By Dee Jae Cox

Theatre has always been a reflection of cultural attitudes and a mirror to reflect the diversity of American society. It is therefore critical to recognize and appreciate the varied histories of American theatre, rather than believing it to be one history, written primarily by white men for white America. Since 1976, every U.S. president has officially designated the month of February as Black History Month.

In celebrating the accomplishments and incredible history of American Theatre, there is no denying the invaluable contributions of African American artists. Though rich in history, tradition, mythology, music, song and dance, following the Civil War, the work of black performance artists was originally reduced to the traveling minstrel shows of the 19th century, (then called “Ethiopian minstrelsy.”) These shows were written by white male minstrels (Traveling musicians,) and based strongly on racial stereotypes.

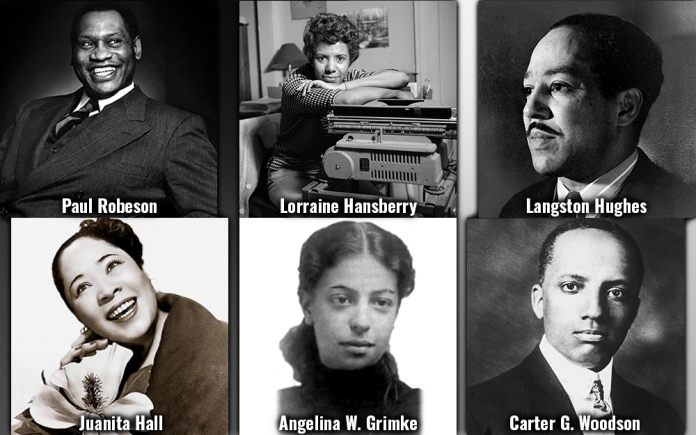

But by the turn of the 20th century most of the producing writing, and acting was being done entirely by black Americans. The first noted success of a black dramatist was Angelina Weld Grimke’s, ‘Rachel.’ Grimke, was the daughter of prominent bi-racial family of abolitionists and civil-rights activists. ‘Rachel,’ was produced in 1916 and published in 1920 and is about a young woman who is so horrified by racism, that she vows never to bring children into the world. (A radical notion at the time.)

Black theatre seriously began to take root during the Harlem Renaissance, (1920’s and 30’s) when African American culture, particularly in the creative arts, flourished and is remembered as one of the most influential movements in African American literary history. Literature, music, theatre and visual arts, began to reshape and present black Americans from their own experiences and perspectives outside of the white stereotypes that had influenced black peoples’ relationship to their heritage and to each other.

As the twentieth century progressed, experimental groups and black theatre companies emerged in Chicago, New York City and Washington, D.C. It was during this time that the Ethiopian Art Theatre, established Paul Robeson, as America’s foremost black actor. Robeson, was the son of a former slave. He obtained a law degree at Columbia University, but due to blatant racism and lack of opportunity in the field of law, he moved into an acting career with great success.

Garland Anderson’s play ‘Appearances’ (1925) was the first play of black authorship to be produced on Broadway, but black theatre did not create a Broadway hit until Langston Hughes’s, Mulatto won great success in 1935. Hughes, was one of the most important writers during the first half of the twentieth century. His work gave voice to the black experience, something sorely lacking in American literature and culture.

The Federal Theatre Project, was also founded in 1935, providing a training ground for black actors. In the late 1930s, black community theatres began to appear, revealing talents such as those of Ossie Davis and Ruby Dee. By 1940 black theatre was becoming more established and organized in America.

After WWII black theatre artists grew more progressive in their efforts to establish an identity outside of the predominant white theatre culture. Councils were organized to abolish the use of racial stereotypes in theatre and to integrate black playwrights into the mainstream of American theatre.

In 1950, actress Juanita Hall, became the first African American to win a Tony Award, (Best Supporting Actress,) for her role as Bloody Mary, in the stage version of Rodger’s and Hammerstein’s, South Pacific.

Lorraine Hansberry’s drama, ‘A Raisin in the Sun,’ staged in 1959, was the first show written by a black woman to ever be produced on Broadway. Hansberry’s title was taken from Langston Hughes poem;

‘Harlem,’

What happens to a dream deferred?

Does it dry up

like a raisin in the sun?

At the age of 29, Hansberry, won the New York Drama Critics’ Circle Award, making her the first African American dramatist, the fifth woman, and the youngest playwright to do so. The Sign in Sidney Brustein’s Window was the second and last staged play by Hansberry. The play opened on Broadway on October 15, 1964 and played its final performance Sunday, January 10, 1965, two days before Hansberry passed away at the young age of 34 from cancer.

Hansberry’s, ‘A Raisin in the Sun,’ and other successful black plays of the 1950s and 60’s, portrayed the difficulty of African Americans maintaining an identity in a society that degraded them.

The 1960s saw the emergence of a new black theatre, more defiant than its predecessors, with a goal of breaking racial barriers and stereotypes. Playwright Amiri Baraka (birth name LeRoi Jones) was one of the strongest proponents of depicted whites’ exploitation of blacks. He established the Black Arts Repertory Theatre in Harlem in 1965 and inspired other playwrights to create a strong “black aesthetic” in American theatre.

In the contemporary era of modern theatre, playwrights such as August Wilson, Suzan-Lori Parks, Lynn Nottage, all Pulitzer Prize winning playwrights, (Parks, was the first African American woman to win the prize, Nottage, was the first African American woman to win it twice,) have become strong symbols of achievement in American theatre.

Black theatre has grown immeasurably. African Americans have created dramas, comedies, musicals and every conceivable form of creative expression. Their contributions in the performing arts is vital to the growth, history and evolution of American theatre. Though statistics still reveal that a radical racial (and gender) disparity exists on American stages.

In a study of demographics for the 2016/17 season for on and Off-Broadway theatres, the report found that 86.8 percent of all shows produced were by white playwrights and 87.1 percent of all directors hired were white. Though the gender disparity was extreme. 75.4 percent of all plays written were by men, and 68.2 percent of all directors were men. (This lines-up with similar numbers released by the League of Professional Women.) Demographically, among actors, African American performers received only 18.6 percent of roles.

“All which I feel I must write has become obsessive. So many truths seem to be rushing at me as the result of things felt and seen and lived through. Oh, what I think I must tell this world.”—Lorraine Hansberry

Dee Jae Cox is a playwright, director and producer. She is the Cofounder and Artistic Director for The Los Angeles Women’s Theatre Project www.losangeleswomenstheatreproject.org www.palmspringstheatre.com