By Eleni P. Austin

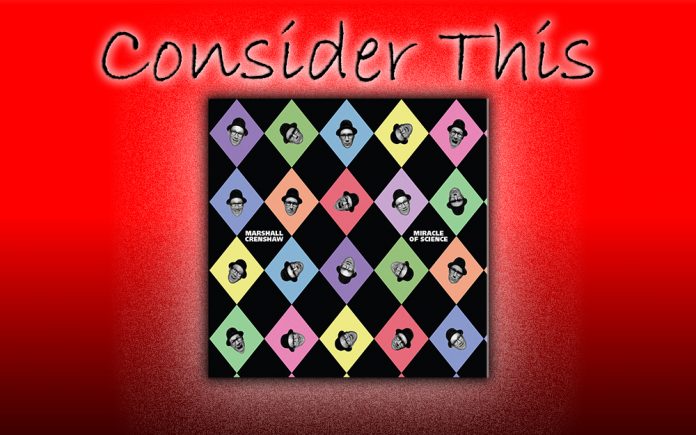

Have you ever bought an album just because it has a cool cover? A good cover can sometimes wield seductive powers, if it’s eye-catching or provocative. The imagery pulls you in, and hopefully, the music it contains is equally compelling.

The minute I saw Marshall Crenshaw’s debut, I knew that I needed to own it. It was 1982, Punk was sort of receding, New Wave was gaining a foothold in the Top 40, and it felt like anything was possible. Especially to this nearly 19 year-old Bitch Goddess, already obsessed with Elvis Costello, the Clash, the Jam, the Pretenders and happily discovering new stuff from Romeo Void, Haircut 100, X and The Blasters.

The cover was awash in dayglo colors. Sitting at a table accented by the kind of glazed Fiestaware that wouldn’t be out of place in the “Leave It To Beaver” household, sat Marshall Crenshaw. His bespectacled appearance was equal parts Lennon-esque and Buddy Holly-riffic. The decisive expression on his face promised those classic touchstones and so much more. I bought the record and it rarely left my turntable. I got the cassette for my car and played it so much it started to make that squeaky mouse sound, as the tape wore out. I loved that record so hard (I still do). Little did I know Marshall Crenshaw had been preparing his whole life to make that album.

Born in Detroit, Michigan in 1953, Marshall grew up in the nearby suburb of Berkley. He picked up the guitar at age 10 and by the time he was through with high school he had already played in a series of bands. By the time 1973 rolled around, Marshall had decided that current Pop music was pretty bland, narrow and exceedingly white. His obsessions hewed closer to the primitive Rock & Roll/Rockabilly of the ‘50s along with the swoony Soul style that was featured on his local R&B radio stations. These classic styles informed his own approach to songwriting.

Musically, Detroit felt like a wasteland, Motown had relocated to the West Coast, and by the end of the ‘70s, Marshall felt as though he’d reached a dead end. Opportunity knocked in the form of the Broadway show, Beatlemania, he auditioned and won the role of John Lennon. He survived a few intensive weeks of Beatles “boot camp” before the show premiered. Following runs in San Francisco and Hollywood, he spent six months on the road. While the experience was invaluable, it also convinced him that his true path lay in creating his own music. He bought a four-track recorder and never looked back.

Once he finished his Beatlemania commitment, he settled in New York City. Armed with an arsenal of demos, he recruited his brother Robert to play drums and auditioned about 30 bassists before connecting with Chris Donato. Relentlessly old-school, Marshall managed to walk the city, dropping off demo tapes to assorted record biz movers and shakers. Alan Betrock was the first to champion his sound. The multi-hyphenate (music writer/publisher/indie label president) released his first single “Something’s Gonna Happen” on his Shake Records imprint. Rockabilly revivalist Robert Gordon included a version Marshall’s “Someday, Someway” on his 1981 album, Are You Gonna Be The One. Pretty soon major labels were calling.

Marshall signed a deal with Warner Brothers Records and after an abortive attempt to produce his debut himself, the label suggested he enlist Richard Gottehrer, whom he had already met at a Robert Gordon session. Gottehrer helped shape the album’s sound, without sacrificing Marshall’s vision.

The result was an instant classic, released in the Spring of 1982, it felt like a breath of fresh air. Crisp and succinct, it reflected Marshall’s retro musical obsessions without ever feeling archaic or old fashioned. Hints of Rockabilly and Power Pop coexisted with Country Western and R&B. Critical acclaim was unanimous. His version of “Someday, Someway” reached the Top 40 and the album peaked at #50 on Billboard’s Hot 100 chart.

For the remainder of the ‘80s, Marshall released a string of excellent albums including Field Day, Downtown, Mary Jean & Nine Others and Good Evening. Although none reached the commercial heights of his debut, he cultivated a loyal and enthusiastic fan base. In the next decade he recorded three more studio albums, Life’s Too Short, Miracle Of Science and #447, as well as a live recording, My Truck Is My Home. He had also begun an acting career, appearing in Francis Ford Coppola’s “Peggy Sue Got Married,” as well as “La Bamba.” In the latter, he rather fittingly played his ‘50s doppelganger, Buddy Holly. Along with Syd Straw, he made occasional appearances on the Nickelodeon series, “The Adventures Of Pete & Pete.”

Something of a multi-hyphenate himself, Marshall has produced a Capitol Records compilation, Hillbilly Music…Thank God, and written Hollywood Rock: A Guide To Rock. Meanwhile artists like Bette Midler, Marti Jones, Kelly Willis and Ronnie Spector began covering his songs. He also co-wrote the Gin Blossoms massive hit, “Til I Hear It From You.”

Although he has only released three albums since 2003, What’s In The Bag, Jaggedland and #392: The E.P. Collection, he has remained busy, writing the title track for “Walk Hard,” a riotously funny Rock biopic parody film starring John C. Riley. He also began hosting his own radio program, “The Bottomless Pit” on WFUV. He recently regained ownership of the albums he released on the Razor & Tie label between 1994 and 2003. Among them is Miracle Of Science from 1996. That album has just been released on CD and vinyl for the time via Marshall’s own Shiny-Tone imprint.

The album opens with a random soundbite from the grade Z motion picture masterpiece, “Bela Lugosi Meets A Brooklyn Gorilla,” but that bit of bluster is quickly supplanted by “What Do You Dream Of?.” An elastic little Rocker, the winsome melody is powered by rippling guitars sinewy bass and a springy backbeat. The candy-coated crunch of the instrumentation serves as camouflage for slightly melancholy lyrics that reveal no matter how well we think we know our significant other, there’s always a secret part of them that remains hidden; “What do you dream of, I’ll never know what really lies behind your sleeping eyes…I’ll never solve your mystery, what do you dream of, while you’re lying next to me?”

Ever since his debut, Marshall has displayed a wide-ranging grasp of Pop music, astute cover songs have dotted each one of his albums, and that tradition continues here. “Who Stole That Train” was a modest hit for Country singer Ray Price. Marshall leans on the railroad motif, blending rumbly guitars, chugging bass clickity-clack rhythm, even a faint train whistle echoes in the distance as he awaits the return of a paramour. Lap steel and slide guitars careen through mix as guitars flicker, skitter and scorch throughout the song.

He takes a rustic approach on “The ‘In’ Crowd,” a huge hit for both R&B crooner Dobie Gray and Jazz pianist Ramsey Lewis back in 1965. Wily Dobro notes connect with a swinging horn section, muted keys and a snappy handclap beat. The lyrics remain a study in humility; “I’m in with the ‘in’ crowd…dressin’ fine, makin’ time, we breeze up and down the streets, we get respect from the people we meet/They make way, day or night, they know the ‘in’ crowd is out of sight.” Marshall doesn’t even have to blow his own horn, the blowsy brass accents have him covered.

“Twenty-Five-Forty-One” originally appeared 30 years ago on Intolerance, the first solo album from ex-Husker Du drummer, Grant Hart. While the original is yelp-y, jittery and primitive, Marshall’s take is streamlined and elegant; a wistful slice of nostalgia powered by caffeinated, heartbreak beat, twinkly mandolin and muscular guitars. Pithy lyrics limn the excitement of a new relationship that results in cohabitation; “We put down the money, we picked up the keys, we had to keep the stove on all night so the mice wouldn’t freeze/I put our name on the mailbox, and I put everything in the past…” Suddenly, it all unravels; “It was the first place we had to ourselves, I didn’t know it would be the last.”

“A Wonderous Place” was a quavery hit for British singing sensation Billy Fury in 1960. Simple and swoony, the gooey opening couplet says it all; “I found a place full of charms, a magic world in my baby’s arms, her soft embrace like satin and lace, a wonderous place.” In Marshall’s hands it’s transformed. The arrangement is lush and languid, propelled by rapid bongo fills, see-sawing violins and cellos, spidery bass lines, shimmery guitars and sultry vibraphone. The reverb-drenched guitar solo splits the difference between surfin’ and spyin’.

The best tracks on the record mine Marshall’s incandescent, seemingly effortless sense of songcraft. The lithe melody of “Laughter” is anchored by a bumptious backbeat, boomerang bass lines and stacked acoustic, electric and E-bow guitars. Although the arrangement sparks and pinwheels, the opening lines sketch out a scene of yearning and heartbreak; “It’s almost dawn and everything’s wrong, I’m wide awake and angry all night long, chained to my rocking chair/Sometimes it’s hard to bear, so hard to bear, the memory of the laughter that we used to share.” A searing guitar solo on the break underscores the ache.

On “Starless Summer Sky” spangled guitars lattice over prowling bass lines and a tumbling beat. His still-boyish tenor hits an astral plane as he unspools an uncomplicated love story; “We sit and gaze into each other’s eyes, and we kiss beneath the starless summer skies, sometimes the best words are left unspoken, sometimes the best words are left unsaid.” The song is an instant classic, sweet without being cloying or saccharine.

“There And Back Again” is stripped-down, yet cinematic. Chiming acoustic guitars ride roughshod over loose-limbed bass fills and a rattle-trap rhythm. A nuanced narrative sets the tone for a rueful recollection of lost love. From the exhilarating beginning; “She was wild and I was restless and our love was true, we were young and time was endless, everything was new, driving fast and running breathless, (it) blew my heart away,” to it’s inevitable dissolution; “It lasted ‘till it ended, that’s how it goes, sometimes things are just over, everybody knows/Time has made us into strangers, she’s lost to me now.” A baritone guitar revs and retreats accentuating the emotional highs and lows, adding courtly Spanish filigrees and Country flavored licks.

Other interesting tracks include the urgent fragility of “Only An Hour Ago” and the lissome and nimble instrumental, “Theme From ‘Flaregun’,” which showcases MC’s fleet fretwork. The album properly closes with the suitably Psychedelicized “Rouh Na Selim Neves.”

The reissue also includes three bonus tracks. A couple more cover tracks display his encyclopedic musical knowledge as he Crenshaw-izes (Marshall-izes?) “What The Hell I Got,” and “Misty Dreamer.” The former was a huge hit in 1974, for Canadian musician Michael Pagliaro, that garnered radio airplay in Michigan. The latter is a song from Scottish indie pop artist, Scott Wylie. Also on deck is the jack-rabbity Jangle Rock of “Seven Miles An Hour,” the forward version of the backwards “Rouh Na Selim Neves.”

Back when he first burst on the scene, Marshall Crenshaw’s music felt Classic, managing the neat trick of feeling fresh, yet familiar. He managed to coalesce myriad influences without ever sounding mannered or derivative. I’m as in love with him now as I’ve ever been, his music is timeless. And his album covers are still pretty cool too.