harmonies.

The latter clicks a snapshot, a specific moment in time when dreams of Pop stardom are coming true, and though it’s not perfect, he’s savoring it. Beatific harmonies wash over cascading guitars, see-saw bass and an elastic beat. The opening couplet paints a vivid portrait of early ‘80s malaise; “Rain on my window, Micharl (Jackson) on my radio, 737, this room I’m in, this moment won’t ever be here again.” Anthemic and slightly ambivalent, he offers a slice of conversational wisdom; “And whenever somebody tells you that all the good times are through, look into their eyes and tell them I’m surely glad that I’m not you.” Sly guitar licks dart through the break, as the track winds down the lyrics note “World’s in a hurry, too many worries, but I don’t want to lose everything I’ve gained, so I tell myself again and again…hold it…hold it.” And he repeats that final phrase, over a walloping drum salvo and stinging guitars. Like a wish, like a mantra, like a prayer.

Of course, being a reissue, a few bonus tracks pop up at the end, including “TV Track” versions of “Our Town” and “Monday Morning Rock.” Apparently, the instrumentation and backing vocals accompanied their live vocals for television appearances. There’s a “guide vocal” rendition of “What Time Is It.” But the true treasures here are a propulsive take on Hank Mizell’s slightly obscure, Rockabilly classic, “Jungle Rock,” a muscular version of Elvis Presley’s “Little Sister,” and a tart original instrumental, “AKA Durham Town.”

There’s a time-tested truism in the music biz: an artist has their whole life to make their first record. Then maybe 18 months to follow up with a second effort. Marshall Crenshaw deftly sidestepped what’s commonly referred to as “The Sophomore Slump.” The music here is as crisp and thrilling as his debut. But passionate fans and a more than a few critics griped about the dense production provided by Steve Lillywhite. The British producer had begun to make a name for himself helming seminal albums by The Psychedelic Furs, Peter Gabriel, XTC and U2’s first three albums, Boy, October and War. The latter garnered superstar status for the band and him when it was released a few months ahead of Field Day. 40 years on, the complaints seem petty and picayune. Right now, right here, in this moment, this record feels both classic and timeless.