By Heidi Simmons

—–

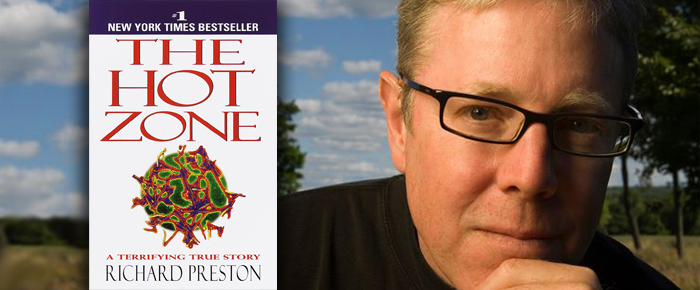

The Hot Zone

By Richard Preston

Non-Fiction

—–

Ebola, the deadly virus from Africa is here. It has made its way to the United State and has spread. So far, there have been eight cases and only one death. The government and health organizations apparently caught off guard, have since revised protocols to try to catch it early, stop potential outbreaks and control contamination. In Richard Preston’s 1994 bestseller, The Hot Zone (Random House, 300 pages), the reader gets up-close and personal with Ebola without the risk of infection.

Preston’s book is a thriller. If blood and bodily fluids make you queasy this horror story is not for you. This is a non-fiction nightmare.

The Hot Zone begins with Charles Monet, a middle aged French expatriate living in Kenya. On New Year’s weekend in 1980, he and a girl friend went to Mount Elgon, an ancient volcano on the border of Uganda and Kenya, not far from Sudan. The rural area is rich with rain forests, great African beasts and small villages of Masai. Monet explored a cave called Kitum. Although the cave opening was hard to find, its interior was the size of a football field. The cave had petrified wood and bones, glittering crystals and giant insects.

Seven days later he had a headache that would not go away. Three days after that he became nauseated. He had a fever and his vomiting grew into dry heaves. His eyelids were droopy and his face lost all expression. His eyes bulged from their sockets and were bright red. His face yellowed with red star-like speckles. Monet was sullen, angry and confused. His personality was gone.

Friends took Monet to the hospital, where he received antibiotics. It did not work. Doctors recommended he go to Nairobi Hospital, the best in East Africa. Monet got on a plane without help and managed to get to the hospital. There in the lobby, he bled out—spontaneous liquefaction. From every orifice, black gooey blood and guts spewed over the floor. The virus had eaten away his mind and body and was now seeking a new living host!

An emergency room doctor tried to clear his airway with his hand. Monet still had a slight pulse and stared into the doctor’s eyes. Monet heaved and coughed into the doctor’s face. Monet was breathing. The doctor tried to give Monet fluids and a blood transfusion, but every time he put a needle in a vein, it would fail. The vain would collapse and the blood would not clot. Monet went into a coma and never regained consciousness. Monet died with the doctor at his side.

Nine days later, Monet’s doctor, Shem Musoke, had the virus. Musoke’s doctors collected blood samples and serum and sent frozen tubes to labs around the globe to identify the cause.

It was a form of Marburg: an African organism named for a city in central Germany. A factory there in 1967 was producing vaccines using cells from imported Ugandan monkeys. The monkeys were ill. Called “virus amplification,” the virus soon jumped species, from monkey to human. Thirty-one people caught the virus and seven died just like Monet.

Marburg is a filovirus –Latin meaning “thread virus.” In a microscope, it looks like, tangled rope, worms or snakes. When the samples of the virus reached the United States, Musoke’s virus was identified as Ebola. The name and virus came from the area around the Ebola River in Zaire. It was considered one of three sisters: Marburg, Ebola Sudan and Ebola Zaire. All lethal. Fortunately, doctor Musoke survived.

In 1990, a new Ebola reared its ugly head at the Reston Primate Quarantine Unit in Virginia. The monkeys were dying with Ebola symptoms. It was not clear how it was spreading in the monkey house since they were held in different rooms only connected by a ventilation system. And these monkeys were natives of the Philippines, not Africa.

The United States Army Medical Research Institute of Infectious Diseases at Fort Detrick took control of the situation. After some politics and debate, the Center for Disease Control joined the efforts. Five workers were exposed, three got sick, but not with Ebola. Four hundred and fifty animals were euthanized and autopsied.

The scientists involved concluded the virus must have spread through the air at the facility. This strain was named Ebola Reston. It was treated as a “level 4 hot agent” – a virus that is extremely lethal and potentially airborne for which there are no vaccines and no cure. Ebola Reston had the same spaghetti-like structure and the monkeys died just like Monet. But, it appeared it may not be dangerous to humans. Is Ebola Reston a mutation?

Ebola is a serious and mysterious virus. It is neither dead not alive. It cannot live on its own, but once it finds a cell to penetrate, it goes wild. The virus tries to convert the host into itself!

Ebola has seven proteins. At the time The Hot Zone was written, only four were unidentified. It’s thought that the virus has been on the planet a million years. Earlier outbreaks might have been contained because humans naturally quarantined themselves, thus keeping the virus in the village until it burned out.

The author writes about Ebola with incredible suspense. The details are terrifying. Preston says: “A hot virus from the rain forest lives within a twenty-four hour plane flight from every city on earth.” If airborne, it could circle the globe in about six hours!

The Ebola outbreak continues to concern governments, the CDC, the World Health Organization, healthcare workers and the human population. Supposedly, there is a treatment for Ebola. Certainly, some things have changed since The Hot Zone was published twenty years ago, but the danger of Ebola and its curious nature remain a mystery and a threat.