By Eleni P. Austin

Punk Rock exploded in Great Britain back in 1977. The Damned were the first to make a record, while The Sex Pistols got all the ink and media attention, but for my money, the Class Of 1977, begins and ends with the Holy Triumvirate of The Clash, Elvis Costello and The Jam.

Maybe it’s because all three acts judiciously used Punk as a springboard to explore more complex and exotic musical genres. Perhaps, that’s why songs like “Career Opportunities,” Watching The Detectives” and “In The City” continue to resonate today. Sadly, Clash visionary Joe Strummer succumbed to heart failure a couple of days before Christmas in 2002. But Elvis and Jam front-man Paul Weller have continued to make vital and compelling music for nearly half a century. (Holy, shit, I’m old).

Paul Weller formed the earliest version of the Jam in 1972. Born in 1958, he grew up in Woking, the son of John, a taxi driver and Ann, a homemaker. He displayed an affinity for music as a kid. The Beatles, The Who and The Small Faces were early obsessions, and that music motivated him to seek out his idols’ musical touchstones. Thus, he became a full-time disciple of Motown, Stax-Volt, Curtis Mayfield, the Blues and Northern Soul.

He was just 14 when he convinced his best mates, Steve Brookes and Dave Waller, to start up a band. The line-up was complete when they recruited drummer Rick Butler. Paul’s dad agreed to be their manager and the nascent combo made their bones playing at the different working man clubs in Woking. When Steve and Dave decided to move on, bassist Bruce Foxton was recruited, cementing The Jam’s iconic three-piece configuration.

Gigging constantly, they began making a name for themselves. The Clash were so impressed they tapped The Jam to be the opening act on their White Riot tour. That exposure led to a deal with Polydor Records. Their debut, In The City, arrived in 1977. Paul’s lyrics articulated the angst and ennui that had British youth in its grip, perfectly capturing the zeitgeist of the times. While his trenchant melodies touched on the snarly and simplistic primitivism that defined Punk, he also managed to echo the sharp economy of British Invasion forefathers like Pete Townshend and The Kinks’ Ray Davies. Quite by accident, The Jam’s songs became the soundtrack to the Mod Revival of the late ‘70s.

For the next five years, over the course of six magnificent albums, The Jam topped the charts in the U.K., achieving massive critical and commercial success- a feat they never replicated in the U.S. By 1982, one of their final singles, the Motown-esque working-class anthem “A Town Called Malice,” finally received airplay on mainstream radio in America. But it was a pyrrhic victory, Paul was ready for new challenges. The Jam broke up and he immediately launched a new project with Mick Talbot, the sophisto-Soul two-piece he christened The Style Council.

Style Council allowed Paul to flex different musical muscles, integrating Jazz and ‘60s Soul his melodies. This new music presaged a hybrid sound that was hugely successful in the U.K. for up-and-coming artists like Everything But The Girl and Sade. Lyrically, he expounded on his Leftist politics and aimed withering critiques at Margaret Thatcher, the rise of racism and repent unemployment.

Style Council’s debut, Café Bleu (retitled and re-sequenced as My Everchanging Moods in America) arrived in 1984 and scored modest hits here with the title-track and “You’re The Best Thing.” Like The Jam, Style Council lasted about five years, give or take, folding at the end of the ‘80s. Following a couple years of well-deserved family time, Paul jump-started his solo career in 1992.

His eponymous debut arrived that year and it was a revelation. Somehow, he distilled his Punk/Pop, Jazz and Soul influences into one heady brew. He immediately made up for lost time, releasing albums like Wildwood, Stanley Road and Heavy Soul at a furious clip.

His music remained concise and economical, but managed to incorporate elements of Folk, Funk and Psychedelia into his ever-expanding sound. Just as Pete Townshend served as an artistic beacon for him during the Jam era, suddenly, Paul was being venerated by Brit-Pop superstars like Oasis, Blur and Ocean Colour Scene. Their reverence earned him the affectionate sobriquet The Modfather.

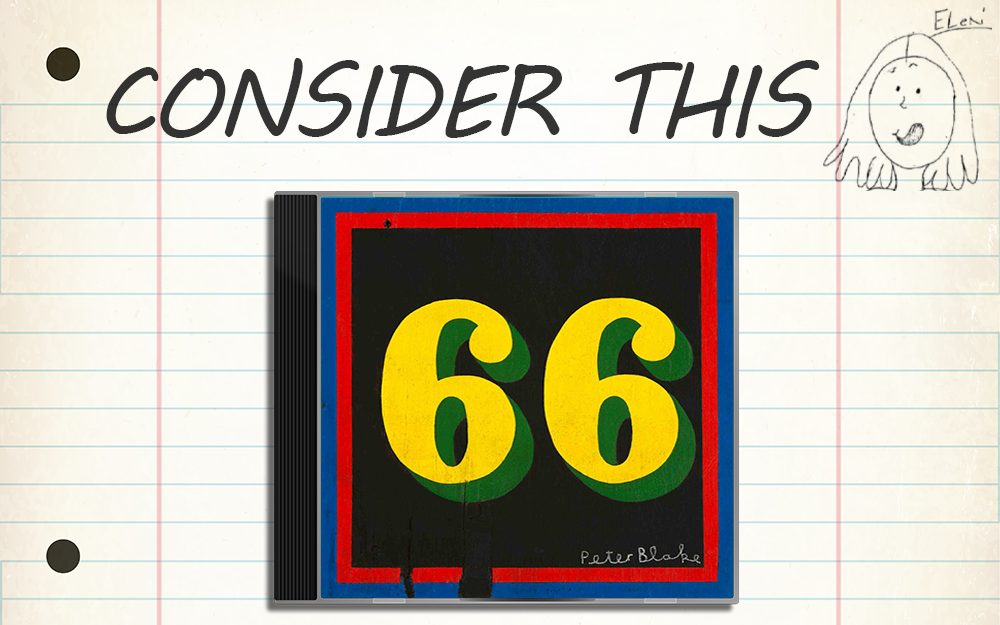

All told, Paul has released 16 solo albums, five live efforts and myriad compilations. Both The Jam and The Style Council have been the subjects of lovingly curated documentary films (About The Young Idea and Long Hot Summers: The Story Of The Style Council, respectively). Now he has returned with his latest album, 66, rather fittingly released just ahead of his 66th birthday.

The record gently kicks into gear with “Ship Of Fools.” A breezy slice of finger-popping cool, links up feathery guitars, flickering bass lines, ticklish keys and nimble vibraphone to a snappy backbeat. Paul’s nonchalant croon wraps around an ichthyic analogy that suggests sometimes it’s better to swim against the tide: “Oh boy! These high seas can be cruel, when you’re trying to find your way, and girl, that man of war’s a fool, I wouldn’t want to follow him anywhere.” On the break, a pastoral flute solo lattices rippling piano notes, coquettish vibes and a woozy horn section.

For this record, Paul has shared songwriting duties with old pals and musical acolytes alike, but three compositions are wholly his own. “Flying Fish” extends the aquatic metaphor, well, sorta. But that’s where the similarities to “Ship Of Fools” begin and end. Here, the melody, instrumentation and arrangement cycle through a potent combo-platter of flavors and textures. As laser-focused synths dart through the mix, Mini-Moog, Mellotron and flinty organ notes swivel and sway, creating a sound that lands somewhere between Electronica and creamy Philly Soul. Drums gather speed just ahead of the chorus locking into a four-on-the-floor groove. Stream-of-conscious lyrics orbit an astral plane: “Stream the shit out of a dream, caught up in the thread of plots we’ll soon forget, so I look around and I hear that sound, as a million stars lift me up so far, and I wonder why as I look in the sky how such fine fish can end up like this.” As the song winds down, guitars sting and shang-a-lang, offering up a surprisingly brawny coda.

Then there’s “Sleepy Hollow,” which is powered by bendy electric guitar riffs, sinewy bass lines, sylvan flute, a frisky horn section and a galumphing beat. Lyrics offer sentiments that might have felt like anathema to the garrulous frontman of The Jam: a cryptic and slightly tender appreciation for a life well-lived: “Dreamland in the mirror, dawn seems so far, I stop to consider, and I’ll thank it all, the river and the road, for showing me the way home.” A swoopy flute solo (which wouldn’t seem out of place on a circa 1972 Afterschool Special), glides around percolating vibraphone on the break, briefly joined a plangent saxophone solo.

Conversely, “I Woke Up” conjures up one of those bewildering dreamscapes we shake ourselves awake from. Swoony strings, strummy guitars, shivery bass and a slipstitch beat cocoons the melody in a shimmering arrangement. That false sense of security is shattered as lyrics find him unmoored: “I woke up and everything had changed, no, nothing felt the same, wearing someone else’s shoes, I found in bins around the town, I’ve been walking round and round for a clue/Standing on the edge of a mighty ocean waiting for the tide to roll and within this realm of constant motion, I’m try’na find my role in it all, when I woke up.” Cascading arpeggios spill over plaintive lap steel and willowy strings on the break.

On a record that is stacked with superlative tracks, three stand out from the pack, lining up back-to-back. “Nothing,” is truly something to behold. Like the opening cut, this one is a collaboration between Paul, Graham McPherson (better known as “Suggs,” the frontman for one England’s premier Ska bands, Madness), as well as Andrew Chalk. Muted keys connect with slivery guitar, tensile bass and a kick-drum beat. The arrangement splits the difference between languid Jazz and lush ‘70s Soul. Flugelhorns meander and Paul unspools his most guileless love song since 1995’s “You Do Something To Me.” Lyrics recall humbler beginnings: “Nothing forged our love out of nothing, because it was only by having nothing, we were able to realize we needed nothing else but each other.” A Moog solo on the break echoes classic antecedents like Donna Summer’s “I Feel Love” and Pink Floyd’s “Wish You Were Here.”

Meanwhile, on the minor key masterpiece “My Best Friend’s Coat,” a tangle of carousel keys, anchored by Casio CZI, Roland Juno 6, Solina, Ondes Martenot, Hammond organ, celeste and harpsichord cloak plangent guitar, roiling bass and a fluttery beat. Co-written with Christophe Vaillant (sonic architect of the French quintet Le SuperHomard), the ethereal arrangement and airy melody softens the blows of Noir-ish lyrics like “In the depths of despair, I took another drink, it soothed my mind and helped me to think of all the places I’ve never been, down by the river, in souless penury, even the sky wouldn’t look at me, I had no point, I had no reason.” There’s a gossamer grace to this roundelay that belies the lyrics’ sad-sack sentiment.

Finally, “Rise Up Singing” is a collaboration between Paul, Miles Copeland and Blow Monkeys leader Dr. Robert, picks up the Soulfully socially conscious gauntlet laid down by long-gone brothers in arms like Curtis Mayfield, Barry White and Bobby Womack. There’s a buttery elegance to an arrangement of shimmery strings, chunky guitar riffs, pliant piano, rubbery bass lines, syncopated horns and a propulsive beat. Anthemic and elegiac in all the right ways, cogent lyrics persuade us to lay down our burdens: “When you’re coming home in the evening, leave your bags and let it lie, you just carry on believing, don’t let that feeling die/Rise up singing to the sky, feel free rising up and high, so loud it’s gonna make you cry, so glad I opened my eyes.” It’s a potent message for these dark days.

Although the mood of this record is mostly mellow, the action ratchets on “Jumble Queen” and “Soul Wandering.” The former, co-written by Oasis icon Noel Gallagher, is a Glam-tastic basher that weds spiky guitars, staccato horns, spidery bass and shuddery synths to a stuttery beat. Paul’s clipped vocal delivery matches the lyrics’ bitter kiss-off: “Just like the bullet I’m flying free, I see the future looking back at me, and while you’re crying over what has been, I’ll sing this song to the Jumble Queen.” A snaky solo sidewinds through the break with venomous aplomb.

The latter is a full-throttle Soul-Rocker that juxtaposes slashing power chords, slinky acoustic riffs, angular bass lines and a crackling backbeat with a wash of Hammond organ and Wurlitzer colors. Written with Bobby Gillespie of Primal Scream, lyrics search for grace. Brooklyn Soul collective Say She She join Paul on the shout-it-out chorus: “And I want to believe in something greater than me, and I’m humbled by the majesty of the sea, and the stars, and your love, soul wandering, still searching.” Cheerful flugelhorn runs dot the margins, injecting a bit of hope into the proceedings. Swirly keys collide with skronky guitars on break as plush horns sync up and go for baroque. Then this tour de force powers down on a dime.

Other interesting tracks include the courtly “Glimpses Of You” and the blurred and blissed out “In Full Flight.” The album closes with the moodily magnificent “Burn Out.” The phased instrumentation mirrors the lyrical lethergy: “We’re going nowhere.” But a smoky saxophone solo rises from ashes, exhaling like a post-coital cigarette. It’s a hypnotic finish to a beautiful record.

Paul was joined by a plethora of pals on this album, including Steve Brookes, Jacko Peake, Steve Craddock, Richard Hawley, Dr. Robert, Ben Gordelier, Erland Cooper, Le SuperHomard and his daughter, Leah Weller. At this point in his career, he would be well within his rights to rest on his laurels. Instead, Paul consistently challenges himself and his audience. 66 evokes comparisons to giants like Burt Bacharach, Curtis Mayfield, Bobby Womack and David Bowie. There’s a ferocity and passion to this music that can’t be denied. Simply put, The Modfather never gets old.