By Heidi Simmons

—–

On The Move

by Oliver Sacks

Memoir

—–

It seems the term “autobiography” has been replaced by “memoir.” And for good reason: Sharing personal experiences is far more potent than simply recounting one’s life.

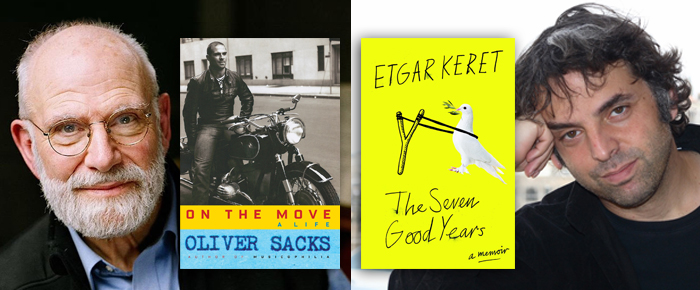

In Oliver Sack’s On The Move (Alfred Knopf, 416 pages) and Etgar Keret’s The Seven Good Years (Riverhead Books, 192 pages) literary men share their passion for narrative through the highs and lows of their own life story.

On The Move is the personal story of the physician and author behind the wonderful non-fiction work Awakenings, The Man Who Mistook His Wife for a Hat and ten other amazing books about human beings and the complicated nature of the brain and perception.

Sacks, who recently turned 82, reveals his love for science and writing. He begins with his obsession for motorcycles. Sent away to boarding school during the war in England, motorbikes represented freedom and power. The book is constructed with the big moves in his life and significant trips that include America, Israel, Amsterdam and Norway.

A brilliant child by all accounts, Sacks never boasts or brags. He simply puts his life in context to the world he so acutely observes. He was a curious child growing up in a household where he was encouraged to explore his interests.

Sacks’ parents were both physicians; his mother a surgeon and father a general practitioner who worked from home. Sacks was the youngest of four boys. His two eldest brothers became medical doctors as well. The other, just as brilliant, became schizophrenic.

Sacks shares the difficulty of being gay in England, where homosexuality was illegal. His mother called him as an abomination. Indeed, the book includes his search for love, but mainly stays around his maturation into adulthood as he pursued a career as a prominent neurologist. During this time he discovered his ability to write about his patients and experience. He includes the catalyst and circumstances for many of the books he authored.

Ultimately, the memoir is his discovery that he is an author first and that writing is his gift and greatest pleasure — perhaps even an addiction. Using journals he kept from the age of 14 and letters he wrote to friends and family, and the return responses, he reconstructs important moments in his life. “I find these old letters a great treasure, a corrective to the deceits of memory and fantasy.”

With easy prose and a generous spirit, Sacks doles out his life like the proverbial open book. Unashamed and fearless, he shares his passion for scientific discovery, the human species and the joy of being able to write about it.

—–

The Seven Good Years

by Etgar Keret

Memoir

—–

The Seven Good Years is Keret’s account of life beginning with the birth of his son and ending with the death of his much beloved father. It’s all set with the backdrop of a turbulent Israel.

With short, witty chapters that cover a seven-year period, Keret shares a world in conflict – metaphorically, personally and literally. It begins with his wife giving birth as doctors run to help victims of a terrorist attack.

A first generation Israeli, Keret’s parents are Polish immigrants who survived the war. His mother was the only survivor in her family. His father’s family was carried out of a hiding place by the Russians. The hidey-hole was so small the family’s muscles had atrophied.

Keret’s sister marries into a Jewish Orthodox family and is considered “wed and dead” since she can no longer associate with her secular family. During a missile attack, Keret’s “nervous” seven-year-old son becomes part of “pastrami sandwich” between his folks when the family takes cover in a ditch — a game they hope not to play again.

There are lighter moments. When Keret attends a writer’s festival in Germany, he fights with a guy who he thinks is insulting him as a Jew, when in fact, he has misunderstood the language. The guy was upset about a car parked illegally.

My favorite story is in “Year Four” called “Bombs Away.” When Keret hears that Iranian President Ahmadinejad wants to annihilate Israel, he and his wife stop worrying about upkeep on their house. He only sprays cockroaches because they’ll survive the nuclear attack.

They spend their money and run up debt since life as they know it may soon end. But in a dream, Ahmadinejad comes to Keret, hugs him and kisses both cheeks and whispers in perfect Yiddish, “My brother, I love you.” The next day Keret fixes the plumbing and cleans the house.

All the stories over the seven years are charming tales of life in an uncertain world. Keret has a beautiful way with narrative that is filled with humanity and insight. As a father, he paints a picture of a tenuous lifestyle. The subtext is desperate — he only wants peace and a better life for his son, family and country.

I enjoyed both these books and found them to be complimentary companion pieces. They made me laugh and brought me close to tears.

Each author tells of sitting Shiva after the death of a parent. Although both Sacks and Keret are secular Jews, they are deeply moved by this act with their siblings and it changes them as human beings. They are able to better reflect on their own lives.

During his mandatory service with the Israeli Army, Keret wrote his first short story. When he shared it with his brother, he realized he had transmitted his feelings from his mind into his brother’s mind. “I had discovered magic that I needed to help me survive…”

Author Sacks concludes his book: “Over a lifetime, I have written millions of words, but the act of writing seems as fresh, and as much fun as when I started it nearly seventy years ago.”

Sacks and Keret thrive by writing about the mystery of life. Whether an entire life or just a snapshot, both authors embrace powerful memories and bring universal meaning to the graceful words they put on the page.