By Eleni P. Austin

“Lately I’ve been thinking about our daughter growing old, all of the bullshit she might be told/There’s blood on the floor. maybe now you’ll believe her for sure?”

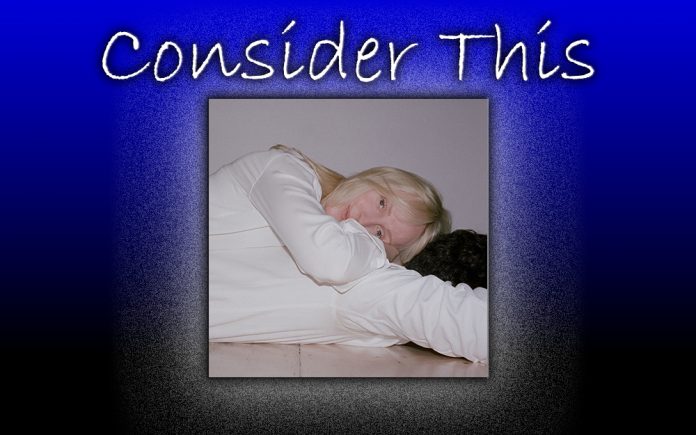

That’s Laura Marling looking forward on the title track from her latest album, “Song For Our Daughter.”

As music fans, it’s tempting to believe that every song a musician writes and sings, comes from deep personal experience. Sometimes that’s the case, sometimes the song comes from some astute observation. Sure, Bob Dylan probably knew someone who may (or may not) have been named Ramona, that he casually dumped in the early ‘60s, but do you really think he worked on Maggie’s Farm? Laura Marling hasn’t any children, and is, quite frankly, bored of people misinterpreting her music as first-person confessionals.

Born in 1990, the youngest of three daughters, she grew up surrounded by music. Her dad, Charlie, ran a recording studio on the family’s rural, Hampshire, England property. The La’s recorded their stunning debut album there, as did Heavy Metal pioneers, Black Sabbath. Laura took up guitar at an early age, by the time she was six, she’d mastered Neil Young’s terrifying treatise on drug addiction, “The Needle And The Damage Done.”

For her 13th birthday, she received two albums, Joni Mitchell’s Blue and Patty Smith’s Horses. Those two recordings changed her life. Three years later she relocated to London, intent on pursuing a career in music. Luckily, she fell in with a coterie of Folk-inspired musicians. By age 18, she had secured a record deal and released her debut, Alas I Cannot Swim. The effort was produced by former beau and Noah & The Whale front man, Charlie Fink. Critical acclaim was immediate and nearly unanimous, the British music press favorably compared her to Folk-Rock doyenne Joni Mitchell.

She quickly followed up with 2009’s I Speak Because I Can and 2011’s Creature I Don’t Know. The latter was produced by Ethan Johns, son of legendary producer Glyn Johns. Celebrated in his own right, Ethan had been behind or the boards for game-changing albums from Ryan Adams, the Jayhawks, Kings Of Leon and Rufus Wainwright (to name a select few). Their bond was immediate, and a creative partnership was born. Once again, the critics were effusive, and her popularity in the U.S. was gaining traction.

2013 saw the release of her watershed effort, Once I Was An Eagle. The record was a revelation. The melodies, instrumentation and arrangements seemed to draft off disparate influences like Joni Mitchell, Led Zeppelin, Kate Bush and Fairport Convention. The lyrics delved into the anguish of heartbreak, the restorative power of solitude and the romantic frisson of new love.

By this time, Laura had relocated to Los Angeles. For her fifth outing, she took a sharp left turn. Rather than rely on Ethan Johns, she handled production herself. Short Movie, released in 2015, spotlighted a surprisingly sanguine singing style and melodies and instrumentation that leaned closer to Electronica. Her notices were good, and the album sold well enough. But she had alienated her core audience.

She won them all back with Semper Femina, A stellar song cycle that charted the fickle nature of women. Ethan Johns was back on board for the 2017 release, Laura also enlisted singer-songwriter/producer Blake Mills. An enigmatic portrait shaded by nuance and heartbreak, it was a welcome return to form.

In the last couple of years, Laura has returned to her native England, setting up house with her sister and her boyfriend in London. She has also begun studying Psychoanalysis. Despite the flurry of activity, she found time to write and record her seventh long-player, Song For Our Daughter.

The opening two tracks offer a yin yang approach, creating a heady juxtaposition. “Alexandra” is spare and bare bones, opening tentatively, as strummy, sunshiny acoustic guitars fold into sturdy bass lines, searing pedal steel and an acrobatic rhythm. The lyrics draw inspiration from Leonard Cohen’s gloomy gem, “Alexandra’s Leaving.” Addressing the late troubadour directly she asks, “What became of Alexandra, did she make it through, what kind of woman gets to love you?” As the minor-key melody progresses, harmonies stack on the bridge as Laura’s mien turns more combative; “You had to say your shit to bed, you could not bear the unsaid, I had to try a fuck to give, why should I die, so you can live?” Wily pedal steel wraps around each verse cocooning the song in rich country comfort.

“Held Down” is more expansive, ambient loops shimmer around jangly acoustic guitar, spatial electric riffs, moony piano and an authoritative percussive kick. As sleek as “Alexandra” is stripped-down. Dreamy harmonies wash over siren-y guitars. Post-coital bliss becomes emotional interruptus, but Laura remains blasé; “I think about now with my legs wrapped around you, how many times before have you seen me run/It’s a cruel kind of twist that you’d leave like this, just drop my wrist and say ‘well, that’s us done’.” Following the taut, instrumental break, she delivers the verbal death blow; “You sent me your book which I gave half a look, but I just don’t care for and I cannot get through/But you’re writing again and I’m glad old friend, now make sure you write me out of where you get to.”

Inspiration is drawn from unexpected sources here. Take “Only The Strong,” the title is derived from a line in Robert Icke’s recent adaptation of the play, “Mary Stuart.” Downcast piano and lowing cello are buttressed by a kick-drum beat, quiescent acoustic guitars give way to more piquant riff-age. The lyrics offer a brittle post-mortem on a broken relationship with a mixture of insolence and regret; “Wish I could go back and find letters I wrote you in my mind/Perhaps I could unknot us from this awful bind, most I have forgot, or over refined.” Although her words are tinged with disdain, there is a catch and an ache to her vocals that barely conceal the hurt. The final verse strikes a more conciliatory tone; “Hoped that you can change my mind, I had to leave this crying all behind/I hope that you don’t think that I’m unkind, somebody told me that only and only, only the strong can survive.”

“Fortune” finds Ms. Marling musing on the sad fact that women are often times powerless to escape their fate. The winsome melody, fueled by willowy acoustic guitars and pastoral strings belie bittersweet lyrics like “At least we agree that we’ve wasted our time, we’ll give up that we’ll meet down the line, better off measured in coffee and wine/I think on it fondly-now the truth can be told, some love is ancient and it lives in your soul, a fortune that never grows old.” Equal parts vulnerable and resolute, happiness remains elusive; “And so ends a story, I had hoped to change, I had to release us from unbearable pain, and I promise we won’t come here again.”

Part Torch song, part Folky lament, “The End Of The Affair” takes it’s title from the Graham Greene novel as well as the 1955 Edward Dmytryk film. Ambient synths bloop and blip under plangent acoustic guitars. Cryptic lyrics allude to a past adultery and a subsequent bargain with God; “Threw my head unto his chest, ‘I think we did our best. But now we must make good on words to God,’ answered with a weary breath, no need to say the rest- I fear that we’ve been lost to long.” Beatific harmonies shade the chorus, but her last words; “I love you, goodbye— now let me live my life,” are suffused with longing and remorse.

On an album stacked with superlative songs, three stand out from the pack, the title track, “Strange Girl” and “Hope We Meet Again.” On the aforementioned “Song For Our Daughter,” Laura’s melismatic croon crests over filigreed acoustic fretwork, chunky piano notes and a swoony string section. Even as her voice is tender and intime, a vivid mise-en-scene unspools, tilting the balance of power in a #metoo direction; “Though they may want you to tread in their trail, only to see if the path they set fails, though they may want you to take off your clothes, whatever they think that the action exposed/With your clothes on the floor, taking advice from some old balding bore, you’ll ask yourself ‘did I want this at all?’” Feathery strings echo and sway on the break and a thumping beat kicks in. Although the pronouns are all second person, there’s a measure of authenticity that inclines it toward the first.

Breezy and bumptious, “Strange Girl” is a slinky Samba that positively shimmers. Anchored by angular bass lines, an agile backbeat and lissome guitars it shares some musical DNA with Joni Mitchell’s “Big Yellow Taxi.” Sharp, sardonic lyrics take an impetuous dilettante (or perhaps herself) to task; “Build yourself a garden and have something to attend, cut off all relations because you could not stand your friends/Announce yourself a socialist to have something to defend, oh yawn, girl please, don’t bullshit me.” As the melody rounds the corner on the bridge, harmonies coalesce with the instrumentation and the result (to unintentionally quote Robert Palmer), is simply irresistible.

Meanwhile, “Hope We Meet…” feels confessional and conversational, conjuring up the ghosts of Sandy Denny and Nick Drake. Finger-picked acoustic notes ebb and flow, atop sylvan strings and high lonesome pedal steel. Within the first verse, she’s swiftly rebuked a wayward swain; “I’ve lived my life in fits and spurts-maybe I’ve had more than I deserve, I’m sure I cannot feel much worse (I kept your letter, I read your words)/I tried to give you love and truth, but you’re acid-tongued, serpent toothed, I tried to share the map with you, but you knew your way, you had your route.” Still, at the end, she magnanimously manages a soupcon of empathy, noting “I hope we meet again, hope you never change.”

Ironically, a life-long Lennon acolyte, Laura has just recently begun to appreciate the melodic genius of Paul McCartney, and has characterized a couple tracks, “Blow By Blow” and “For You” as homages to the former Mop-Top. The former is a piano-driven ballad accented by wistful keys, as lush cello notes color the margins of the desolate melody. An emotional inventory is taken and it leads to this sharp epiphany; “Note by note, bruise by bruise, sometimes the hardest thing to learn is what you get from what you lose.”

The latter, which closes the record, is an aural pentimento played in ¾ time. Over Countrified guitars and Celtic keys (that kinda-sorta echo Macca’s “Mull Of Kintyre”), it contains this lovely and knowing couplet “Now that I have you, I will not forget what a miracle you are, no childish expectation, love is not the answer, but the line that marks the start.” It’s a sweet and playful end to a terrific record.

Along with Laura on vocals, acoustic, electric, slide guitars and guiro, the album features Dan See on drums, Nick Pini on bass and bowed double bass, Anna Corcoran on piano Dom Monks on Loops and Gabriel Cabezas on cello. Ethan Johns pitched in on drums, continuum, Resonator guitar, shaker and Moog. Legendary Byrds/Flying Burrito Brother Chris Hillman added pedal steel guitar.

Song For Our Daughter finds Laura Marling on the cusp of her ‘30s, casting her gaze toward the future while keeping an eye in the rearview. But no matter her intention, once again she has managed reach in and put a string of lights around our hearts.