By Eleni P. Austin

“Special thanks from these louses to our spouses for letting us make all this racket around the houses”

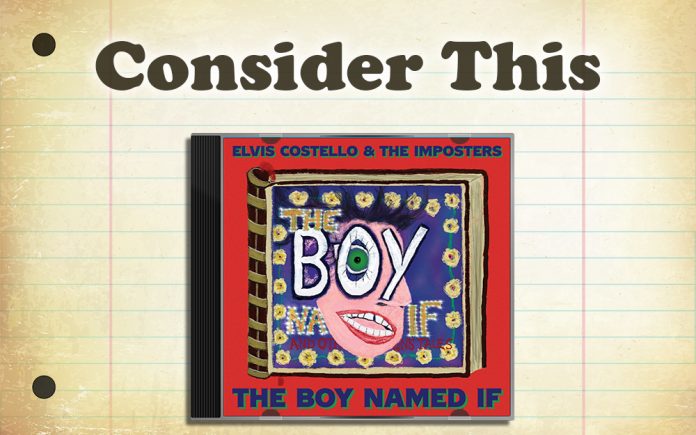

That pithy tribute is found at the bottom of the liner notes for Elvis Costello’s combustible new album, The Boy Named If.

Elvis Costello burst on the British music scene 45 years ago. Part of the inaugural Punk Class of ’77, his classmates included The Clash, The Jam, The Damned and the Sex Pistols. Some of those bands would evolve, some would quickly implode.

Born Declan McManus, he was the only child of Ross and Lillian, growing up in London and Birkenhead, he was surrounded by music. His dad was the vocalist for the Joe Loss Orchestra and his mother worked in a record shop. His earliest musical crushes were Frank Sinatra and Ella Fitzgerald.

At age nine, young Declan knew he would be a writer. Coincidently, that same year, The Beatles blew his mind. By his teens he had expanded his sphere of influences, becoming enamored by everyone from the Beach Boys and The Band, to the Grateful Dead, Randy Newman, Tamla/Motown and N.R.B.Q. He’d picked up the guitar by then and began writing his own songs. He started performing as part of a duo, then moved on to fronting the band Flip City, before venturing out on his own.

Armed with only his acoustic guitar and an arsenal of killer songs, he won over the folks at Stiff Records and acquired the management services of Jake Riviera (who talked him into adopting the stage name Elvis Costello). Busking at a record company convention, he managed to secure a deal at Columbia Records.

Musically speaking, his sound was much more sophisticated than his peers, Elvis quickly realized that Punk Rock allowed him to get by with only a handful of guitar chords and stripped-down instrumentation, putting his lyrics front and center. His debut, My Aim Is True, was realized with the assistance of Clover, a backing band from sunny California. Released in 1977, the record was immediately embraced by fans and critics alike. His lyrical acumen was bookended by concise melodies, no-nonsense arrangements, and brisk instrumentation.

Heading out on his first real tour, he recruited bassist Bruce Thomas, drummer Pete Thomas (no relation) and Steve Nieve on keys. Together, they became Elvis Costello And The Attractions. During their tenure at Columbia, the four-piece effortlessly hopscotched through myriad styles, starting with the take-no-prisoners snarl of This Year’s Model, and the New Wave/Power Pop of Armed Forces. His fourth record, Get Happy was a spiky homage to Motown and Stax Soul/R&B. Meanwhile, Almost Blue found him covering songs by Honky-Tonk heroes like Hank Williams, Sr. and Merle Haggard, Imperial Bedroom was a bespoke, Baroque masterpiece and King Of America was an affectionate nod to Roots Rock.

Although he parted ways with the Attractions in 1986, they reunited eight years later for two more stellar albums. In between and after, Elvis continued to follow his muse, producing albums by The Specials, Squeeze and The Pogues. He wrote music with (childhood idol) Paul McCartney, created a Classical song suite to perform with The Brodsky Quartet, whipped up an album from scratch with legendary songwriter Burt Bacharach. 20 years ago, he reconvened The Attractions sans Bruce, with the addition of Davey Faragher (John Hiatt, Cracker) on bass, and The Imposters were born. In the ensuing years he has collaborated with everyone from Allen Toussaint to Jim Lauderdale to The Roots. 2015 saw the release of his thoughtful and thought-provoking autobiography, Unfaithful Music And Disappearing Ink. Three years later he and the Imposters released a worthy successor to Imperial Bedroom entitled Look Now. A pandemic defying solo effort, Hey Clockface followed in late 2020.

As Covid ebbed and flowed, Elvis and longtime producer Sebastian Krys dusted off the Attractions’ backing tracks and stripped away EC’s lead vocals from the This Year’s Model album. Enlisting Latin music superstars like Juanes, Luis Fonsi and Jorge Drexler, among many others, to add their own vocals, strictly en espanol. The result, Spanish Model, became his first Top 10 album on the Latin Pop charts. Recently he reunited with the Imposters and recording remotely, has just released his 32nd long-player, The Boy Named If.

The opening cut hurtles out of the speakers with the primitive cool of “Farewell, Ok.” A kissing cousin to Chuck Berry’s epochal “School Days,” the melody and arrangement, all rapid-fire guitars, pounding piano, wheezy Continental Vox organ, throbbing bass lines and punishing beat, also shares some musical DNA with touchstones like Little Richard’s “Bama Lama, Bama Lou” and “I Saw Her Standing There,” by the Fab Four. The vitriolic lyrics, however, are pure Costello. It’s a bitter kiss-off, he coolly eviscerates faithless lover, kicking her to the curb with his usual mix of erudition and verbal venom; “Goodbye, so long, there’s no right or wrong, this might be the final word I chance in the very last dance, the appeal of the trumpet to a pearl of red laughter/Of lipstick and kisses right here under the rafter, a fumble for heaven in a thimble of draft, and a seldom of Elvis in the velvet hereafter, farewell ok, farewell ok, farewell ok.” That’s Elvis-speak for get out.

The next three songs unspool with the sort of feral ferocity that characterized Elvis’ earliest albums. On the title track shuddery acoustic guitars line up next to menacing keys, wiggly bass lines and a truncheon beat. Lyrics resurrect an imaginary doppelganger from childhood, the devil on his shoulder who encourages bad behavior by promising no consequences; “I’m a lucky so and so, a fortunate stiff, you said you never knew me but I’m the one you want to be with, if I tumble from a tightrope or leap from a cliff, I won’t be dashed to pieces, I’m the boy named ‘IF.’ As the arrangement slowly accelerates, like a roller coaster clanking up to the summit, the tension rachets, darting organ notes slither around Sci-Fi keys as Elvis unleashes a scabrous guitar solo thick with wicked intention.

“Penelope Halfpenny” clatters to life with a fusillade of drums, vroom-y bass, carnival keys and jittery guitars. Elvis’ snarly vocal delivery belies lyrics loosely based on a teacher he sorta crushed on as a kid. Realizing even then, that teaching wasn’t her true vocation, he imagines she is destined for grander things; “Penelope Halfpenny asked a great deal, turned on her heel through her squandered ambitions while marking her time, taught lessons to all adjacent to crime from her days reporting to the Scotland Yard blotter/Who got who and who who got what, but none of that mattered, not one jot, to Penelope, Penelope, Penelope, Penelope Halfpenny.” Swirly keys and plonky piano leap ahead of grumbling guitars and rumbling drums on the break, as Penelope “disappeared with the dot of a decimal place,” a rough and tumble chiming guitar coda seems to seal her fate.

On “The Difference,” strummy acoustic guitars partner with wily bass runs and a clickity-clack beat before locking into a relax-fit Cha-Cha-Cha. Angular electric riffs and pealing piano notes ping-pong through the arrangement. Meanwhile, Elvis’ quavery vocals wrap around dense lyrics that are equal parts adulterous and Oedipal; “My father shamed me just like you, buried my name in a glass or two, ‘til he came to me in his darkest house, he mistook me, took me for his spouse, and my cries for a woman in the distance, so I took this knife to show him the difference.”

In recent interviews, Elvis has stated the songs on this record turns the spotlight on that tumultuous transition between adolescence and adulthood, (inspired somewhat by his and his wife, Jazz chanteuse Diana Krall’s twin boys who have recently entered their teens). But he also manages to work in his usual themes of guilt, infidelity and shame. Take “Mistook Me For A Friend,” which blends a pounding backbeat, sugary keys, shivery guitars and throbbing bass. Elvis’ no-nonsense mien is matched by a pragmatic arrangement. All manner of grift, graft and chicanery are folded in to a nuanced narrative worthy of Raymond Chandler; “I had a pocketful of Presidents, a suitcase full of elements, the double-cross of spectacles, a mogul for the mechanicals…You took your clothes off after you sent him away, why now baby, would you ask me to stay, I knew it wasn’t right, if I could just pretend mistook you for a friend.”

Then there’s “What If I Can’t Give You Anything But Love.” Revved-up drums, souped-up bass, sputtery electric piano and guttural guitars coil around the melody in hiccough-y waltz time. Hoping for some romantic reciprocity, he wears his heart on his sleeve; “Do you love me? It’s dangerous to answer in the dark, do you need me? Hold on while I negotiate the spark, anticipate an impulse, tell me what I’m supposed to do, do you want me? Do you want me? Like I want you” Dissatisfied with the reply he rips a skronky guitar solo and then casually reveals “when this is over, I’ll go back to my wife, I’m the man she lives with, in that other life.”

This record is wall-to-wall brilliant, but two tracks stand out, “Magnificent Hurt” and “The Death Of Magical Thinking.” The former, which is also the album’s first single and it simply struts. Boinging bass connects with prickly guitar, spacey, Evil Genius keys and a ricochet rhythm. The melody and arrangement land in that sweet spot between ‘60s Garage Rock and late ‘70s New Wave. Lyrics limn the exquisite pain (the French call it la douleur exquise), that accompanies the first stirrings of carnal desire; “When we first met, I knew you were beautiful, you fit like the seat of a mohair suit, but the pain that I felt let me know I’m alive and I opened up my heart to the way you make me feel, magnificent hurt.”

The latter opens with a Tsunami of drums, quickly matched by slashing guitars, flickering bass and snake charmer keys. Lyrics capture that perfect storm of angst and sangfroid, when teenage lust blurs all thoughts of algebra; “She took my hand in an experiment, put it where it shouldn’t be, put it underneath her dress and waited to see, I didn’t know what to do, I didn’t know what to say, it was just a game I guess, one I didn’t know how to play.” On the break, cyclonic guitars ebb and flow as drums pummel and quake. Much like “Lipstick Vogue” from 1978, this track shines the spotlight on Pete’s prodigious percussive attack.

The action slows briefly on a couple of songs. On “My Most Beautiful Mistake, tremulous guitars, whooshy keys and spidery bass lines are wed to a rock steady beat. The opening couplet alone is worth the price of admission, as it’s replete with Elvis’ signature wordplay; “She was a part-time waitress with a dream of greatness, that nobody even suspected, though it was sometimes reflected in the slant of the mirror, it was buried so deep and so dear.” The deft reportage continues, checking in with a “one-hit wonder kid” before refocusing on our heroine; “From the booth in the corner from a different perspective, where the man plays a fool or a private detective/He wrote her name in sugar on the Formica counter, ‘you could be the game that captures the hunter’ then he went out for cigarettes as the soundtrack played The Marvelettes.”

“Paint The Red Rose Blue” is an aching ballad that blends swoony organ, monochromatic guitars, sturdy bass and a tick-tock beat. This serpentine saga navigates the vagaries of married life; “The words that came to him, both the lies and the threats, they arrived all to easily, but they ran up some debts/From the thunder of the pulpit to the whispers of a lover, ‘til he found out he couldn’t tell one from the other.” Elvis’ willowy croon is suffused in recrimination and regret.

Other interesting songs include “The Man You Love To Hate” and “Trick Out The Truth.” Both follow in the tradition of Costello classics like “God’s Comic” or “Jimmy Standing In The Rain” by fusing sharply sardonic lyrics to arch, Music Hall melodies. “The Man..” is a shaggy-dog story powered by skittery guitars, barbed bass, roller-rink keys and a thunky beat. Elvis affects a Snidely Whiplash vibe, practically twirling an imaginary moustache. “Trick…” employs stutter-step guitars, bloopy keys, sinewy bass and a see-saw rhythm. Here, Elvis’ vaudevillian vocal delivery is in full effect as he namechecks Marxists, Marx Brothers, Helen Of Troy, Myrna Loy, Mahler, Godiva and Godzilla.

The album closes with “Mr. Crescent,” a mid-tempo ballad that harkens back to older deep cuts like “All The Rage” and “Radio Silence.” There’s a reticence and arrogance, terror + magnificence in this opaque character study. It’s buoyed by jangly acoustic guitar, thrumming bass, trembling electric guitar, clipped keys and a kickdrum beat. A low-rate lothario, who has his way with women then beats a hasty retreat, he receives a stinging rebuke from an unlikely source; “Crescent is like a man I knew, left me standing there with nothing but you, don’t be fooled now by his bill and coo, you’ll be abandoned too, he’ll leave you with an I.O.U.” The song shudders to a halt, finishing the record with a note of intrigue.

At this stage in his career, Elvis has very little left to prove. His true, ride-or-die fans have followed every twist and turn of his musical adventures and will probably continue to do so, (even if he suddenly evinced an affinity Polkas and Trap music). Still, it’s quite wonderful to hear him flexing musical muscles he hasn’t relied on in years.

The Boy Named If stacks up nicely with classic Costello records like This Year’s Model, Brutal Youth and When I Was Cruel. It’s the ultimate exhale, reminding you of why you fell in love with Elvis all those years ago. Raw, visceral and immediate. Exactly as it should be.