By Eleni P. Austin

Back in the ‘60s, Bob Dylan and the Beatles changed the face of Rock & Roll. Really, they were the first artists to write their own songs and craft albums. Before, performers were content to record a hit and hastily cobble together a few more songs that served as musical filler.

At the dawn of the ‘70s, the Beatles broke up and for Dylan, music took a back seat to family. It seemed like every time a male singer/songwriter recorded a debut he was hailed as “the new Dylan.” John Prine, Loudon Wainwright and Bruce Springsteen were all tagged with that appellation at the beginning of their careers. But no one was ever touted as the new Lennon & McCartney, that is, until the British band Squeeze arrived at the end of the “Me Decade.”

The legend goes that in 1973, Chris Difford stole 50 quid from his mother’s purse and placed an advert in a sweet shop looking for a guitarist for his (nonexistent) band. Glenn Tilbrook was the only person who answered the ad. The duo began writing songs together and added Jools Holland on keys, Paul Gunn on drums and Harry Kakouli on bass.

They cycled through a number of names before settling on Squeeze, after a poorly received Velvet Underground record that was released after Lou Reed exited the band. They began gigging around Depford, sharing stages with other up-and-comers like Dire Straits and Alternative TV. When they swapped out Paul Gunn for drummer Gilson Lavis, they solidified their sound.

Squeeze signed with A&M and, rather ironically, the label assigned ex-Velvet Underground founder John Cale to produce

their first album. Mysteriously, Cale wanted to name the album “Gay Guys,” and ultimately their collaboration was a mis-match.

The label agreed, Cale’s contributions were deemed uncommercial. A&M actually sent the band back into the studio to produce two songs themselves. When their self-titled debut arrived in 1978, the album’s only hits “Take Me, I’m Yours” and “Bang Bang” were both produced by the band.

Their next three efforts, Cool For Cats, ArgyBargy (wherein John Bentley replaced Harry Kakouli on bass), and East Side Story, released in 1979, 1980 and 1981, were watershed records for the band. The first two were produced by John Wood, and East Side… boasted production from simpatico tunesmith Elvis Costello.

All three records focused on the sharp songwriting prowess of Difford & Tilbrook. Songs like “Up The Junction” “Pulling Mussels (From The Shell)” and “Tempted” combined pithy (Lennon-esque) lyrics with sunny (McCartney-esque) melodies, all awash in the dayglow colors of New Wave.

East Side Story was particularly trenchant, a tour de force that dabbled in everything from Country to Psychedelia, to Pub Rock and Baroque Pop. It remains the band’s magnum opus.

The constant touring, writing and recording took its toll, and by 1982 the band was knackered. Unfortunately, their exhaustion showed. Their fifth album, Sweets From A Stranger, yielded a hit, “Black Coffee In Bed,” but the album suffered from the band’s lethargy. The overly synthesized instrumentation (de rigueur in the early ‘80s), didn’t help.

By the end of the year, Squeeze called it quits, releasing a greatest hits album, Singles-45’s And Under. It featured one new track, “Annie Get Your Gun,” which they performed on “Saturday Night Live.”

Two years later Difford and Tilbrook released a self-titled duo record that buried great songs beneath tepid ‘80s production values. It was a noble experiment that failed miserably, but it opened the door for a Squeeze reunion.

The remainder of the decade saw three Squeeze records, whimsically entitled Cosi Fan Tutti-Fruiti, Babylon And On and Frank. Babylon… was actually a bonafide hit in the U.S., the single, “Hourglass” peaked at #15 on the charts. The ‘90s saw the band release a series of serviceable, but not spectacular albums; Play, Some Fantastic Place, Ridiculous and Domino.

At the turn of the century, it seemed as though Squeeze was in the rearview mirror. Chris Difford released four solo albums and Glenn Tilbrook released six. Surprisingly, Squeeze hit the road in 2007 to promote a couple of new hits compilations. They would tour on and off for the next few years. They even re-recorded their old hits, challenging fans to “Spot The Difference.”

Touring is lucrative, but by sticking with the old hits the band seemed consigned to Oldies act status. (Even though it’s wildly disconcerting to categorize early ‘80s songs as “oldies”).

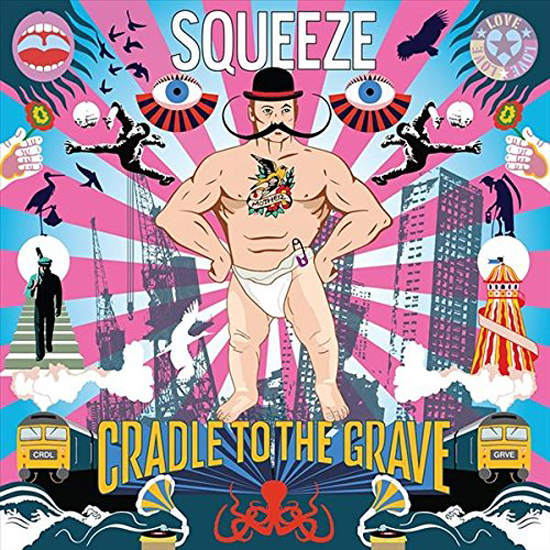

Difford and Tilbrook intended to collaborate on new music but nothing came together until the BBC asked them to write songs for an eight part TV series, Cradle To Grave. Based on comedian Danny Baker’s autobiography, “Going To Sea In A Sieve,” it takes place in South London, circa 1974. The result is Cradle To Grave, their first new music in 17 years and their 14th studio album.

Difford and Tilbrook intended to collaborate on new music but nothing came together until the BBC asked them to write songs for an eight part TV series, Cradle To Grave. Based on comedian Danny Baker’s autobiography, “Going To Sea In A Sieve,” it takes place in South London, circa 1974. The result is Cradle To Grave, their first new music in 17 years and their 14th studio album.

The record gets off to a rollicking start with the title track. Barrelhouse piano runs collide with a brisk and jaunty back-beat. The cogent lyrics vow to make the most of life; “They say time is of the essence, they say time will always tell, I wasted time in a constant panic as the Rome around me fell/And each moment that is stolen gives another time to breathe, in a life of turning pages/With the bit between my teeth.”

Four songs brilliantly limn the contrasting feelings of adventure and angst that accompany adolescence. “Only 15” is anchored by rippling, Big Easy-style piano chords, a stuttery rhythm, Moog fills and waspish guitar riffs. The lyrics paint a vivid picture of teenage make-out party; “the cheap warm drinks had begun to flow, the curtains were pulled and the lights were low.” But the kid’s post-coital bliss is high-jacked by thoughts of parental retribution for a missed curfew.

“Top Of The Form” captures the chronic disconnect of school days: “We had P.E. on Tuesdays and English on Wednesdays/School was a prison where I did my time.” Powered by Surf/Spy guitars, celeste, timpani, piano, organ and tinkling percussion, the slapdash melody belies the monotony of matriculation. It’s a stylistic mash-up: James Bond-meets-Bachelor-Pad Exotica -meets-Honky-Tonk Country, but it works beautifully.

Layered with cellos, violins, violas, double bass, Mini-Moog and handclap percussion, “Sunny” is positively “Eleanor Rigby-esque.” But instead of examining quiet lives of desperation, the lyrics offer a treatise on teenage epiphanies that closely mirror Difford and Tilbrook’s experiences. “My growing up would not be easy, going for long walks on the heath/Trying to play like Jimi Hendrix, behind my back and with my teeth.”

Finally, “Haywire” is very much in the tradition of the Who’s “Pictures Of Lily,” Elvis Costello’s “The Beat” and the Vapors’ “Turning Japanese.” Each one is a cheerful ode to onanism. Fueled by a stop-start rhythm in ¾ time, this countrified waltz is accented by celeste, piano, and high lonesome pedal steel.

The lyrics recall halcyon days of self-pleasure with clever couplets like “I’m thinking about the images my teenage-self enjoyed, those dangerous excursions took the man out of the boy/The women I encountered there became good friends and stuck/Together in the pages to see a teenage boy thunderstruck.”

Three tracks tackle less um, solitary forms of romance. Over pounding drums, frenetic space-age synths, jangly guitars, a manic harmonica solo, and a marauding ‘70s guitar-hero solo, “Honeytrap,” chronicles first love gone wrong. Kind of a sideways homage to the Kinks’ “Dedicated Follower of Fashion,” here the teenage swain has trouble choosing between love and a natty wardrobe.

“Nirvana” offers a withering account of a long-time marriage suffering from empty-nest syndrome. The breezy melody features a smorgasbord of instrumentation. A four- on-the-floor Disco beat, bloopy synths, fluid Philly-Soul strings, swirly piano notes and the kind of sitar-guitar licks pioneered by the Stylistics. All of that almost camouflages the bitter ennui of the lyrics. “Each day like the one before, their dreams evaporated as the weeks turned into years/The queasy feeling that they wanted more.”

“Open” is less dire; a joyful celebration of a late-in-life marriage. Propelled by shimmery guitar, celeste, organ, melodica and an urgent backbeat, the melody a slight call-back to one of an enduring Squeeze classic, “Pulling Mussels (From The Shell).”

Once again, the concise lyrics spell everything out in a few deftly turned phrases; “Standing in the picture with his family all around, proud to see their father finally put the anchor down/She had offered amnesty for a multitude of sins, through the stained glass window her love shone down on him.”

Other interesting tracks include the footballer’s reverie of “Beautiful Game” and the sunshiny summer idyll “Happy Days.” The album closes with the most reflective songs, “Everything” and “Snap, Crackle And Pop.”

The former feels rueful and autumnal, awash in sun-dappled guitar and keening Wurlitzer notes, looking for redemption after a lifetime of missteps. “What makes me happy, I wish I knew, I search for peace to fill my soul/And when I’ve hurt the ones I love, I dig myself a deeper hole.”

The latter feels like a jazzy benediction, pivoting from lissome Bacharach-y verses to a soulful, call-and-response chorus. Less apologetic than “Everything,” the lyrics resolutely leave yesterday behind; “God willing I will love this day, I’ve been giving my past away /Now I’m living with the best of me and a picture of what used to be.” An extended instrumental coda ebbs and flows with liquid arpeggios, celestial strings and drifting bass lines; a graceful finish to a truly perfect record.

For 40 years, Chris Difford and Glenn Tilbrook have been the mainstays of Squeeze. With Jools Holland and Gilson Lavis sitting this album out, the duo relied mostly on bassists John Bentley and Lucy Shaw, drummer Simon Hanson and Stephen Large handled keys to flesh out their sound.

Cradle To Grave is quintessential Squeeze, their most accomplished effort since East Side Story. Of course, there can never be another Lennon & McCartney, but Difford and Tilbrook come close.