By Robin E. Simmons

During the pandemic, we watched a lot of movies. Many more older titles than recent ones. We binged on every Alfred Hitchcock movie we could find in chronological order starting with his silent films. In his six-decade career, he made more than sixty movies.

What was most fascinating was not only seeing the evidence of a brilliant cinema artist evolve, but also discovering his obvious personal preferences – especially in composition – he clearly loved trains, reflections, water, birds, eggs, glass, staircases and overhead shots where humans are small figures in an expansive landscape. He liked parallel lines and big structures and formations, both man-made and natural. There was also an element of what can best be described as a sadistic misogyny towards some of his leading ladies in private and on screen. (Morgan Brittany who was a child actor in “The Birds” said that even as a kid, she was aware of the tension between Hitchcock and Tippi Hedren. They are mostly doomed to kill or be killed. But they all suffer.

What was most fascinating was not only seeing the evidence of a brilliant cinema artist evolve, but also discovering his obvious personal preferences – especially in composition – he clearly loved trains, reflections, water, birds, eggs, glass, staircases and overhead shots where humans are small figures in an expansive landscape. He liked parallel lines and big structures and formations, both man-made and natural. There was also an element of what can best be described as a sadistic misogyny towards some of his leading ladies in private and on screen. (Morgan Brittany who was a child actor in “The Birds” said that even as a kid, she was aware of the tension between Hitchcock and Tippi Hedren. They are mostly doomed to kill or be killed. But they all suffer.

All films appeal to our voyeuristic tendency, but in Hitchcock’s films it is a fundamental factor embedded in his movies and likely an extension of his personal life. He was a dedicated people watcher and loved reading about and hearing the gossip regarding UK murders.

On a personal note, I recall once seeing Mr. Hitchcock on the Universal Lot when I was taking a USC cinema class held at the studio.

While waiting for a seminar with director Robert Wise who was running late, I found myself standing outside Hitchcock’s Office Bungalow. No one was around. I was enjoying the morning sun and a cup of fine commissary coffee when Mr. Hitchcock stepped out of his office and stood on the porch enjoying the beautiful day. We stared at each other. I nodded at him and he acknowledged it with a slight head bob.

He looked terrific in his superbly tailored dark. He stood very straight and I could see his rosy plump cheeks, but he looked very fit and surprising handsome. He was not a caricature of himself in any way.

Soon a photographer appeared and immediately took a series of pictures. Hitchcock did not really pose or change expressions but remained very still and serene.

I did notice that one of the collars on his crisp white shirt was bent oddly and very noticeable. I thought the photographer was going to fix the flaw and gestured toward the collar. But Hitchcock waved him away and shook his head. I waved adios and left for the seminar.

Later, I mentioned the collar incident to a friend who worked at Universal. He said Hitchcock’s bent collar was no accident, but was an intentional quirk that Hitch said made his wardrobe choice for the day more interesting because like in his movies, it’s the tiny flaw in an otherwise perfect setting that makes it interesting and creates tension. Consider “Shadow of a Doubt” (1943). Into a perfect Norman Rockwell family appears the sudden intrusion of serial killer Uncle Charlie.

Later, I mentioned the collar incident to a friend who worked at Universal. He said Hitchcock’s bent collar was no accident, but was an intentional quirk that Hitch said made his wardrobe choice for the day more interesting because like in his movies, it’s the tiny flaw in an otherwise perfect setting that makes it interesting and creates tension. Consider “Shadow of a Doubt” (1943). Into a perfect Norman Rockwell family appears the sudden intrusion of serial killer Uncle Charlie.

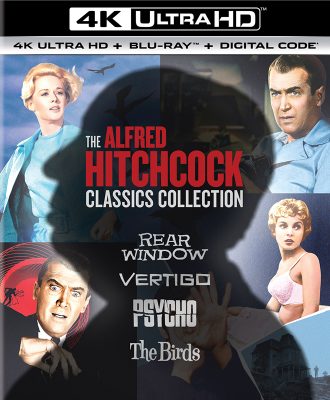

We ended our Hitchcock binge with Universal’s terrific new 4K collection that includes numerous bonus features and two version of “Psycho” (one uncut as originally seen in theaters with additional unseen footage.

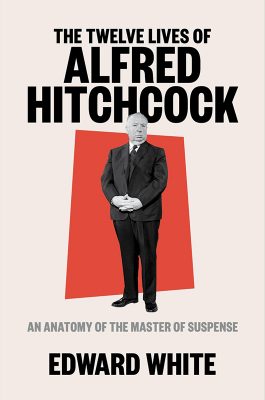

For those who are interested in exploring the fascination of how the Master of Suspense’s personal obsessions and identities informed his movies, there’s a terrific new Hitchcock biography by Edward White (Norton 300 pages).

White’s book breaks down Hitch’s life into twelve distinct personas: ‘The Boy Who Couldn’t Grow Up,’ ‘The Murderer,’ “The Auteur,’ The Womanizer,’ ‘The Fat Man,’ ‘The Dandy,’ ‘The Family Man,’ ‘The Voyeur,’ ‘The Entertainer,’ ‘The Pioneer,’ ‘The Londoner,’ and ‘The Man Of God.’ Recommended.