By Heidi Simmons

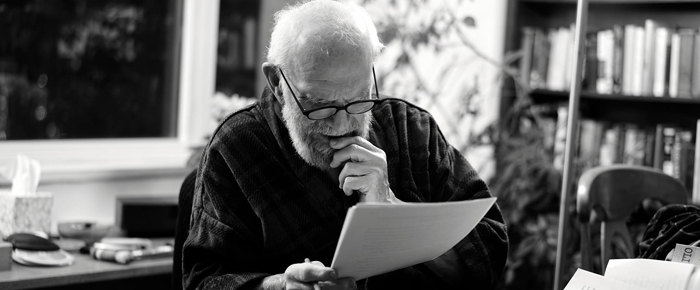

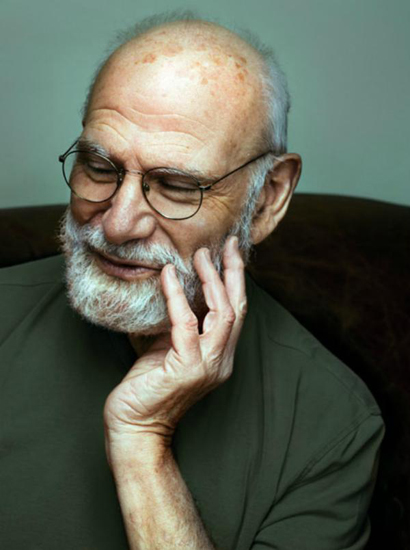

It is a rare gift when a writer has the ability and talent to open the eyes and mind of a reader to new ideas, colorful worlds and human idiosyncrasies. It is even more exotic and fascinating when the author is a neuro-scientist and medical doctor. Oliver Sacks not only had a passion for people, but for language and narrative.

It is a rare gift when a writer has the ability and talent to open the eyes and mind of a reader to new ideas, colorful worlds and human idiosyncrasies. It is even more exotic and fascinating when the author is a neuro-scientist and medical doctor. Oliver Sacks not only had a passion for people, but for language and narrative.

Last Sunday, August 30, Sacks died of cancer at the age of 82 in his New York home.

When Sacks was 14 years old, he began to journal. Born and raised in England, Sacks’ parents were both physicians; his mother a surgeon and father a general practitioner who worked from home. Sacks was the youngest of four boys. His two eldest brothers became medical doctors as well. The other, just as brilliant, became schizophrenic. Perhaps influencing Sacks’ interest in the mind.

In the 1960s, Sacks came to the United States to further study and practice medicine. In England, homosexuality was illegal, so when he came to California, he found friends and a lifestyle he could not have had back home. Sacks always wanted to become an American citizen, but never did.

Keenly observant, insatiably curious and a brilliant scientist, it became natural for Sacks to express his work and thoughts on paper. He loved the act of writing. As a doctor, his case histories and clinical insights stood out. Publishing research results was a breeze — and fun. The writing helped advanced his career.

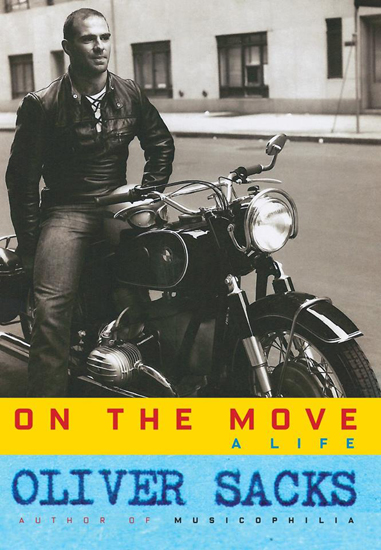

Often, for competing physicians, his highly readable pathographies were a threat. His first book on migraines was a result of working at a New York clinic. He wrote Migraine while on vacation in England visiting his folks. “It spilled out suddenly, without conscious planning,” he says in his biography On The Move (for my review go online CVW Book Review.)

When Sacks handed his manuscript to the physician in charge of the migraine clinic, he was furious and threatened to destroy Sacks’ career. One doctor said that Sacks’ “book was too easy to read and would make people suspicious.” Shortly after, the jealous physician plagiarized the entire book declaring he wrote it! He never believed Sacks would have the gall to publish it after his scolding.

The migraine admonishment hurt Sacks and for a while he feared for his career as a neurologist and writer — until Awakenings. Working in a Bronx encephalitis ward, Sacks discovered a treatment to bring the patients back to cognitive life. The book became a best seller and a movie staring Robin Williams.

Books that followed: A Leg to Stand On; The Man Who Mistook His Wife for a Hat; Seeing Voices: A Journey Into the World of the Deaf; An Anthropologist on Mars; The Island of the Colorblind; Uncle Tungsten: Memories of a Chemical Boyhood; Oaxaca Journal; Musicophilia: Tales of Music and the Brain; The Mind’s Eye; Hallucinations; and his memoir, released this year, On the Move: A Life. Oaxaca is mostly a travel adventure, although it contains scientific observations.

Books that followed: A Leg to Stand On; The Man Who Mistook His Wife for a Hat; Seeing Voices: A Journey Into the World of the Deaf; An Anthropologist on Mars; The Island of the Colorblind; Uncle Tungsten: Memories of a Chemical Boyhood; Oaxaca Journal; Musicophilia: Tales of Music and the Brain; The Mind’s Eye; Hallucinations; and his memoir, released this year, On the Move: A Life. Oaxaca is mostly a travel adventure, although it contains scientific observations.

My favorite books by Sacks are: The Island of the Colorblind and The Man Who Mistook His Wife for a Hat. In Colorblind, Sacks goes to the Pacific islands Pingelap and Guam where each culture has a genetic defect mainly derived from their isolation and small gene pool.

With incredible intelligence and compassion, Sacks describes the life of islanders who live without color on one island and a strange paralysis on the other. His descriptions are poetic and beautiful. The reader understands what it’s like to be colorblind or unable to move.

Sacks not only helps the islanders as a doctor, but also takes time to experience the flora, fauna and island wonders. He writes about the history, society and culture with insight, respect and admiration, that Sacks is like an early explorer romanticizing the noble savage and rare fruits. It’s wonderful!

The Man Who Mistook His wife for a Hat is a colorful collection of twenty plus essays about his patients who suffered from different kinds of brain dysfunctions. Some include: Visual agnosia, in which a man cannot differentiate his wife from a hat; Korsakoff’s syndrome, happens when a patient cannot form new memories; and a lady with proprioception lost the ability to know her legs from her arms.

These stories are more than just case histories. Sacks presents these brain conditions not as pathetic curiosities, but as interesting human beings functioning with a fascinating brain anomaly. With science he clarifies the neurological disconnect, with compassion he makes their lives matter as if their problem were an enlightening gift. The information he learns, gleans and presents humanizes those who suffer and shows us a side of ourselves.

Sacks not only explored the mind, he challenged and tested it. He saw his patients as people, not subjects, and he made every effort to connect and make a difference. As a result, many of his patients thrived despite their disorder.

In his autobiography, Sacks does not talk about death or being ill. Perhaps at the time of the publication he did not know that his once excised melanoma had spread. He describes himself as a writer first and doctor second.

Oliver Sacks celebrated the miracles and mysteries of human cognition by writing about it in a language we can all understand. He loved music, life and words. He will be missed, but his work will live on. Thank you OWS. Rest in peace.