By Heidi Simmons

There’s a stretch west of Indian Canyon Avenue in the direction of highway 62 on Dillon Road where residential life quickly drops away and the scenic desert expanse becomes industrialized with high intensity power lines, solar farms and wind turbines. Here desert resources are used to generate energy.

Off this barren, quiet thoroughfare, washed with sand from the last summer storm, is a new $900 million power plant.

A freshly engineered blacktop road with drainage and curbs leads north toward the older “daisy fields,” the affectionate term for wind farms. Weathered windmill parts and blades are stacked and strewn behind new chain link fence with three tiers of barbed wire. Rather than in neat rows, the aged and dated wind turbines here seem randomly planted on uneven desert terrain, gullies and hills.

Further back on Melissa Lane, set level and center of 37 acres, is the CPV Sentinel Energy Plant. Unlike the surrounding spindly windmills, sparse and barely turning, this is a mighty collection of tightly organized, gargantuan structures humming with the production of energy, capable of generating 800 megawatts of electricity. Enough power to light up the homes of the CV.

Competitive Power Ventures, Inc. (CPV) along with GE Financial Services and Diamond Generating Corporation, completed construction of the plant and was on-line for service May 6. It is what the industry calls a “peaker plant,” also known as a simple-cycle plant. The facility is designed to start-up quickly to meet the imminent demand for energy when the electric grid cannot meet the supply — when energy requirements are at their highest.

“We can be up and running in ten minutes,” said Mark McDaniels, Vice President of CPV. “We typically only operate during periods of peak demand for electricity. Our quick start ability allows us to supply power to the electrical grid system when needed.”

At the site, behind a monitored electronic gate, four massive water tanks dominate the welcome. They look freshly painted, clean and tidy. Each is boldly marked with the contents: RAW WATER TANK Capacity: 2,300,000 gallons; two smaller tanks, DEMINERALIZED WATER Capacity: 364,000 Gallons and WASTE WATER TANK Capacity: 1,350,000 Gallons. They stand close together like a well-groomed family — the kids in between mom and dad.

Although these tanks greet you at the gate, water is only a supporting factor in the production of energy at this state-of-the-art plant. CPV is a natural gas powered electric generating facility. It burns 9000 BTUs (British Thermal Units) to make one-kilowatt hour of electricity.

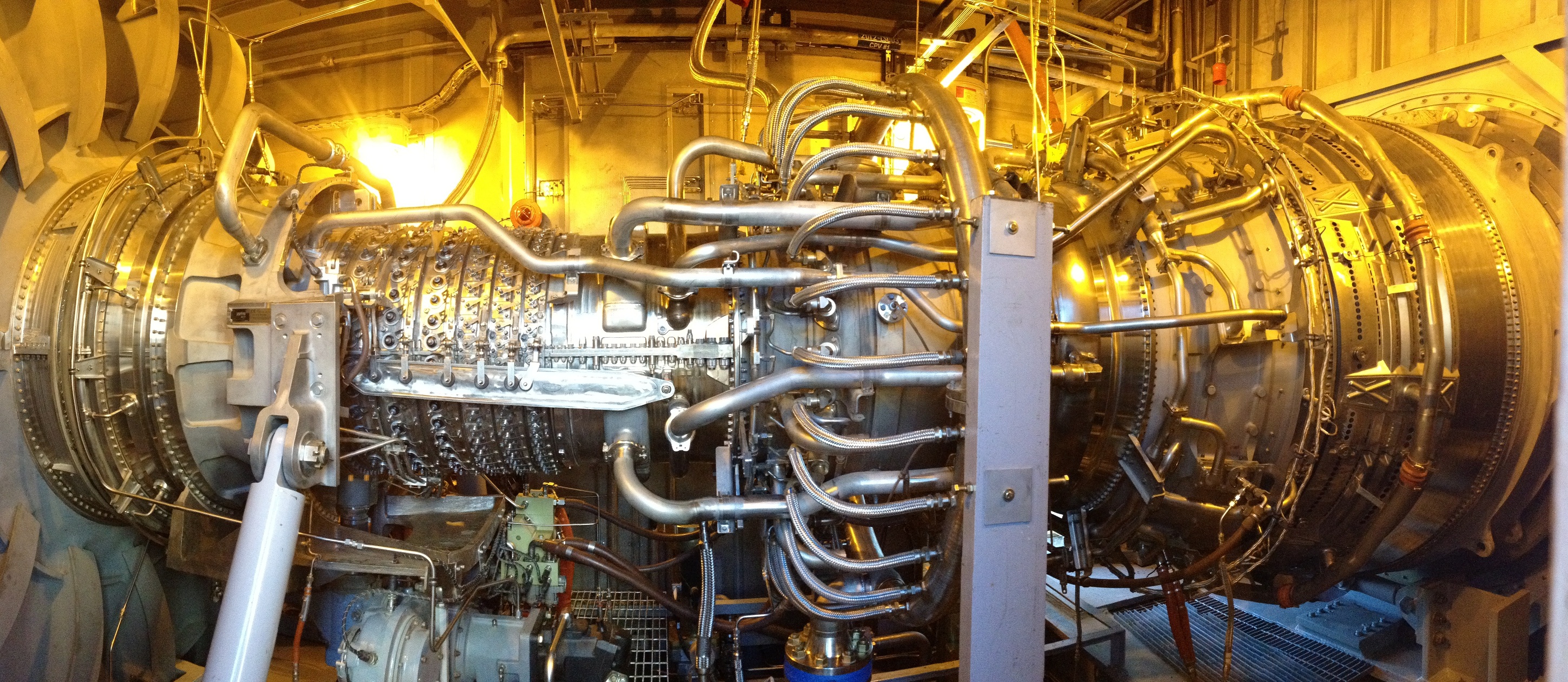

The power plant consists of eight 100-megawatt natural gas powered electric generators. Each generator is accompanied with an array of stainless steel pipes that neatly bend and connect to other over-sized equipment. Matching and uniformed, large and small parts combine to make a complete unit. A baffled and cantilevered air intake, which functions similarly to a swamp cooler, stands three stories tall. There’s a robust 90-foot emissions stack with a “crow’s nest” and a water-cooling tower like a giant Jack-In-The-Box — but instead of a clown being released, it’s water vapor. Put all together, the equipment is imposing, handsome yet somehow humble.

“The system operates similar to that of a gas powered car,” said McDaniels. “Filtered air goes in, mixes with the fuel, is ignited and generates heat, which is then converted into torque that drives the shaft and spins the generator that creates power.” According to McDaniels CPV is much cleaner than a car and more efficient. This small-scale example is an effective model of how CPV’s system works. It is a simplified understanding of what alchemy is really taking place to produce the magic of electricity.

The GE LMS 100 aeroderivative combustion turbines that produce the power are similar to what hangs on the wings of 747 jet airliners. They look like the engines used for Pod Races at Mos Espa Arena. In fact, the planet Tatooine would envy this facility.

In a long, perfectly aligned row, the identical units are numbered one through eight — the octuplets too new to display any individual personality. A thick layer of simple grey rock covers the essential grounds of the plant, kept in place by precise blacktop roads and connecting footpaths. Like a Zen garden, there is simple beauty to this otherworldly facility.

On the day of my visit, although it was barely 100 degrees, overcast with a slight breeze, all eight siblings were working. Here’s why: As a peaker plant, CPV comes on line only after all other energy sources are in use, including renewables. Or like this day, when renewable energy is not available to contribute to the grid. So when it is the hottest time of the day and there is no breeze or sunshine, CPV can quickly generate power and supply it to the grid adding as much power as needed up to 800 megawatts. When CPV’s energy is no longer required and the demand met, it can just as quickly shut down. McDaniels characterizes the plant as “nimble.”

According to California Independent Systems Operator (Cal ISO), a nonprofit public benefit corporation, Californians use over 300 million megawatt-hours of electricity a year. Here’s a way to think about it: A watt is a unit of power, or energy per unit time. It is the rate at which energy is being used. If you are reading the CVW in a room with ten, 100-watt light bulbs on, and it takes you an hour, that’s 1000 watts or one-kilowatt hour. Electric companies bill in kilowatt hours (kWh). 1000 kilowatts (ten good folks each reading CVW in different rooms, with ten 100 watt light bulbs) is equal to one-megawatt hour. The average household uses10,000 kilowatt-hours of electricity each year or ten-megawatts.

A major supplier of electricity to Southern California was San Clemente’s nuclear power plant at San Onofre. It is no longer operating and has been permanently closed by Southern California Edison.

San Onofre was a “base load” facility, meaning it ran nonstop everyday of the week all year long generating 2000 megawatts each hour. Base load plants carry the biggest burden in producing constant power, typically at the cheapest rates. As demand increases, so does the price of power.

Then there are “intermediate load” plants that may produce energy for days, a week or even a month, filling the gaps between expected demands above the base load facilities. These plants take several hours to start and shut down. When base load and intermediate load energy is still not enough, peaker plants make up the difference. In short notice, peakers can contribute a reliable, safe and secure power supply.

For several reasons, this western edge of the CV is ideal for energy production. There is the obvious — open space, wind, sunshine and water. But the other essential component is transmission. The electricity must be added to the “electron superhighway” — the power gird in order to reach 30 million users. Power is useless if you can’t get it where it’s needed.

CPV Sentinel is located between North Palm Springs and Desert Hot Springs in Riverside County. The peaker plant is only 700 feet from the Devers Substation where energy is stepped-up to the right voltage for transmission. Southern California Edison owns Devers. High-voltage transmission lines and a natural gas pipeline run parallel to Interstate10 and are within a few miles of the site. The less distance electricity has to travel, the more efficient.

For most of the Coachella Valley, no matter the source of the power — wind, solar, base, intermediate or peaker generated — it all goes into the grid for distribution and use. And it can be used anywhere. Once the energy is moved into the system, the responsibility of the power plant is done. Just because the CV has generating facilities, it does not mean exclusive use in the CV. If you were hoping that all the power generating facilities here would stop our rolling brown or black outs, know they are doing their part to supply the grid, but they have nothing to do with getting electricity to your home or business.

The exception is the Imperial Irrigation District (IID), which controls more than 1100 megawatts of energy derived from their own diverse resource portfolio. They serve 145,000 customers in the Imperial Valley, parts of Riverside County (that include the CV’s East Valley), and parts of the San Diego County. IID Energy is a consumer-owned utility.

But private or public, Cal ISO manages the grid. Everyday they estimate the demand, and analyze the supply. They serve as a market — a one-stop shop for electricity that ensures transparency and equal access. They keep the power flowing.

All of the energy business is regulated and CPV Sentinel is closely monitored. As a peaker plant, it can only operate 30 percent of the time. They are allowed 300 starts per unit, per year. That’s 2500 total hours. Whether the plant is operating or not, emissions from the site are monitored 24 hours a day at the site and by the South Coast Air Quality Management District electronically. CPV’s permit conditions allow for fine particulate material (PM) of 2.5 the result of burning a fossil fuel. “During my career in the power-generation industry, limits have fallen as emissions reduction technology has improved,” said McDaniels, who has been in the business for 30 years.

The plant has zero liquid discharge (ZLD). Filling its well from the Mission Creek Aquifer, it uses and reuses its water, requiring 1100 acre-feet per year. Desert Water Agency has partnered with CPV and, through water purchases and import to the valley, CPV has already replenished the aquifer with more water than the plant is expected to use in ten years of operation.

CPV Sentinel funded a recycle water pipeline to a local golf course and infrastructure upgrades that are expected to conserve more water than the site will use on an annual basis. They paid for a smart irrigation controller program providing 4,800 DWA customers with free smart irrigation control systems installed at no cost. With conservation and replenishment, there has been no sign of water draw-down from the aquifer.

CPV has a full time staff of only14, with two at the station 24/7 in a rotating shift schedule. There is a simplicity to the command center. It is a large open room, with plain white walls and folding tables. Hard hats and reflective vests hang by the door. The room is bright with windows; the computer screen is no bigger or elaborate than a home desktop versions. The interface uses graphics that are easy to read and use. Periodically, an automated female voice from Cal ISO gives instructions to increase or decrease power production. There is a mellow vibe at the facility. Those working there appear calm, competent, focused and knowledgeable.

August 1st begins a ten-year contract where CPV will exclusively deliver power to the gird for Southern California Edison. All the restrictions will be maintained. This year CPV Sentinel will pay $8 million in property tax. They are regular contributors to local organizations and are working at being good neighbors and responsible members of the community.

All energy producers are subject to state mandates regarding renewable sources. It is a directive they respect and take seriously. McDaniels clearly loves the energy business. He is enthusiastic, optimistic and realistic. McDaniels has worked with nuclear, geothermal, wind, ethanol and biodiesel fuel sources. “With existing technology you have to have plants like this. I like the idea of more distributive generation and a lot more solar on every rooftop. But for now, there’s no way around base, intermediate and peaking units to reliably supply power to our electric grid,” said McDaniels. Obviously we too love electricity, and CPV plays an important part in meeting the demand.