By Eleni P. Austin

“Our pathways are magnetic, our logic is synthetic/Our struggle is so pathetic, and a bore”

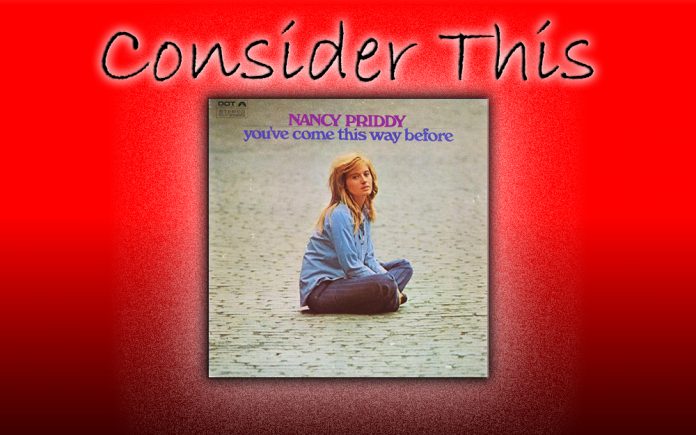

That’s Nancy Priddy weighing in on the state of the world. It seems au courant, but she wrote those lyrics more than half a century ago.

For a brief period in the mid-to-late ‘60s, Sunshine Pop, Country, Lounge, Folk-Rock and Psychedelia kind of collided. Bands with names like Free Design, Peppermint Rainbow, the Lemon Pipers, Sunshine Company and The Yellow Balloon, along with chanteuses like Claudine Longet, Dusty Springfield and Nancy Sinatra synthesized these sounds, But no one exemplified the convergence of genres better than Nancy Priddy.

Nancy grew up in South Bend, Indiana, initially, she studied Liberal Arts at Oberlin College before transferring to Northwestern. She was majoring in drama, but soon she began cutting classes to play with some local Jazz musicians. After college she relocated to New York, trying to break into show business, typically, she starved for her art. Finally, she joined the touring company for “Absence Of A Cello,” featuring esteemed character actor Hans Conried, (best known as “Uncle Tonoose” on Danny Thomas’ “Make Room For Daddy” television series). But during the show’s Chicago run, she managed to corral her musically-inclined pals and record a series of demos.

There was a lengthy stint in Los Angeles where she landed a lot of acting jobs, in her spare time she could be found in all manner of makeshift recording studios, adding vocals to friends’ instrumental tracks. Pretty soon she returned to Chicago and then New York. For a time, she was part of a Greenwich Village Folk collective known as the Bitter End Singers. It was around then that she connected with producer Phil Ramone.

Phil encouraged her to write her own music and rather quickly, he was producing her debut, “you’ve come this way before.” Collaborating with arranger Manny Albam, the album was released in 1968 to minimal fanfare via the Dot record label. Soon Nancy was back in L.A., where she cut the single “Feelings” with Harry Nilsson. Her vocals were also featured (but uncredited), on the epochal debut, “Songs Of Leonard Cohen.” By this time she had also met Dot Records staff producer Robert Applegate. The couple married , Nancy set aside her musical aspirations and concentrated completely on her acting career.

Throughout the ‘70s she made appearances on wildly popular television shows, from “Bewitched, “Barnanby Jones” and “Medical Center” to “Cannon,” “Police Woman,” “Quincy” and “The Waltons.” In 1971, she and Robert welcomed a daughter, Christina. But by the end of the “Me Decade” the couple divorced.

Throughout the ‘80s, Nancy and Christina both found acting work on the small screen. In 1987, Christina was cast in the raucous and raunchy TV series, “Married With Children” She found fame as the ditzy, sex-crazed daughter, “Kelly Bundy.” Juggling her commitment to that show, which lasted a until 1997, Christina starred in films like “Don’t Tell Mom The Babysitter’s Dead,” “Mars Attacks!” and “The Big Hit.” As Christina toggled between television and film commitments, the time seemed right for Nancy to revive her singing career. Since the turn of the 21st century, she has released three well-received album’s “Christina’s Carousel,” Mama’s Jam” and “Can We Talk About Now.” Somewhere along the line, aficionados of ‘60s Psychedelia discovered “you’ve come this way before.” The British reissue label, Rev-Ola released the album on CD in 2005, but the original LP has been long out of print. Luckily, the folks Sundazed Music and Modern Harmonic Records have partnered to reissue the album on vinyl for the first time.

The record opens with the title track. Stuttery guitar riffs lattice over shivery keys, wily bass lines and a syncopated beat. Nancy’s vocals are equal parts elegant and earthy. The opening couplet is suitably lysergic; “Feeling strange sensations, familiar old vibrations, somehow I know your radiation to the core.” As the instrumentation kicks in, the song evinces a sense of Deja’ Vu. Guitars and keys get swirly on the break and her come-hither mien draws the listener in.

Both “Christina’s World” and “O Little Child” evoke a feeling of guileless and innocence. The former, was inspired by the famous Andrew Wyeth painting. Plucked guitar arpegios are buttressed by a lowing string section and chunky percussion. The lyrics’ vivid imagery feels far more lush and opulent than Mr. Wyeth’s stark and desolate figure; “Christina’s world was a world of a willow trees…a world of ‘Allay, allay all in frees,’ fingers crossed and ‘whispers please,’ talking to someone no one sees, lightnin’ bugs at sundown, Christina’s World.” Unsurprisingly, Nancy named her daughter after both the painting and the song.

The latter is a loping Waltz. Jangly guitars connect with chiming harpsichord fills, fluttery organ and with brass accents that recall Herb Alpert’s South of the Border flavor. Nancy easily slips into the skin of an adult in the September of her years who covets the carefree life of a kid. Setting aside her envy, she allows herself to be beguiled by the child’s innocence; “So Alive you’ve made me feel, in a world all made of Spring…” The song is Jazzy and slinky in all the right ways.

The best songs here are at once effortless, cosmopolitan and somewhat outre.’ “And Who Will You Be Then” displays a sharp sense of Soulful sophistication. The arrangement and instrumentation, from the stabby keys, roiling bass lines, serpentine guitars and pulsating rhythms, echo the hyperkinetic songcraft of Quincy Jones. The piano-driven melody is nearly supplanted by Nancy’s sanguine delivery, even as trenchant lyrics allude to an abusive relationship and an endless cycle of violence and reconciliation; “And who will you be then, when somewhere it all begins again/You’ll pray this time won’t be the same, but who will you be then?”

“My Friend Frank” completely switches gears, leaning closer to the primitive cool of Rockabilly. Twangy guitars are matched by nimble bass lines, a wash of dissonant organ and a rattle-trap beat. The melody’s loose-limbed joy belies lyrics that paint Frank as a bit of an Eeyore; “My friend Frank, why have you just shrugged? Has something special just come unplugged? You look a little bugged, my friend Frank.” The tempo accelerates on the break, veering from monochromatic black and white to vivid technicolor.

“We Could Have It All” borrows liberally from the Burt Bacharach playbook. Flatulent flugelhorns are bookended by sinewy guitars, stately harpsichord, angular bass and some tensile hi-hat action. Here Nancy plays the part of a sunny seductress promising; “We could have it all, relax and let me show you, the games are far below you.”

“Mystic Lady” is the album’s centerpiece. Opening with insistent “busy signal” piano chords, it shares some musical DNA with Harry Nilsson’s “One.” She adds a soupcon of broken circus music, powered by mincing keys and pastoral woodwinds. The arrangement shapeshifts several times, giddy and effervescent one minute, pensive and dour the next. Honeyed harmonies stack atop shang-a-lang guitars agile bass lines and a tick-tock rhythm, rendering nursery rhyme instructions like “Ride a cockhorse to Banbury Cross to see what they’ve lost” somewhat moot. By the homestretch, the song locks into a gospel groove. Churchy piano chords shadow Nancy’s surprisingly Aretha-esque exhortations to “stay on lady” to the bitter end. It’s quite simply a tour de force.

Other interesting tracks include the modal shimmer of “Ebony Glass” and the strobe-light Frug of “On The Other Side Of The River.” The album closes with “Epitaph.” Rippling piano notes anchor this stunning tone poem. Musically, Jazz and Classical styles intersect. Nancy’s vocals hug the melody’s hairpin turns, mirroring the mythical dualism Robert Blake once referenced with “Songs Of Innocence And Experience.”

Heady, provocative, dreamy, these are just a few ways to describe the aural banquet contained in the grooves of “you’ve come this way before.” Nancy Priddy’s debut was ahead of the curve half a century ago. In some ways, it still is today.