By Eleni P. Austin

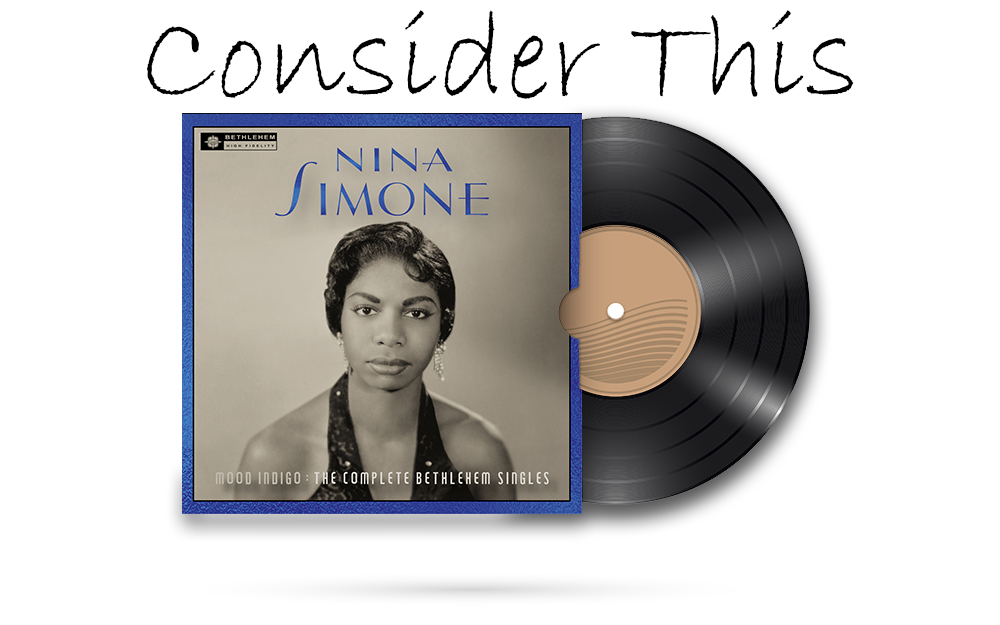

Next month, the late Nina Simone will be inducted into the Rock N’ Roll Hall Of Fame. That’s right, alongside the Cars, Dire Straits, Moody Blues, Bon Jovi and Sister Rosetta Tharpe, the Empress Of Song rounds out the class of 2018. It doesn’t quite fit, but throughout her career, she resisted being pigeon-holed. So in a weird way, it kind of makes sense.

Born Eunice Kathleen Waymon in Tryon, North Carolina in 1933, her prodigious musical talents were recognized almost immediately. She played piano in church and her mother’s employers arranged piano lessons from Muriel Mazzanovich, a piano teacher who concentrated on Chopin, Schubert, Bach, Beethoven and Brahms. She completed her musical schooling at Julliard In the early ‘50s.

When she was denied admittance to the prestigious Curtis Institute in Philadelphia, she began to earn her keep playing piano in a club in Atlantic City. To ensure her devout mother never found out she was performing the “devil’s music,” she took the stage name Nina, (originally a nickname from a former beau), and Simone, from a French actress she admired named Simone Signoret.

After her first club date, the owner insisted that she sing as well as play piano. Her sui generis style incorporated Jazz, Folk, Blues, Gospel, Boogie-Woogie and most prominently, Classical forms. She quickly made a name for herself playing clubs up and down the East Coast. In 1957 she signed with Bethlehem, a subsidiary of King Records. She clashed with label head Syd Nathan when she insisted on complete creative control. Luckily, she had her way and her instincts proved correct, her first single, “I Loves You, Porgy” landed in the Top 20. Her debut album, Little Girl Blue, arrived in late 1958.

For the next couple of decades Nina cycled through a plethora of record labels releasing an astonishing 43 albums. She remained suspicious of the record industry, making her money by staying out on the road, touring relentlessly. In 1961 she married Andrew Stroud and he became her manager. Not long after, the couple welcomed a daughter that they named Lisa.

The business relationship was successful, but Stroud was physically and emotionally abusive. Still, they stayed together. Nina immersed herself in the Civil Rights movement, writing “Mississippi Goddam” as a response to Medgar Evers’ murder and the church bombing that killed four little girls in Birmingham, Alabama. She performed and spoke at the marches in Selma and Montgomery.

Nina was close with both Dr. Martin Luther King and Malcolm X. She was devastated when each leader was assassinated. Songs like “Backlash Blues” and “I Wish I Knew How It Would Feel To Be Free” followed. She co-wrote and recorded the song “Young, Gifted And Black” which was later a hit for Aretha Franklin.

She radically re-interpreted songs associated with Rock N’ Roll artists like the Animals, Bob Dylan, Screamin’ Jay Hawkins, the Beatles, the Bee Gees and the Broadway musical, “Hair.” But by 1970, she felt her outspoken commitment to social justice prompted the music industry to quietly boycott her music. She fled her marriage and pretty much abandoned her daughter, disappearing to Barbados and later settling on the West African coast in the Republic Of Liberia.

Her daughter joined her in Africa, but when Nina became physically abusive Lisa returned to the U.S. to live with her father. Much later they realized that Nina suffered from Manic Depression and a Bi-Polar disorder, but that went undiagnosed for much of her life. With the help of a sympathetic management team she relocated first to Switzerland and finally France. Her music experienced a resurgence in popularity in the late ‘80s when Chanel used her song “My Baby Just Cares For Me” in an ad campaign.

For the remainder of her life she toured consistently and recorded sporadically. She published an autobiography entitled “I Put A Spell On You” in 1992. She quietly battled breast cancer before dying in her sleep a couple of months after her 70th birthday. Ironically, two days before her death, she was awarded an honorary Degree from the Curtis Institute. All these facts are presented in more poignant and elegant terms in the excellent 2015 documentary, “What Happened, Miss Simone?”

Despite the fact that there are approximately 250 different Nina Simone compilations, the BMG label has just added one more; Mood Indigo: The Complete Bethlehem Singles. The album collects and remasters the tracks she originally recorded 60 years ago, most of which appeared on her debut, Little Girl Blue.

The record opens with her first big hit, “Porgy (I Loves You Porgy),” from George and Ira Gershwin’s Folk-Opera, “Porgy And Bess.” Cascading piano notes wrap around the melody before upright bass and brushed percussion kick in. But it’s really just musical foreplay until Miss Simone sings. Her smoky contralto is at once self-assured and diffident as she confesses her love and asks for protection. Even the clunky Black vernacular that Ira Gershwin probably assumed to be authentic Back in the ‘30s can’t get in the way of the depth of her singing, the quicksilver catch in her voice. Many people sang that song before, and quite a few have sung that song since, but Nina Simone owns that song. No debate.

This album is the best of both worlds, featuring solo numbers as well as subtle Jazz trio performances. Nothing feels more intime than Nina behind the piano. Take “Little Girl Blue,” a Rodgers and Hart song originally introduced in the Broadway production, “Jumbo.” The stentorian piano introduction slyly quotes the 17th century carol “Good King Wenceslas” cedes the spotlight to Nina’s supple vocalese. She simply caresses each word as the sadness seeps through, hoping someone will “send a tender blue boy to cheer up little girl blue.”

Nina toggles between brittle apathy and wifely concern on “Don’t Smoke In Bed.” The standard, originally introduced by Peggy Lee in the ‘40s, is cocooned in empathetic piano notes. Slipping out like a thief in the night leaving only a note and a discarded wedding ring she escapes a sour arrangement. Making good on a promise; “I’m packing you in like I said.” Yet, she can’t resist dispensing a little Friendly advice; “Don’t smoke in bed.”

Although Nat King Cole had a hit with “For All We Know” just a few months before, Nina drastically recasts the song, stripping away NKC’s smooth and silky seduction. Instead, she adds an urgency that is equal parts dour and devotional. The piano blends beatific trills and peaking crescendos, that matches her nearly operatic vocals.

As emotionally naked and cathartic as the solo cuts are, the trio numbers offer something of a cosmic exhale. If the solo stuff feels cerebral, the trio tracks are pure id; accompanied by bassist Jimmy Bond (who was later part of the storied L.A. session players dubbed the Wrecking Crew) and drummer Albert “Tootie” Heath, whose musical family included saxophonist Jimmy and double-bassist Percy.

Nina’s take on Ruth Ettig’s signature song, “Love Me Or Leave Me” simply swings. Her opening piano salvo briefly sketches out the melody until bass and drums jump in, kicking the song into gear. Her mien is playful even as she basically tells a guy to sod off unless he can fully commit; “There’ll be no one unless that someone is you, I intend to be independently blue.” On the break her solo is intricate and economical, actually layering the melody with parts of a Bach Fugue.

She completely overhaul’s Duke Ellington’s muted classic “Mood Indigo,” transforming it into jumped up Blues. Bass and drums lock into a speedy shuffle rhythm as Nina’s hands fly over the keys. The rollicking arrangement completely belies sad-sack lyrics like “I’m just a poor fool that’s bluer than blue could be.” Her devil-may-care solo sounds like the work of four hands, not two.

The action slows for the discordant Torch song “He Needs Me.” Drums and bass fade deep in the background as her plaintive vocals and soulful accompaniment take center stage. Meanwhile, “Plain Gold Band” shares some exotic musical DNA with the song “Similau.” The mood is hypnotic, enticing and slightly mysterious.

The balance of the record is made up of three electrifying instrumentals, two of the three, “Central Park Blues” and “African Mailman” are Nina Simone originals. The former is a percolating oharmer that showcases Nina’s nonpareil piano finesse. The latter Opens with a series of classical notes before locking into a tart, Afro-Cuban groove. Here she nearly attacks the keys, pounding one second, feinting and pivoting the next.

The closing tracks are her final singles for Bethlehem, “He’s Got the Whole World In His Hands” and “My Baby Just Cares for me.” On the former, she eschews the sing-a-long quality of the original upbeat hymn, first popularized in the 1920s. Slowing the tempo and underscoring the words gives the track a measure of much needed gravitas.

The latter became her signature song. Although the Walter Donaldson/Gus Kahn standard had been introduced by Eddie Cantor in 1930, Nina made it her own. Cantering piano notes crest over a clip-clop beat, which initially, seems overly simplified. But as the momentum increases, so does the velocity of her playing and the results are simply thrilling. More compelling is her playful vocal style, exuding a sanguine demeanor she rarely exhibited. It’s easy to see why it’s popped up in a plethora of films and television shows, it’s joie de vivre is infectious.

Nina Simone has inspired countless artists. Her influence is especially felt by musicians who accompany themselves on piano. Elton John actually named a piano after her. Diana Krall and Norah Jones are obvious musical heirs. Her songs have been covered by an array of disparate talent like David Bowie, Van Morrison, Nick Cave and Jeff Buckley.

Mood Indigo: The Complete Bethlehem Singles offers a portrait of an artist just starting out, who seems remarkably at the height of her powers. History shows that it only got better. But this was the very beginning.