By Eleni P. Austin

Marshall Crenshaw’s self-titled debut arrived 40 years ago. The dayglo cover art managed to walk the line between retro and au courant. The music contained therein was a fresh, yet familiar mash-up of Rock, Soul, R&B, Rockabilly and Country wrapped in iridescent New Wave colors. Embraced by cutting edge radio stations like KROQ in Los Angeles, songs like “Someday, Someway” and “Cynical Girl,” stood out next to Synth-Pop hits by Soft Cell, Human League and Depeche Mode. It felt as though Marshal burst on the scene out of nowhere. But he had been preparing for this moment since he picked up a guitar at age 10.

Born in 1953, The Michigan native grew up in Berkley, a suburb outside Detroit. He cycled through a series of bands in high school. His original inspiration were British Invasion bands like The Beatles, The Stones, the Kinks and The Who. But by his early 20s, he was bored by Top 40 radio, and he began searching out old music that toggled between primitive ‘50s Rock & Roll and romantic R&B. These were the genres that informed his earliest attempts at songwriting.

Following a stint playing John Lennon in a touring company of the Broadway hit, Beatlemania, Marshall relocated to New York City. Armed with an arsenal of original songs, he enlisted his brother Robert to play drums and auditioned a plethora of bassists before Chris Donato completed his nascent three-piece combo. He tirelessly dropped demos with various showbiz movers and shakers and his perseverance paid off. Marshall connected with journalist and music producer Alan Bettrock, and eventually signed with Warner Brothers Records. His debut was produced by Richard Gotterher (Blondie, the Go-Go’s). Not only did the record, an irresistible fusion of Rock, Country, Rockabilly, Power-Pop and Soul garner ecstatic reviews, it also scored a Top 40 hit.

Throughout the ‘80s, Marshall released a string of excellent albums, Field Day, Downtown, Mary Jean & 9 Others and Good Evening, respectively. Although they never hit the commercial heights of the debut, each record achieved critical acclaim, pleasing his growing legion of fans.

That measure of excellence continued during the next decade and well into the 21st century with long-players like Life’s Too Short, Miracle of Science, Jaggedland and #392, as well as a few live efforts, Live…… My Truck Is My Home, I’ve Suffered For My Art…Now It’s Your Turn and The Wild Exciting Sounds Of Marshall Crenshaw: Live In The 20th and 21st Century.

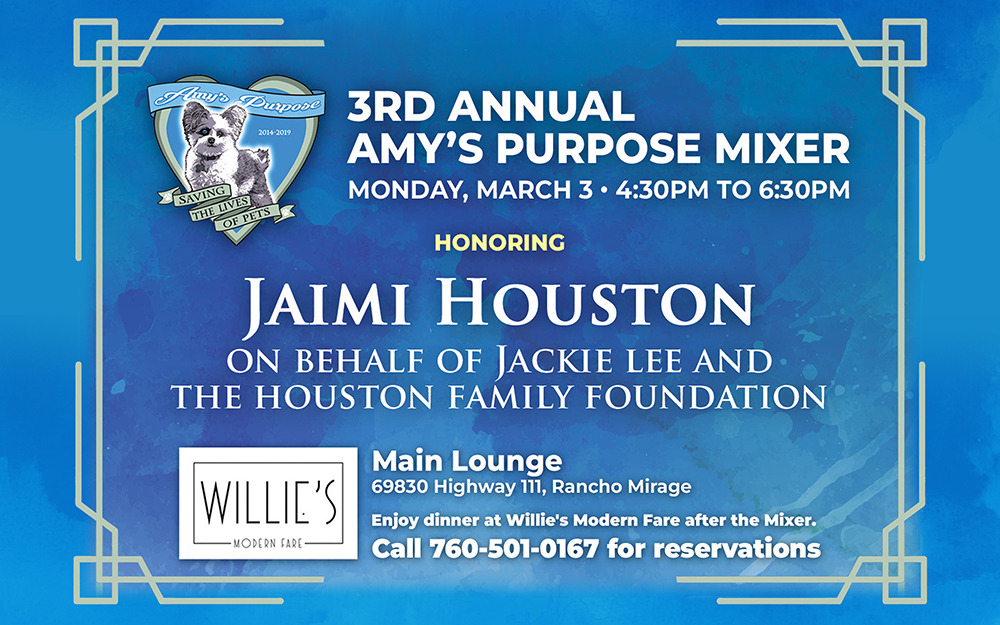

Recently, Marshall regained ownership of the five celebrated records he released via the Razor & Tie label between 1994 and 2003. Rather ambitiously, he has begun reissuing each album in expanded CD, vinyl and digital configurations. 1996’s Miracle Of Science arrived in early 2020, now he’s returned with a minty-fresh edition of 1999’s #447.

The record crackles to life with a bit of jump, jive and wail entitled “Opening (It’s All About Rock).” The finger-poppin,’ honking sax salvo is ruthlessly interrupted with a flip of the radio dial, landing on track number two, “Dime A Dozen Guy.” Lithe guitar riffs connect with prowling bass lines and a kinetic beat. A Noirish narrative places Marshall in the shadows, tailing an ex, who is out on the town with a garden-variety gigolo. Equal parts indignant and dumbfounded he can’t understand the attraction; “He’s not good-looking, at least I don’t think so, I just can’t figure any earthly reason why, a girl like her would choose a dime-a-dozen guy.” Twinkly keys and jangly guitars wrap around each verse as he realizes he’s been left in the dust. Finally, he concedes his culpability; “Guess I was thoughtless, careless too, I disappeared on her it’s true, now I realize I wasted something I cared about, that’s why I’m blue.” Not one, but two cathartic solos take flight, skittish and stinging, awash with bitterness and regret.

The vagaries of love seems to be the unspoken theme that threads through this record. Take the sumptuous “Truly, Madly, Deeply,” Marshall’s boyish tenor lattices atop sunny acoustic notes, billowy keys, nimble electric guitars, slinky bass and a syncopated rhythm. The dreamy and Everly-esque melody is matched by this uncomplicated declaration of love; “And how the hours fly by, cause life is all around us, so much to talk and laugh about between you and me/Oh it feels so fine to know you got something more than what you might dream of, and know right here and now, I know that I’m truly, madly, deeply in love.” A succinct guitar solo unspools on the break, equal parts pithy and acrobatic.

The candy-coated crunch of “Right In Front Of Me” is anchored by buzzy bass, fuzz-encrusted guitars and a hiccough-y back-beat. Lyrics limn the drifting-falling sensation of falling for a friend; “You got my heart there’s no doubt, I thought I was smart, now I’ve got to laugh about how much I didn’t know/Just a little while ago you were someone I could call friend, that I would turn to every now and then, that’s all I thought there was, when it came to the two of us.” Plinky piano low in the mix adds to the arrangement’s urgency as Marshall stacks his vocals high and low before unleashing a choogling solo that straddles the line between efficiency and exuberance.

“Glad Goodbye” is jagged and sinewy. Dobro and lap steel intersect with roughhewn guitars, stand-up bass and a slightly akimbo rhythm. Splitting the difference between mercurial and meticulous, equivocal lyrics sketch out a restless farewell; “And you know you’ve got to go, you gotta do it when you know that what you thought you always loved is one you’re better off being rid of/We’re going with the changing of the season, without much sadness, without much fear, what waits over the horizon is not like anything we’ll ever find here.” Searing lap steel dovetails with knotty dobro riffs on the break stalling the inevitable valediction.

This record is wall-to-wall wonderful, but three songs truly stand out. First up is the moodily elegant “Television Light.” Brawny electric riff-age is woven into a melodic tapestry of chiming acoustic guitars, cascading mandolin notes, swooping violin and a bongo-rific beat. The opening couplet establishes that desolate sensation of feeling alone in a crowd, while pining for an ex; “Television light, shining through a hundred bedroom windows, I was out last night walking around the streets that we know, tales behind every door/No two are quite the same, you and I know a few of our own, that’s for sure.” A wobbly violin solo navigates both the bitter and the sweet.

Conversely, “Ready Right Now” finds our hero willing to take the plunge, romantically, that is. The melody is powered by razor-sharp guitar riffs, rumbling bass, sinister keys and a steady tom-tom tattoo. Ironically, lyrics dispense with any mushy declarations of love, opting for some “just the facts, ma’am” reportage; “This is no rehearsal, this is the one, and I swear it won’t be something casually done, with all and all of my energy every bit of life that’s left in me, I’m going to give you all that I have all that time will allow, I’m ready right now, right now.” Cutting loose on the break, stutter-y guitars ricochet through the mix, matched by manic handclaps and some wily electric piano. Ultimately, Marshall concedes “I don’t know what the future might hold, but I’ll try to never falter or lose control.”

Finally, “Tell Me All About It” opens tentatively with some woozy keys before downshifting into a tensile groove. Chunky guitars are bookended by angular bass, liquid keys and a rock-steady beat. Barely a month after a break-up, Marshall meets up with an ex, in an attempt to unpack their emotional baggage. Second-guessing seems to be the lyrical leitmotif; “Tangled hands and feet, all the words you whispered sweet, it’s all coming back now incomplete, did you just fake it/Now I do believe it’s just like Adam learned with Eve, people can hide things up their sleeve, even when naked.” This lovelorn post-mortem is buoyed by song’s monster melodic hook, along with the sure-footed arrangement and sanguine vocals. A honeyed guitar solo unfurls on the break evincing the confidence the lyrics lack.

The record is dotted with instrumentals, the languid “West Of Bald Knob” and the Jazzy “Eydie’s Tune” are the aural equivalent of musical sorbet, a pallet-cleanser between the heavier main courses. The original album closed with another, the breezy Blues of “You Said What??” But this new iteration tacks on two brand new recordings, “Will Of The Wind” and “Santa Fe,” to close out the set.

The former finds Marshall in top form. A brooding and muscular rocker, the taut arrangement is blends shuddery, distorto guitars, see-saw bass lines and a chugging beat. Written at the start of the pandemic, the lyrics (co-written by ex-Angry Samoans frontman, Gregg Turner), capture the collective malaise most of us experienced during lockdown. The latter is a sparkling rendition of the title-track from Gregg’s 1992 solo debut. Mournful guitars, keening pedal steel and a loping beat lock into a high lonesome groove, ending the record on a pensive note.

Although Marshall played drums, drum machines, percussion, guitars, mellotron, electric bass and celeste, he was aided and abetted by a wolfpack of pickers and players. They include Paul Shapiro on tenor sax, Dave Hofstra on stand-up bass, Pat Buchanan on guitar and power steel, Brad Jones on stand-up bass, Chamberlin strings, electric piano and combo organ, Rachel Handman on violin, Valentina Evans on viola, Chris Carmichael on viola, violin and fiddle, Mike Neer on steel guitar and Footch Fischetti on fiddle. Heavy-hitters included Andy York who added stacks of acoustics and lead guitar, Bill Lloyd played mandolin and a ‘ass-kickin tele,’ Greg Liesz provided dobro and lap steel and David Sancious played electric piano.

Have you ever revisited a record you loved decades ago, and it feels completely dated, antiquated and obsolete? It’s enough to make you doubt yourself. Happily, that just doesn’t happen with Marshall Crenshaw’s older albums. His music remains ageless. To paraphrase the the one-hit-wonder from the Spiral Staircase, You’ll love #447 more today than yesterday, but not as much as tomorrow.