By Eleni P. Austin

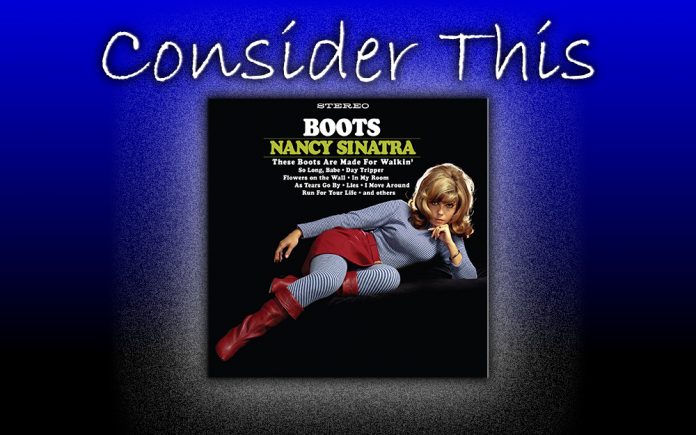

If you think Nancy Sinatra’s musical career begins and ends with her #1 smash hit, “These Boots Are Made For Walkin’,” then you haven’t been paying attention. Although she was born into musical royalty, she mostly made her own way throughout the Swingin ‘60s.

The eldest child of Frank Sinatra and Nancy Barbato, Nancy was born in New Jersey, but grew up in Los Angeles with her younger siblings, Frank, Jr. and Tina. Her singing career began in her late teens. Initially, she was paired with prolific producer, Tutti Camarata, who’d had some success with Disney star Annette Funicello. They recorded a few songs that were well-received overseas but seemed a bit too treacly and teenage for her.

Nancy struck a bargain with her dad, if he signed her to his label, Reprise Records, she would be responsible for paying her expenses and covering her recording sessions. She floundered for a bit, but then label President Jimmy Bowen suggested she collaborate with Lee Hazlewood. The Oklahoma-bred producer/singer-songwriter had been making hits in Hollywood for about a decade, most notably with Duane Eddy.

Lee auditioned a few songs for Nancy and she was in. He quickly enlisted guitarist Billy Strange to work on new arrangements. Her first single, “So Long, Babe,” b/w “If He Loved Me,” began inching up the charts and soon she was booked on TV shows like Hullabaloo and Shindig. Her follow-up single, “These Boots Were Made For Walkin’,” released just ahead of her first official long-player, Boots, was a game-changer. Both the single and the album shot to the top of the charts. That was just the beginning. Nancy released a string of albums throughout the ‘60s that included indelible songs like “How Does That Grab You, Darlin,” “Sugar Town,” and the theme song from the James Bond film, “You Only Live Twice.” She teamed with her dad for her second #1 hit, the ballad, “Somethin’ Stupid.” She also partnered with Lee Hazlewood for a series of arch duets; “Summer Wine,” “Jackson,” “Some Velvet Morning” and “Sand.” Around the same time, she launched her acting career, appearing alongside Peter Fonda in The Wild Angels and Elvis Presley in Speedway.

When she married in the ‘70s, she deliberately cut back on making music, preferring to concentrate on family. Throughout the decades, her influence was felt. Her songs were featured in films like Full Metal Jacket and Kill Bill. In 2004 she released a self-titled album which found her collaborating with a younger generation of admirers like Morrissey, Jarvis Cocker of Britpop sensations, Pulp, Pete Yorn, Steven Van Zandt and Bono and The Edge from U2.

Recently, Light In The Attic Records released a career-defining retrospective, Nancy Sinatra: Start Walkin’ 1965-1976.” Simultaneously, they offered up an expanded edition of her trailblazing debut, Boots. Up until the Beatles’ groundbreaking Sgt. Pepper album, records typically included one, maybe two hit singles, and the rest of the long-player consisted of filler. Although Boots arrived a year earlier, it’s clear that Lee and Billy took care with the song selection. Lee picked each song, but Nancy retained veto power.

Boots opens with “As Tears Go by,” a nascent composition from Mick Jagger and Keith Richards that was a hit for Marianne Faithfull in 1964. The original was a lachrymose ballad (the Stones recorded their own version a year later, only marginally dirtying up the pretty). In Nancy’s hands, it opens with her breathy croon atop courtly Spanish guitar and lowing bass notes. But it quickly shapeshifts, layering in thwoking percussion, sparkly keys and sun-dappled guitars, locking into a breezy Bossa Nova arrangement. Her sanguine contralto radiates such self-assurance that lyrics like “My riches can’t buy everything, I want to hear the children sing, all I hear is the sound of falling rain on the ground, I sit and watch the tears go by” feel less maudlin and more contemplative.

Nancy stakes her claim in the firmament of the burgeoning Pop/Rock scene by assertively covering songs by acknowledged master craftsmen, The Beatles and Bob Dylan. Not once, but twice does she redefine hits from the Fab Four’s catalogue o’ hits. First up is a playful take “Daytripper.” While the original employed a fusillade of guitars to open the song, Nancy and company get their point a across with harumph-ing trombones, some sly guiro action, and a pummeling backbeat. Rather quickly, a brassy fanfare, descending bass lines, shang-a-lang guitars and plinky piano are folded into the mix. Nancy’s mien is derisive as lyrics dismiss a commitment-phobic hipster; “Got a good reason for taking the easy way out, got a good reason for taking the easy way out/He was a daytripper, one way ticket yeah, it took me so long, but I found out, I found out.” The horn section shadows Nancy on the verses, acting as a wordless Greek chorus. On the break, salty horns are matched by a peppery big beat.

Toward the end of the album, she tackles “Run For Your Life.” Countrified acoustic guitars partner with stinging electric riffs, tensile bass, frowzy horns, Honky-Tonk piano and a boomerang beat. Although the original lyrics were equal parts misogynist and slightly homicidal, Nancy cannily flips the script, warning a faithless swain that she won’t tolerate any misbehavior; “Well, you know that I’m a wicked chick and I was born with a jealous mind, and I can’t spend my whole life trying just to make you toe the line/You better run for your life if you can, little boy, hide your head in the sand, little boy, catch you with another girl, that’s the end, little boy.” The tempo accelerates on the break, downshifting into a Watusi-fied feel.

Nancy joined a long line of Dylan admirers like Johnny Cash, Joan Baez and The Turtles when she put her imprimatur on “It Ain’t Me Babe.” Once again, she zigs where the others might have zagged, choosing to couch the melody in a fluttery Samba arrangement. Syncopated horns fall in line with tinkly percussion, Paisley keys and a walloping beat. Dylan’s cranky kiss-off amps up the vitriol. But Nancy’s smooth croon takes the sting out of blunt couplets like “Go way from my window, leave at your own chosen speed, I’m not the one you want babe, I’m not the one you need/You say you’re lookin’ for someone who’s never weak but always strong, to protect you and defend you, whether you are right or wrong, someone to open each and every door, but it ain’t me babe, no, no, no, it ain’t me babe, it ain’t me your looking for.”

The best tracks showcase Nancy’s ability to hopscotch genres. “So Long, Babe,” her first collaboration with Lee Hazlewood, blends scratchy guitars, shivery strings, sprightly keys, upright bass, tumbling drums and a hint of trumpet to create a Country-Pop symphony. Addressing a wayward beau, her manner is equal parts empathetic and aloof; “I know you’re leaving babe, goodbye and so long, you never made it babe, I wonder what went wrong, they never understood your songs, here’s what you do, just walk away and leave ‘em, and let ‘em follow you.”

The flipside of the “So Long, Babe” single, “If He’d Love Me,” deftly switches gears. A lush Torch song, it weaves a tapestry of swirly strings, delicate percussion, thunking bass, sugar-rush guitars and a relaxed tick-tock rhythm. Much like Mr. Mojo-Risin,’ Nancy wallows in the mire, soaking in the heartache and caressing lyrics like “Here I am, all alone and crying, bluer than I’ve ever been, in my heart it feels like I’m dying, thinking what might have been, if he loved me like I loved him.”

The Statler Brothers’ hokey “Flowers On The Wall” is completely recalibrated. Spiraling guitars collide with brass accents, wily bass and a tom-tom beat, creating a Bluegrass-Mariachi hoedown. Nancy’s voice drips with sarcasm as she reassures a former flame that, despite his absence, her life is action-packed; “While you and your friends are worryin’ ‘bout me, I’m havin’ lots of fun, countin’ flowers on the wall, that don’t bother me at all, playin’ solitaire ‘til dawn, with a deck of fifty-one, smokin’ cigarettes and watchin’ ‘Captain Kangaroo,’ now don’t tell me I’ve nothin’ to do.”

Of course, the record’s piece de resistance remains the title track. Some 55 years later, it’s lost none of it’s allure. Rather famously, Lee Hazlewood wrote the song and was hoarding it for himself, but Nancy accurately argued that a man singing that song “was chauvinistic and ugly, but a little girl singing it gave it a whole different thing.” Clearly, she made her point. The song opens with that iconic quarter-tone bass line, jangly guitars fall in, tethered to a clip-clop rhythm and a tambourine kick. Much like Aretha Franklin did with Otis Redding’s “Respect,” from the minute she opens her mouth, Nancy takes ownership of this song. With an authoritative growl in her voice, she never backs down. Syncopated horns punctuate each neatly-turned phrase as her suspicions mount; “You keep lyin’ when you oughta be truthin’ and you keep losin’ when you oughta not bet, You keep samein’ when you oughta be a-changin,’ now what’s right is right, but you ain’t been right yet/These boots are made for walkin’ and that’s just what they’ll do, one of these days these boots are gonna walk all over you.” As the song nears completion, she’s tossed this sad Casanova to the curb; “Are you ready boots, start walkin.” The horn section revs, locking into a Go-Go groove and Nancy Frugs off into the sunset.

Other interesting tracks include a springy take on the Knickerbockers’ taut Garage Rocker, “Lies,” then there’s the glossy “I Move Around.” Finally, “In My Room” evinces a Spectorian Wall Of Sound majesty without the Wagnerian heft.

Boots originally ended on “Run For Your Life,” but the reissue includes two bonus tracks to close the set, “The City Never Sleeps At Night” and “For Some.” Lee Hazlewood originally wanted the former to be the “A” side of the “Boots..” single, Nancy disabused him of that notion and history is on her side. It’s just a bit of Bubblegum fluff. The latter, she recently dismissed as a “terrible, terrible song.” It does just kind of sit there. A little too Doo-Wop-y for the Swingin’ ‘60s.

Nancy Sinatra took control of her career early on and was sharp enough to trust Lee Hazlewood’s vision. What Lee characterized as a dumb sound,” which didn’t mean stupid, so much as uncomplicated. Shaping that sound were a loose collective of musicians informally known as The Wrecking Crew. They included bassists Chuck Berghofer, Donald Bagley and the incomparable Carol Kaye, drummers Hal Blaine and Donald “Richie” Frost, guitarists Al Casey, Nick Bonny, Jerry Cole, Ervan Coleman Donnie “Dirt” Lanier, Lou Morrell, Donnie Owens, Bill Pitman and Billy Strange, Don Randi and Larry Knechtel on keys. Emil Richards, Gary Coleman and Frank Capp on percussion. A string section that included Emmet Sargeant Joseph Ditullio, Jesse Erlich and Joseph Saxon on cello and William Miller on violin. A horn section comprised of Roy Caton and Oliver Mitchell on trumpet, Plas Johnson on Saxophone, Lew McCreary on trombone, plus Richard Perissi on French Horn.

All of these elements coalesced on Boots, which made a lasting impact, paving the way for everyone from Blondie’s Debbie Harry to Madonna to Lana Del Rey. Nancy Sinatra remains a trailblazer, a legend and a badass. Don’t let anyone tell you anything different.