By Eleni P. Austin

Back in the late ‘80s and early ‘90s, the Country music Industry was experiencing some serious growing pains. Slick and spangle-y Rhinestone cowboys and cowgirls had basically ruled the airwaves since the late ‘70s, skillfully excising the Hillbilly component so crucial to the genre.

Progenitors like Johnny Cash, Merle Haggard and George Jones had been cast aside, outlaws like Willie and Waylon were also pushed to the margins. Sterile and safe hit-makers like Kenny Rogers, Barbara Mandrell and Alabama were all the rage, and their sound hewed more closely to MOR Pop than Jimmie Rodgers’ “Blue Yodel No. 8” or Mother Maybelle’s “Wildwood Flower.”

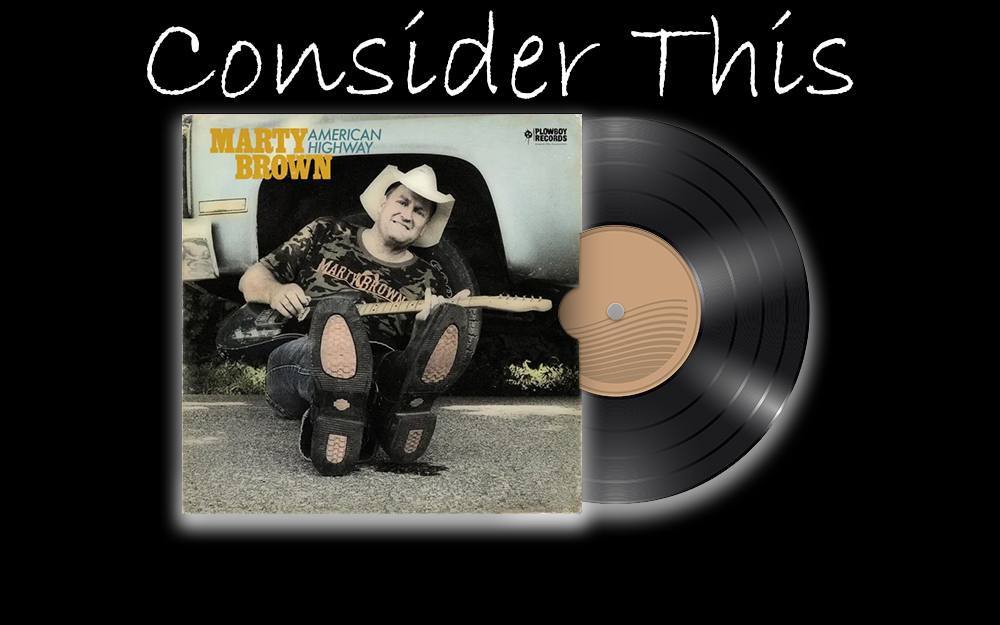

But things were looking up, outliers like k.d. lang, Lyle Lovett, Steve Earle and Nanci Griffith were making some in-roads. Neo-Traditionalists like Randy Travis, Marty Stuart and Dwight Yoakam were injecting some much-needed Honky-Tonk flavor. New artists like Garth Brooks, Clint Black and Kelly Willis took equal inspiration from Hank Williams Sr., James Taylor, Patsy Cline, the Eagles and ZZ Top. It was around this time that Marty Brown finally began making a name for himself in Nashville.

Born and raised in Maceo, Kentucky, Marty came of age at a time when Rock N’ Roll was just hitting its stride. But he grew up loving Country music. Sure, Elvis was an influence, but Johnny Cash, Merle Haggard, George Jones, Hank Sr. and the Everly Brothers provided true inspiration. He taught himself guitar at age nine, pretty soon he was holing up in the bathroom tape-recording his earliest attempts at songwriting. By the time he was in high school he’d written dozens of songs.

Marty married early, and divorced just as quickly after becoming a father of two. Still, he never abandoned dreams of musical stardom. Making ends meet as a plumber’s assistant and a mechanic, he began making forays into Nashville, hoping his songwriting skills would get his foot in the door. He once estimated he’d made about 100 trips there before he had any real success. He played some songs for an agent who promised to get him a recording contract. In a strange stroke of serendipity, the CBS series “48 Hours” filmed a segment focused on Country Music, hosted by Dan Rather that featured Marty. Suddenly, there was a bidding war between labels to secure Marty’s services.

Signed to MCA (home at the time to Steve Earle, Nanci Griffith and Lyle Lovett), his debut, High And Dry arrived in 1991. Critical acclaim was unanimous, radio airplay was practically non-existent. Ironically, his music was perhaps considered “too Country” for Country radio. Luckily, burgeoning music television networks like CMT (Country Music Television) and VH-1 (Video Hits 1, in case you forgot), picked up some of the slack.

Unfortunately, the label seemed to abdicate promotional responsibilities. Luckily, Marty persevered playing live wherever he could, that included state fairs and even Wal-Mart stores. He would actually pull up in a 1969 Cadillac Convertible, and play on a makeshift stage with just his guitar and an amp. He brought his music directly to the people, and his unconventional methods paid off. Entertainment Weekly and People magazine wrote glowing profiles about him and sales increased.

He followed up with two more stellar albums for MCA, 1993’s Wild Kentucky Skies and 1994’s Cryin,’ Lovin,’ Leavin’. Reviews were rapturous but sales were slim and his label dropped him. Marty inked a deal with respected indie label, HighTone. The Oakland label specialized in American Roots music as well as Blues, Gospel, Country, Rockabilly and Western Swing. It seemed like a perfect fit. 1996 saw the release of his fourth effort, Here’s To The Honky Tonks. Predictably, praise was high and sales were low. After that, Marty seemed to kind of disappear.

Behind the scenes he wrote hit songs for Trace Adkins, Brooks & Dunn and Tracy Byrd, but as a performer, he might as well have entered into musical Witness Protection. In the ensuing years he would occasionally pop up playing a live show in Kentucky, but the majority of his time was spent with his family, fishing, fixing cars and building bird boxes.

Flash forward to 2013, when his wife Shellie surprised him by taking him to Nashville to audition for the “America’s Got Talent” series. Not only did his rendition of Bob Dylan’s “To Make You Feel My Love” advance him to the semi-finals, it also generated over 11 million views on YouTube. The exposure raised his profile exponentially, independent labels took notice and Marty ended up signing with Plowboy Records. The label features an eclectic roster that includes seminal singer-songwriter Bobby Bare, Punk progenitors the Dead Boys and Television’s Richard Lloyd, Georgia alt. rockers Drivin N’ Cryin and Country pioneer Jim Ed Brown. It seemed like he found the right home. Now he has returned with his fifth official album, American Highway.

The record kicks into gear with the rollicking title track. Gritty guitar riffs connect with a tick-tock beat, rubbery bass lines and cascading piano notes. The lyrics offer a good ol’ boy paean to these United States. In lesser hands, lyrics like “I see church steeples, red white and blue barbershop poles, good-hearted hard-working people wherever I go on this American Highway,” would feel like a jingoistic Chevy commercial, veering into Lee Greenwood country. But the ever-present ache in Marty’s voice splits the difference between nostalgia and wishful thinking.

When his debut dropped in the early ‘90s, Marty’s music was favorably compared to Hank Williams Sr. and Jimmie Rodgers, there was a high lonesome quality that echoed those antecedents. On his new songs, he leans closer to the Rock N’ Roll sound he eschewed in his teens. Ah, irony.

Take “I’m On A Roll” which offers a master class in ‘70s Southern Boogie. Thrashy metallic guitar chords hug the hairpin turns of a chunky backbeat, chugging percussion and roiling bass. Ostensibly, the lyrics celebrate a streak of good fortune; “I got a roof that don’t leak and a well that never runs dry, I’ve got a good woman who’s happy just getting by/She’s an eleven on a scale of ten, who says losers can’t win, I’m on a roll and it’s better than it’s ever been.” But scratch beneath the surface and it seems clear that it took at least 12 steps to reach this plateau of equanimity. “Lord, how did I ever survive? It’s a wonder I’m still alive.”

Both “Right Out Of Left Field” and “Shaking All Over The World” seem to take inspiration from the earliest days of Rock N’ Roll. “Right…” weds sandblasted guitars, Honky-Tonk piano, shaded keys and rumbling bass to a Rockabilly rhythm. Much like John Fogerty’s epochal “Centerfield,” the lyrics use baseball as a metaphor for life’s trials and tribulations, noting “Sometimes life comes at ya right out of left field.” A duck-walkin’ guitar solo seems like a sideways salute to Chuck Berry.

“Shaking…” relies on a relax-fit Bo Diddley Beat, fluttery piano, lush organ colors and sinewy guitar licks. The lyrics offer an easy-going homage to the power of music; “From New York to L.A. to England to France, turn it up everybody, bring on the band, let your hearts rejoice, let your dreams unfurl…from the Queen of England to the Duke Of Earl, they’re shaking all over the world.” A joyful crowd pleaser, features sha-na-na backing vocals and shout-it-out choruses.

Meanwhile, “Casino Winnebego” is anchored by a strutting backbeat, stuttery piano and nettlesome guitar. It comes across like a long-lost Summer of ’78 hit that could sandwich nicely between Jackson Browne’s “Running On Empty” and “Still The Same” from Bob Seeger. Of course, these days, the teens that were weaned on those classic cuts are probably empty-nest AARP RV’ers . So this has the potential to become a 21st century anthem for folks who ‘Saved All their lives so they could come and go…” a spitfire guitar solo on the break signifies that the party isn’t quite over.

Marty’s sonic paintbox turns a surprising shade of indigo for a couple of tracks, “When The Blues Come Around” and “Kentucky Blues.” The former is a mid-tempo groover propelled by swirly ‘60s organ notes, see-saw guitar riffs and an authoritative back-beat. With the urgency of a doomsday prepper, he insists that the blues are an ever-present threat, so it’s best to have that emotional earthquake kit at the ready; “You can be a rich man with diamonds and gold, penthouse suite and fancy cars/Next thing you know you’re in the jailhouse downtown, you better be ready when the blues come around.”

The latter is a soulful, slow-cooked lament accented by smoky harmonica, weepy electric piano and searing guitar. Lovesick and lonesome, he wanders his hometown pining for a girl who is trying to make her musical Dreams come true in L.A.; “I’m blue like the grass that I grew up on, blue like the moon in a Bill Monroe song/Blue like the color of my baby’s eyes, blue like the blue in those Kentucky skies.”

Other interesting tracks include the lithe “Umbrella Lovers” and the teary farewell of “Velvet Chains.” The album closes “Mona Lisa Smiles,” a propulsive and persuasive carpe diem that reminds Us; “In this come-and-go world, life’s so short, it can fade like the Setting sun/We’re no sooner shot out of the gate, then our final race is run.”

Marty co-produced and co-wrote “American Highway” with legendary Producer/musician Jon Tiven, who has worked with everyone from Big Star to the Rolling Stones. He and bassist Sally Tiven play on every track. Other musicians who lend a hand include Anton Fig, Shannon Pollard, Todd Snare, Simon Kirke and Mike Shrieve on drums, Barry Walsh and Tyler Kimbro on keys and Mike Brown on harmonica. Chris Pelcer added strings and backing vocals were provided by Harry Stinson, Chuck Mead, Leroy Brown, Tyler Kimbro, Andreas Werner, Cleveland Dubose and Black Francis.

Maybe there still isn’t a seat at the table for Marty Brown on safe, sanitized Country radio. But that’s just fine. Millions of people get their music from less terrestrial sources these days. The interwebs have allowed like-minded fans to connect and seek out the artists that move them. Marty Brown may never be the flavor of the month, but his music is timeless.