By Eleni P. Austin

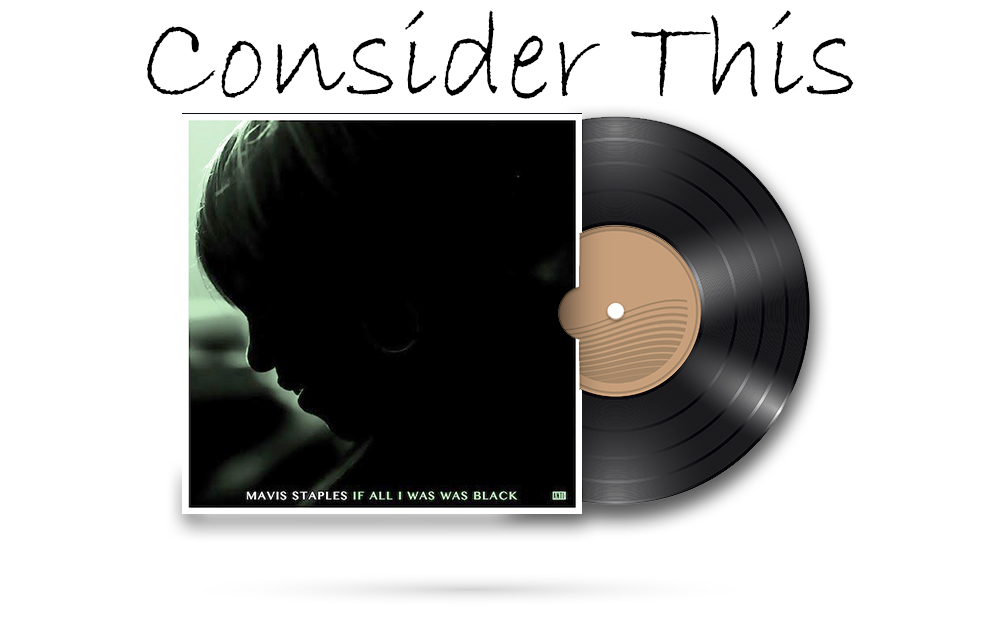

“When I say my life matters, you can say yours does too/But I betcha’ never have to remind anyone to look at it from your point of view” That’s Mavis Staples on the song “Build A Bridge,” wading directly into the Black Lives Matter controversy, but she has been socially conscious before there was a name for it.

Born in Chicago in 1939, Mavis began performing with the Staple Singers in 1950. A true family affair, it included her sisters Yvonne and Cleotha, brother Pervis and father, Roebuck “Pops” Staples. Her dad had been a steel worker and meat packer, originally from Mississippi, the group initially played churches and community settings. They signed their first recording contract in 1952.

Initially, their sound was immersed in traditional Gospel and Blues. During the ‘50s they recorded hit versions of “Uncloudy Day” and “Will The Circle Be Unbroken.” They cycled through a couple of record labels like Checker and Riverside, before landing at Epic. There Pops wrote a song called “Freedom Highway” that became something of an anthem for de-segregation

During the late ‘60s, the Staple Singers began add their spin to more secular songs, adding a soulful and earthy gloss to Buffalo Springfield’s “For What It’s Worth” and Bob Dylan’s “A Hard Rain’s A Gonna Fall.” Each song contained a spiritual subtext that mirrored the struggles of the Civil Rights movement.

In 1968 the Staple Singers signed with the Stax/Volt label out of Memphis, Tennessee. Although Stax never as big as other R&B labels like Motown and Atlantic, they were responsible for introducing the world to seminal R&B acts like Booker T. & The M.G.’s, Rufus Thomas, Carla Thomas, Isaac Hayes, and Mable John. In fact, Atlantic poached several hit makers from the Stax stable like Wilson Pickett, Otis Redding and Sam & Dave.

The Staple Singers achieved their greatest critical and commercial success during their Stax years. From 1968 to 1975 they created eight Top 40 hits with instant classics like “Respect Yourself,” “I’ll Take You There,” and “Let’s Do It Again.” Their sound had evolved into a Soulful alchemy, wrapping themes of self-empowerment and spiritual satisfaction in catchy Soul-Funk melodies.

Despite their musical acumen and time-tested sound, the Staples lost their way a bit during the Disco era. At that point Mavis opted to go it alone and embarked on a solo career. Surprisingly, she only really recorded three albums from the mid ‘70s and throughout the ‘80s.

Luckily, Prince counted himself a major Mavis fan. He signed her to his Paisley Park label, (a boutique imprint distributed by Warner Bros.). He made it his mission to champion her sound to a younger audience, specifically, his loyal fan base. He went on to produce two of her albums; Time Waits For No One in 1989 and The Voice in 1993. Three years later, she recorded an homage to her musical mentor, entitled Spirituals & Gospels: A Tribute To Mahalia Jackson.

The Staple Singers were inducted into the Rock N’ Roll Hall Of Fame in 1999. A year later Pops Staples passed away, succumbing to complications from a concussion. Rather than retreat into her grief, Mavis has managed to reinvigorate her career.

Much like Johnny Cash, Tom Jones, and more recently, Glen Campbell, she enlisted a sympathetic producer and released her 10th solo album, Have A Little Faith in 2004, critics hailed it a glorious return. Three years later she signed with the Anti-label.

An off-shoot of the legendary Punk label Epitaph, Anti-provided asylum for outlier artists who had been marginalized by bigger labels. Everyone from Mose Allison, Neko Case, Merle Haggard, Nick Cave, Marianne Faithfull and Tom Waits have sought refuge there.

Initially, Mavis paired with legendary musician/producer Ry Cooder and released We’ll Never Turn Back, a concept album that included traditional and original songs that revisited the Civil Rights movement of the ‘60s. Universally acclaimed, the record topped myriad critics’ lists. 2010 saw the release of a live effort, Live: Hope At The Hideout her first Studio collaboration with producer Jeff Tweedy, You Are Not Alone.

Of course, Jeff is best known as one of the progenitors of the alt.country/Americana sound that took hold in the late ‘80s. First, he co-founded Uncle Tupelo with Jay Farrar, and then splintered off as the front man for Wilco. He has also spearheaded side projects like Golden Smog and Loose Fur, and recorded a couple of solo efforts.

You Are Not Alone was a potent effort; it even won a Grammy for Best Americana Album. Mavis and Jeff reconvened three years later for the even more assured One True Vine. The songs were a mix of originals, favorites and Public Domain stalwarts, the record struck a balance between the spiritual and the secular. It did well commercially, debuting at #67 on the Billboard Top 200.

While Jeff was busy with Wilco, Mavis enlisted musician/producer M. Ward to shepherd her 15th album, Livin’ On A High Note, it arrived at the beginning of 2016. An all-star affair, it featured contributions from Nick Cave, Neko Case, Jon Batiste, Aloe Blacc, Ben Harper and Bon Iver. Now, after a fairly quick turnaround, Mavis and Tweedy (as she calls Him, rather than Jeff), have re-teamed and the result is her new effort, If All I Was Was Black.

The record quickly gets off the ground with the Swamp-Blues thump of “Little Bit.” Rumbling bass connects with a kick-drum beat, cowbell accents and yowly guitars. Mavis’ measured tones, (matched by call-and-response backing vocals), belie lyrics that zero in on the renewed climate of violence and hostility aimed toward young black men. “Poor kid they caught him without a license, that ain’t why they shot him, they say he was fighting/So…that’s what we were told, but we all know that ain’t how the story goes.” Tensile guitars ripple and ache on the break, acting as a wordless Greek chorus.

All the songs here are written by Tweedy, or co-written with Mavis. The themes seem directly inspired by recent specious claims that we must “make America great again.” These songs assert that America hasn’t lost any of it’s greatness, but we do need to change. Take “Who Told You That,” blistering guitar riffs anchor the track, the insistent and irresistible wah-wah is buttressed by vivid Hammond B3 colors, a chunky back-beat, steadfast bass and electrifying lead guitar. Concise lyrics push back against the idea that change is affected through docile conformity. When instructed “Now hold back, my, my, don’t explode, we don’t want to rock the boat,” Mavis indignantly counters “Who told you that?”

The aforementioned “Build A Bridge” splits the difference between a relax-fit Samba and traditional Cha-Cha-Cha. Over a sultry Batucada rhythm and languid, liquid guitar riffs, the high falsetto backing vocals echo Mavis’ late great champion, Prince. But don’t let the slinky vibe fool you, deadly serious lyrics address the Black Lives Matter crisis and despair over the country’s increasingly

divisive climate; “Look around at our country, at the people we don’t ever see/Standing side by side us divided, lonely in the land of the free.”

“Try Harder” is something of a call to arms. Fuzz-crusted guitars growl and scratch over fluttery keys and a jump-cut rhythm. Here, she acknowledges “there’s evil in the world and there’s evil in me…don’t do me no good to pretend, I’m as Good as I can be.” Rather than accept that status quo, she calls on all of us to “Try harder.”

The wonderful thing about this record is Mavis doesn’t bludgeon the listener with her message, she just nudges us in the right direction. The title track is the absolute epitome of what Otis Redding called “Sweet Soul Music.” Shang-a-lang guitar connects with a loping conga rhythm and tinkling percussion. Building off the Reverend Martin Luther King’s assertion that people should be judged “not by the color of their skin, but by the content of their character,” she asks “If all I was was black, don’t you want to know me more than that?”

“Ain’t No Doubt About It” is a tender testament to Mavis and Tweedy’s friendship. The melody shares some musical DNA with Sly & The Family Stone’s exuberant “Everyday People.” Churchy piano intertwines with Wurlitzer, Country flavored guitar licks and a rock steady beat. The pair trade verses lifting each other up; “Sometimes I feel like talking and then I don’t know what to say/Sometimes I have the answers, but my questions get taken away, that’s when I call your name.”

There’s a deceptive simplicity to “We Go High,” carnival keys wash over rumbling bass lines and a tumbling beat. The lyrics draft off Michelle Obama’s infamous bit of positivity, “when they go low, we go high.” Here, Mavis quietly insists “When they tell their lies, spread around rumors, I know they’re still human and they need my love.”

The album’s centerpiece is “No Time For Crying.” A sweaty Soul-Funk workout, built off a four-on-the-floor back beat and roiling bass. Guitars shapeshift from honeyed licks to coiled rattlesnake menace, the musical piece de resistance is an organ solo that goes from sanctified to swampy. There’s no time to mince words; “People are dyin,’ bullets are flyin’/No time for tears, no time for tears, we got work to do.”

Two tracks return Mavis to her Gospel roots, “Peaceful Dream” and “All Over Again.” The former locks into a rustic back porch groove fueled by a handclap rhythm, Hammond B3 and splayed acoustic riffs. She offers this straightforward epiphany; “Oh I know I did complain, even on Sunny days, I know I moaned about some little things/But I kept my Spirts up, and I set aside enough love to keep us dry when it rains.”

The latter, which closes the record, is stripped down, rueful and Bluesy. Just Mavis’ vocals and bottle-neck guitar. She quietly reflects “Time is slow, and the world gets cold/Sometimes I have Regrets, but I ain’t done yet.”

More than 50 years ago, Mavis and her family were at the forefront of the Civil Rights movement. Marching With Dr. King and lending their talent to the cause. At age 78, she probably assumed those days of intense activism were behind her. But recent events would indicate otherwise.

There’s a climate of hate in this country exacerbated by an Oval Office occupant who receives accolades from a former Grand Wizard of the KKK and is seemingly supportive of White Supremacists. “Driving while Black” has never seemed more dangerous.

As she eases into her golden years, she has made her most powerful album to date. If All I Was Was Black, effectively pays homage to her Chicago Gospel Blues origins. Never preachy or didactic, her words are shot through with love and optimism. Thankfully, Mavis looks forward. She presses on.