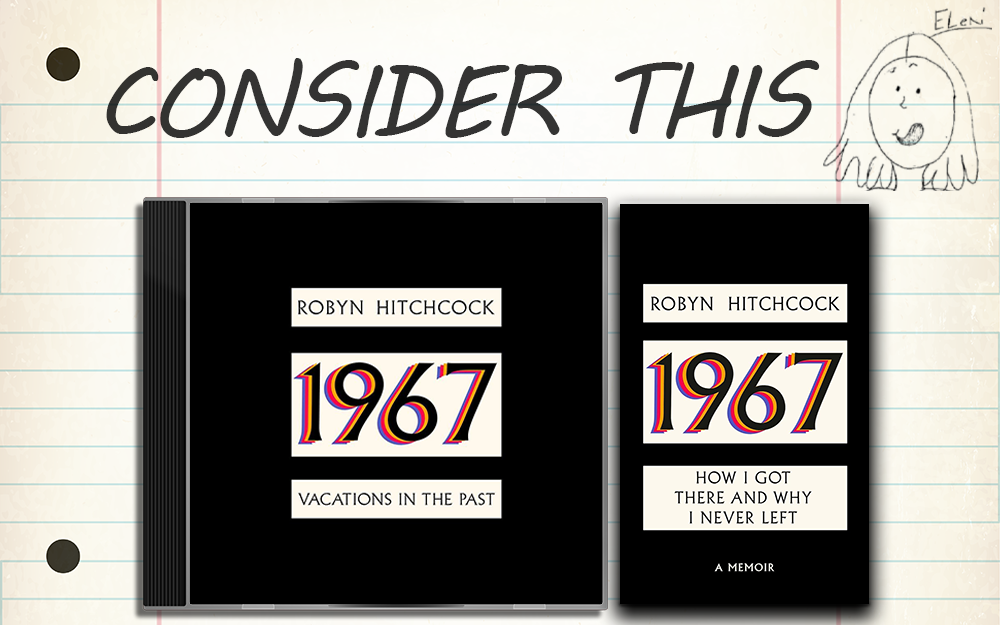

“1967” (Akashic Books) and “1967: Vacations In The Past” (Tiny Ghost Records)

By Eleni P. Austin

Robyn Hitchcock has just written his memoir. Rather than offer up a pocket history of his 71 years on earth, he has opted to concentrate on one pivotal year, 1967.

But that isn’t too surprising. Throughout his music career, he’s always managed to color outside the lines. The idiosyncratic singer-songwriter was born in London, England in 1953. His father, Raymond, found belated success as a novelist. His best-known book is Percy, wherein a man receives a penis transplant and goes in search of it’s donor. (Clearly the apple didn’t fall far from the tree).

Robyn attended boarding school at the height of the Swinging ‘60s. During those heady days he received a Pop music education, thanks to the BBC and older, astute classmates, that continued through college. Once he was done matriculating, he knew he wanted to make music his career.

He started by busking in Cambridge, plying his trade on street corners. Soon enough, he was playing in cover bands. Although he had begun writing his own songs at 16, it took a few years to build up enough confidence to play them for other people. By age 23, he had formed The Soft Boys. Their sound was a sharp amalgam of Psychedelia, buzzy Punk energy and jangly Folk-Pop. Despite the fact that critical acclaim was nearly unanimous, they never caught on commercially. But, much like the U.S. band, Big Star, they wound up influencing a clutch of great ‘80s bands like R.E.M., Replacements and a loose confederation of groups in L.A. known as The Paisley Underground.

After The Soft Boys broke up Robyn went solo in 1981. His first three albums displayed his quirky, slightly surreal sense of humor. His next three efforts featured a new backing band, The Egyptians.

As with the Soft Boys, critical praise was effusive, and major labels began to take notice, but the general public were slower to catch on. Once he signed with A&M Records in the late ‘80s, he actually scored a bona fide hit single in with “Balloon Man,” off the 1988 album, Globe Of Frogs.

Over the next three decades, he made music at a furious clip, toggling between solo efforts, Soft Boys reunions, collaborations with Americana stalwarts Gillian Welch and Dave Rawlings, The Venus 3 (which included Peter Buck from R.E.M., and Young Fresh Fellows front-man Scott McCaughey), as well as his partner Emma Swift and a project with ex-XTC mastermind Andy Partridge.

All told, he’s released three Soft Boys albums, 12 solo records, four with The Egyptians, three with Venus 3, plus 11 compilations, seven live albums and four “Best Of” collections. Now he has written a memoir, 1967, which charts the most pivotal year of his life, and he’s also released a companion record of sorts, 1967: Vacations In The Past.

The book is a marvel, dropping our adolescent hero into boarding school in early 1966. He slowly adjusts, learning an arcane form of preparatory speak dubbed “Notions,” only to understand it is forbidden to use in academic study. He wryly notes “On the whole, I get off lightly, I’m not beaten up, sodomized or ritually humiliated by the other inmates. Nobody sticks my head down the toilet bowl, nor am I stripped and mocked. Perhaps my parents aren’t getting their money’s worth.” He acclimates eventually, this coincides with his new addiction, music. Of course, The Beatles are the gateway drug.

By the time 1967 dawns, he is completely besotted with Bob Dylan. The record player in the common area is now his axis. Music is played, debates ensue: Beach Boys vs. Jimi Hendrix, self-doubt creeps in-is it okay to like catchy Monkees songs even though they’re supposed to be a manufactured Pop band? In short order his mind in blown by Hendrix, Pink Floyd, The Kinks, Procol Harum and The Incredible String Band.

Although Robyn never experimented with drugs, he attended plenty of local “Happenings,” spearheaded by older guys like future Roxy Music/Electronica pioneer Brian Eno. Classmates are divided into “two opposing strands in our Academy: the meatheads and the groovers. The meatheads are into sports, alcohol, talking about sex and The Beach Boys. The groovers favor beat poetry, Jazz and incense sticks; they’re also more like to enjoy Bob Dylan, and their compass points to hashish.” For Robyn, Dylan remains an oracle.

1967 is also the year he picked up the guitar for the first time. He has some formal lessons but makes more progress by dropping the needle on his favorite records and plucking along until he’s figured out chord sequences. The book is packed with comical anecdotes like accidently skinny-dipping with a ginger-haired instructor, speculating about the erstwhile love life of the House Matron and a sophisticated Art Master whose housekeeper introduces young Robyn to culinary delights beyond his steady diet of cheese and tomato sandwiches.

Along the way, he responds to the dramatic melancholy of Procol Harum as well as the urgent and demented sounds of Pink Floyd, under Syd Barrett’s aegis. Even as a teen, he grasps how certain songs succeed because “sadness is the shadow of beauty.”

His droll wit and skewed perspective is present throughout the book, and it’s clear this epoch remains close to his heart. In a recent interview, he drily observed that his “compass shifted (that year) from mom and dad, sisters, au pair girls and grandma, and moved around to Bob Dylan-very like a relationship with God.” He went on to say “That was the most vivid time of my life, I was going through puberty, and I was in a world that was changing as fast as I was. So for about 18 months, the world and I were keeping pace. Then the world raced ahead.” 1967 is equal parts sweet and sardonic, offering up a mordant portrait of the artist as a young man. Rich in detail, it navigates the rocky shoals of adolescence with humor, empathy and grace.

To accompany the memoir, Robyn has recorded a companion CD, 1967: Vacations In The Past. The 12-song set features pared down renditions of Robyn’s favorite touchstones from that era. It opens with the one-two punch of Procol Harum’s “Whiter Shade Of Pale” and The Small Faces’ “Itchycoo Park.”

It’s a tart juxtaposition. The former blends sun-dappled guitars and plangent keys. There’s a mournful ache to this Bach-ified melody, as cryptic, elusive lyrics manage to hint at heartbreak and seduction, as well as Chaucer’s slightly ribald Miller’s Tale. The latter is a rollicking campfire sing-a-long powered by jangly guitar and swirly keys. Lyrically, getting high and touching the sky are the primary objective. Guitars flange and intertwine on the hallucinogenic outro.

Robyn, being Robyn, he slyly shies away from the big hits of period. Leaning in on the Paisley-pastoral ramble of The Move’s “I Can Hear The Grass Grow,” or Traffic’s wistful “No Face, No Name, No Number,” which is anchored by muted keys, finger-picked acoustic filigrees and his tortured vocals.

He actually recalibrates a few classics. Obviously, he could never match Jimi Hendrix’s wah-wah pyrotechnics, so “Burning Of The Midnight Lamp” is stripped-down to shuddery acoustic guitar and his quavery vocals. Scott McKenzie’s Summer Of Love anthem, “San Francisco (Be Sure To Wear Flowers In Your Hair),” is a slow and slurred meditation, fueled by menacing acoustic guitar, piquant sitar, along with reverse guitar and piano. Meanwhile, Robyn approaches the lunatic glee of Pink Floyd’s “See Emily Play” with restraint. His impish vocals wash over cantering acoustic riffs and skronky slide guitar.

The best tracks here split the difference between contemplative, playful and quick-witted. Although less ornate, he wraps gossamer guitars and liquid keys around The Kinks’ melancholy masterpiece, “Waterloo Sunset.” Tender vocals caress Ray Davies vivid imagery: “Dirty old river, must you keep flowing into the night, people so busy, make me feel dizzy, taxi light shines so bright, but I don’t need no friends long as I gaze on Waterloo sunset, I am in paradise.”

Tomorrow’s “My White Bicycle” was one of the first Psychedelic songs to include backward guitars (following the pioneering work of The Beatles’ “Tomorrow Never Knows” from 1966). Robyn’s version lattices stacked vocals across braided acoustic guitars, reverse piano and keening backwards guitar.

Scotland’s Incredible String Band straddled the line between Folk and Psychedelia and Robyn tackles their shambolic and slightly smart-ass “Way Back IN The 1960s,” Phased and dusted vocals ride roughshod atop thrumming acoustic and electric guitars. Sung from the perspective of a nonagenarian, lyrics wax rhapsodic about the good ol’ days: “There was one fellow singing in those days, and he was quite good and I mean to the say that, his name was Bob Dylan and I used to do gigs too, back before I made my first million.”

Robyn contributes one original. “Vacations In The Past” blurs cascading guitars, willowy sitar and plaintive piano. Lyrics pay homage to the halcyon days of his youth even as “I fumble for tomorrow, like an Octopus on speed, tentacles akimbo, my insatiable need for you my love.”

As much bandwidth as he receives in the book, it’s something of a surprise that Bob Dylan is M.I.A. is this lovingly curated collection. But the album closes with a piano-driven read of The Beatles’ cinematic “Day In The Life.” It’s a majestic finish to a sweet record.

Taken together, the book and the album illuminate Robyn’s annus mirabilis. That year was a gateway to, well, everything. The foibles and epiphanies came fast and furious. 1967 offers a snapshot of a time when everything seemed possible.