By Heidi Simmons

—–

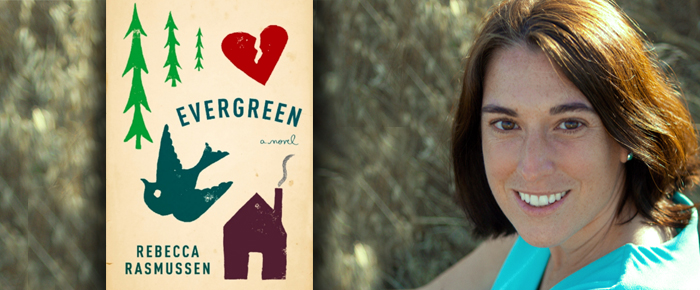

Evergreen

by Rebecca Rasmussen

Fiction

—–

There is a very romantic notion about making a home and building a life in the American wilderness. With hard work and perseverance, many of our ancestors successfully carved out an existence and made communities. Whether in a desert or a forest, they raised families under the most challenging circumstances. In Rebecca Rasmussen’s, Evergreen (Knopf, 352 pages) settling and taming the wild is not only about a place.

The story begins in 1938 after the young city girl Eveline is swept off her feet by Emil, a German immigrant, when he gives her a preserved butterfly. Having been raised on the edge of the Black Forest, Emil decides to settle in the thick woods of rural Minnesota. Now, married and pregnant, the couple must make a home out of an abandoned cabin, prepare for a baby and the harsh winter.

Eveline does her very best to not complain about their new lives, although it is difficult and extremely lonely. Soon their son, Hux, is born and the love, dedication and hard work of Emil gives her confidence that their future will be okay. Then Emil is called back to Germany to care for his dying father. Instead of going home to her parents, Eveline decides to stay and plant a garden, learn to fish and raise Hux in their cabin home.

Quickly out of her depth, Eveline is befriended by outcast and only forest neighbor Lulu and her young son Gunther. They become fast friends. Lulu is an extraordinary outdoorswoman and teaches Eveline how to survive. But just as Eveline thinks she can trust herself and the forest, she is betrayed and raped. She makes the hard choice to give up the baby girl to an orphanage.

Fourteen years later, Naamah, the abandoned child, raised by a brutal nun, leaves the orphanage abused and broken. More years pass and Hux is told about the child and the circumstances of her birth on Eveline’s deathbed.

With both his parents gone, Hux sets out to find his half-sister. When he does, he discovers she is a wild child prostitute who sleeps in the woods and scavenges food. Hux convinces her to come home to Evergreen, the place of her birth. After she tests Hux’s sincerity, she decides he’s family. In short order, Naamah meets Gunther.

Gunther and Naamah marry and have a child, Racine. It is another Evergreen generation and the wonderful coming together of two closely bonded families. But for Naamah, the pain and self-loathing renders her incapable of being a mom and she abandons her family and forest, leaving Gunther and Hux to raise Racine. The men do all they can to help Racine be happy and healthy in their beautiful forest community.

Author Rasmussen does not romanticize the wilderness lifestyle her characters face. The forest is difficult and lonely, but it is also majestic and comforting. The reader can smell the woods and feel the cool moist earth. The forest sounds at night are chilling and the morning sunlight warming. There is anticipation when Eveline triumphs and concern when she fails.

Evergreen is a story about good but broken people seeking a life connected to nature — a refuge from civilization and their tormented selves. For Eveline, Lulu, Naamah and Racine, it is a place where they are freer, less judged and have more gender equality. They are not born strong, but in order to survive the intense lifestyle, they become strong. Yet, as capable and independent as the women are, they are powerless to stop the violence against them.

Though this is a woman-centric novel, the featured men in the book are wonderful — all except one. They are hard working, supportive and respectful, capable of building partnerships with the women who keep their lives moving forward. Hux and Gunther are a new generation of exemplary males who treat woman better than mere equals.

Although the characters live outside civilization and without the basic modern conveniences of electricity and indoor plumbing, these forest dwellers manage a modern equitable existence devoid of artificially imposed gender roles.

Rasmussen manages to layer in significant themes over this multigenerational tale. Each family experiences abandonment. Lives are majorly altered because of the violence against women. Modern world conveniences may threaten their way of life more than aid it. There are certainly more haunting and meaningful subthemes lurking in the text.

There are times in Evergreen I wanted more interior voices from the characters and more details about everyday life in the wilderness. I would not have minded another hundred pages.

But the primitive setting is not what is most compelling about this colorful narrative. How does our environment shape who we are? Rasmussen starts the book with a quote from Ortega Y. Gasset: “Tell me the landscape in which you live, and I will tell you who you are.”

The bigger story may be the impact that our parents, grandparents and great-grandparents made as they carved a life out of this country by their hard work and perseverance — no matter what part of the nation they called home. We are all in the middle of our own wild multigenerational story.

Evergreen is available July 15.