By Eleni P. Austin

“The hourglass never really runs out of sand, you get to the end and you just turn it upside down again/It’s like a book where the story never ends, the plot keeps turning around.”

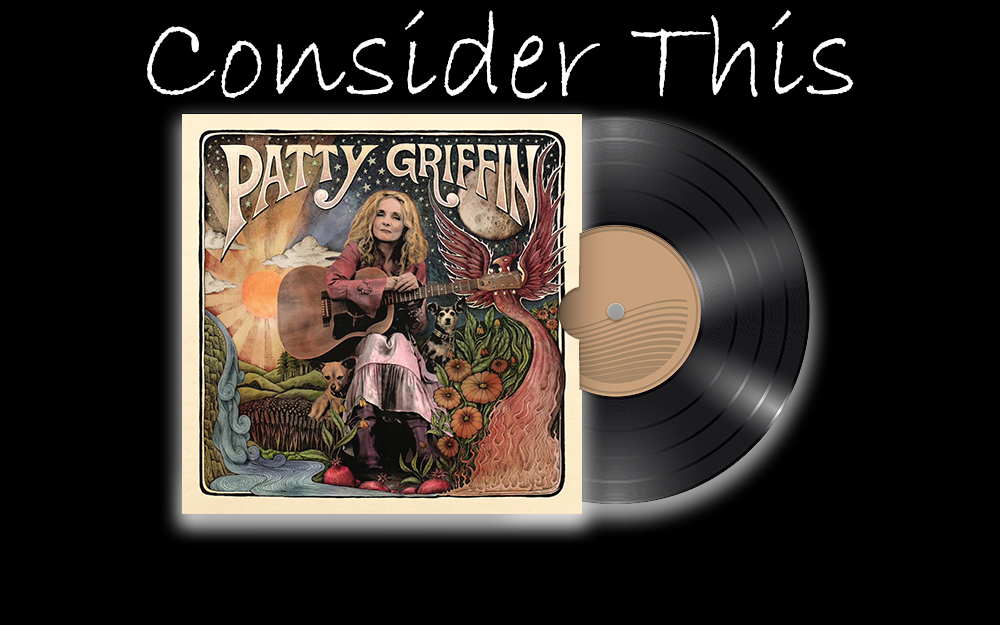

That’s Patty Griffin waxing philosophical on “Hourglass,” a song featured on her brand-new album, simply entitled Patty Griffin. It follows a two-year battle with breast Cancer.

Patty grew up in Maine, the youngest of seven children. As a kid, her dad bought her the Beatles’ Sgt. Pepper album for her birthday, it changed her life, inspiring her to buy a guitar for $50.00. By the age of 16, she was composing her own songs. A brief marriage following college took her to Florida, before she landed in Boston. As the marriage ended, she decided to pursue a career in music.

She made her bones playing local Boston Folk clubs. Rather quickly, her demo tape reached A&M Records and they offered her a deal. The label added touches of piano and guitar to her simple but eloquent songs and Living With Ghosts was released, as is, in 1996.

Her debut easily encompassed the genres of Folk, Country and Rock, but Red, her 1998 follow-up was more demanding, adding elements of Trip-Hop to the mix. Surprisingly, A&M passed on her third effort, entitled Silver Bell, so she split the label and quickly landed at ATO, Dave Matthews’ artist-friendly boutique label, distributed by BMG. Re-recording some Silver Bell cuts along with some new songs, the new album was entitled 1000 Kisses and arrived in 2002.

For that record, she upped her game considerably, creating indelible character studies like “Chief,” “Making Pies” and “Rain.” Other musicians took notice, and artists as disparate as Dixie Chicks, Bette Midler, Emmylou Harris Solomon Burke and Jessica Simpson began covering Patty’s songs.

She followed 1000 Kisses with an array of impeccably crafted records. Between 2003 and 2007 she released the live Kiss In Time, Impossible Dream and Children Running Through. Three years later she teamed with musician/producer Buddy Miller and recorded Downtown Church, an album of

Traditional Gospel Songs, plus three originals. After four previous nominations, she won her first Grammy.

Her association with Buddy led to her next high profile project, joining Robert Plant’s new band. In the years before Led Zeppelin, the would-be Golden God of Rock fronted a group called Band Of Joy. He resurrected the moniker for a new ensemble that included Buddy, singer-songwriter Darrell Scott, drummer Marco Giovino, bassist Byron House and Patty.

The ‘60s incarnation of BOJ was primarily a Blues-Rock outfit, the 21st century version became a wicked combo-platter of Blues, Folk, Country, Soul and Americana. Front and center was the combustible vocal chemistry between Robert and Patty. That frisson spilled over into their personal lives as well, and the couple began splitting their time between Patty’s house in Austin and Great Britain.

Her next solo outing, 2013’s American Kid was triggered by the terminal illness and death of her beloved dad, Lawrence Joseph Griffin. The record split the difference between a tender farewell and a celebration of life. In the tradition of the Byrds and the Book Of Ecclesiastes, it offered a time to mourn and a time to dance. Featuring two duets with Robert Plant it hit #36 on the Billboard charts.

Predictably, A&M (now a subsidiary of the monolithic Universal Music Group), tried to cash-in on her success, by releasing Silver Bell in 2014. They even had the, um nerve to market it as her “long-lost album.” It was a wonderful addition to her canon, and a boon for longtime fans. Around this time Patty and Robert amicably parted ways. While promoting his excellent Lullaby And…The Ceaseless Roar album he blamed the break-up on his “Black Country moods.”

A year later, Patty returned with her ninth studio effort Servant Of Love. The album explored the emotional fall-out from her break-up and also delved into some pointed social commentary. It netted her a seventh Grammy nomination.

Although her breast cancer was diagnosed early, the road to recovery was arduous, for a time she lost her voice and wondered if she would be able to make a living. But she persevered through exhausting treatment, and when she felt up to it, began recording music in her house with longtime collaborator Craig Ross. The result is a relatively intimate affair.

The record opens tentatively with the Countrified chanson “Mama’s Worried.” It’s just Patty and rippling Flamenco guitar notes. Her expressive voice equal parts Torch and Twang as she unspools a tale of a working single mother with the weight of the world on her shoulders. The lyrics conjure up images of James M. Cain’s “Mildred Pierce,” the (fictional) prideful, maternal warrior who managed make ends meet during the Great Depression; “She starts singing in the morning, she works and sings all day/Singing sad, singing low, for a while the worry goes away.” It’s a haunting tableau.

Patty continues that novelistic approach on three more tracks, offering rich narrative touches. On “Had A Good Reason,” she effortlessly inhabits a young daughter whose mother has abandoned her. The instrumentation is bare-bones, just Patty and her guitar, addressing a mother in absentia; “I guess you’re never gonna come back for me Ma, with a suitcase of pretty dresses and shoes/One for you and one for me Ma, and perfume for the ladies looking after me too.” There’s no guilt, no blame. In fact, she completely absolves the mother, rendering the song all the more heartbreaking.

On “Boys Of Tralee” the instrumentation fuses propulsive acoustic guitars and piquant percussion. The lyrics paint a vivid portrait of the immigrant saga. For centuries now people have suffered hardship and unimaginable sacrifice, making their way to America, the promised land, crossing oceans (or rivers), hoping for opportunity. In the 1800s, the Irish were as reviled (by certain segments of the population), as Mexicans and Central Americans today. This story centers on four boys from Ireland voyaging to North America for factory jobs, only three make it; “One morning our boy Tommy lay dying beside me, cold and sick and dying and blue was what we found/Before he took his last breaths the ship’s sailors found him, before he took his last breath they tossed him in to drown.”

“Bluebeard” is dour and menacing, marrying French Folklore to the American Murder Ballad tradition, propelled by a pair of acoustic guitars, two (!) marimbas, distant cello, and supple bass lines. Gothic and brooding, the lyrics center on a clear-eyed maiden who marries a man whose “eyes were black and his beard was blue.” Despite familial warnings she pledges her love and loyalty, but when she betrays his trust, discovering his deepest secret, he exacts vengeance; “The man came home to take her life, to cut her throat with a cold gray knife to lay her there with all the rest/Blood and bones and faded dress, to cast her in the deepest darkness.”

Rest assured, this record isn’t nonstop sturm und drang. More than a couple of tracks are buoyant and lively. The aforementioned “Hourglass” splits the difference between Gypsy Jazz and New Orleans Second Line. Strummy acoustic guitar is buttressed by a high-stepper rhythm, woozy trombone, fluttery organ and angular bass. As Patty channels her inner Bessie Smith a prickly, syncopated guitar solo echoes the late great Django Reinhardt. Despite sage advice that cautions “Don’t go swimming where the river’s too deep,” Patty quietly ignores the admonition; “I knew all along that it just wasn’t me, I went swimming in the river with the ghosts and debris/Shouldn’t a person at least try to be free, instead of giving up and just pretending to be?”

“The Wheel” is also a playful back porch ramble accented by gutbucket guitars and a swivel-hipped rhythm. However, the lyrics are deadly serious, referencing the continued Black Lives Matter struggle, and specifically, the murder of Eric Garner. Police attempted to arrest him in Staten Island, he resisted and a police officer got him in an (illegal) chokehold. Asthmatic and obese, he complained 11 times that he couldn’t breathe, before becoming unconscious. By this time, three uniformed and two plainclothes officers were surrounding one guy, whose crime was selling loose cigarettes. As they waited for an ambulance, none of the officers attempted to resuscitate Garner. He had a heart attack and died en route to the hospital.

Patty’s rage is palpable as she sketches out the horrific details; “Here’s a song about a man, about a man I never met, here’s a song about a man, about a man I can’t forget/Choked to death by a policeman, said he could not catch his breath, choked to death by a policeman, for selling single cigarettes.”

The album’s best tracks seem to look inward. “Where I Come From” is powered by slippery acoustic riffs, lonesome lap steel and a chugging backbeat. Patty offers a warts-and-all portrait of a hometown suffering economic hardship and cultural ennui, but there’s still some beauty to be had. On the break, sun-dappled baritone guitar connects with lilting lap steel. As she wryly notes, sometimes your hometown is a state of mind; “I wanted to run away as fast as I could get, no matter where I’ve been, I can’t escape who I am.”

“River” is her attempt to emulate the late Leon Russell’s epochal “A Song For You.” Expansive yet intimate, the song is anchored by cascading guitar riffs, lowing cello, swooping lap steel, pliant piano, somber bass and chunky percussion. It’s Patty’s melismatic vocals, vulnerable one minute, indominable the next, that lifts this song to the stratosphere. She probably has someone else in mind, but she could just as easily be talking about herself; “You don’t need to save her or teach her to behave/Just let her arms unwind, ever changing and undefined, she’s a river.”

Finally, “Luminous Places” is an aching ballad that blends finger-picked filigrees, sparkly piano and mournful cello. The lyrics explore the fragility of life and the inevitability of defeat, bookended by incandescent piano and elevated, as always, by Patty’s patented Happy/sad delivery.

Two tracks, “What Now” and “Coins” include some vocal assists from Robert Plant. The former asks three simple questions; “Where to, what next, what now?” The latter is cloaked by swirly arpeggios; cryptic lyrics give no quarter as the erstwhile Golden God shades her rough-hewn vocals with his own davening style.

The album’s final two songs seem to revisit their relationship. “What I Remember” is stripped down to billowy Spanish guitar and Patty’s plaintive vocals. Her recollection adds a soupcon of sentiment; “Here’s what I remember, it was really that tender, the day I gave my heart away, the day that I surrendered.” The 13 song set closes with “Just The Same;” an aching post-mortem, just Patty on piano pouring out her heart. Here, she makes peace with the past; “Nothing could ever make me love you less, though I confess I’ve tried and wished I could, made of stardust and loneliness, and so many things I’ve never understood/I told myself we were not the same, that I would rise and rise and never fall, I told myself we were not the same, but we’re just the same after all.” It’s an evocative end to brilliant record.

When Patty Griffin sings, it cuts to your very soul. If she sounds sad, you’re sad. When she seems exhilarated, you are too. Her voice is a force of nature that demands your full attention. You can’t resist her, but why would you try?