By Heidi Simmons

—–

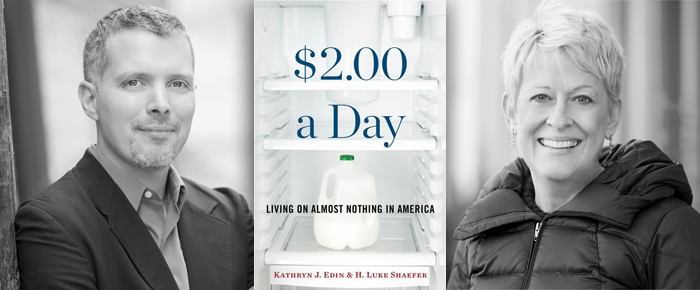

“$2.00 A Day”

by Kathryn Edin & Luke Shaefer

Non Fiction

—–

There may be nothing worse than being poor in the United States. Poverty is at an all time high in our country. In $2.00 a Day: Living on Almost Nothing in America, (Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, 240 pages) authors Kathryn Edin and Luke Shaefer spell out the precarious lives of those who struggle to exist on only a couple of dollars each day!

If you think this book could serve as a guide for penny pinching, you will first be disappointed and then relieved you even have pennies to pinch. This book is about the horror and tragedy of what is happening to the working poor in America

Two dollars a day represents a per person average. That means if the household consists of a mother and her two kids, the amount is six dollars – that’s the amount left after payday and bills. However, the mother and her kids don’t actually have that amount as cash money. At the end of the month, after paying rent and utilities, transportation to and from work, there is basically little to nothing left for food.

Edin is a sociologist who for the last several decades has studied the poor and poverty in major American cities. When she revisited cases from a decade earlier, she noticed conditions are worse today. She wanted to know why.

Teaming up with statistician and social worker Shaefer, the two hoped to figure out how to get an accurate picture of the new poor. How were they surviving? And on how much?

They discovered that the level of poverty was so deep – the destitution so great, they had to use the World Bank’s metric of global poverty model in the developing countries! A shocking revelation previously un-thought of in the US.

The official poverty level line in the US for a family of three is about $16.50 per person, per day. The government’s designation as “deep poverty” is $8.30 per person, per day. Edin and Shaefer are the first to look at Americans who fall below the $2 per day.

In the research, they found that the $2 a day did not discriminate by family type or race. The rate of growth (of the poor) is highest among African Americans and Hispanics, but nearly half of the $2 a day poor are white.

The authors follow eight families in cities around the country who live under the $2 mark. This is where the book’s narrative comes alive and the poor become very real.

Modonna and her 15-year-old daughter lose their apartment and live between family and shelters. Modonna had a minimum wage job for eight years with the same company. Until one day her cash register came up short $10 and they fired her. The employer later found the money, but did not rehire her or even apologize. This sent her and her daughter into a downward spiral when Modonna could not find another job.

Jennifer and her two children live in a homeless shelter. When Jennifer had a job, she traveled hours taking two buses to get to work. She worked for a company that cleaned up construction and foreclosure property. It paid her $8 an hour. When Jennifer got sick, she kept working. The condition of the Chicago area’s abandoned properties she was cleaning for the banks were intolerable – mold, human feces and freezing temps. But she kept at it — until she collapsed. Even though she was one of the companies best workers — and the longest — they fired her.

Susan gets up early everyday to apply for jobs. She sends out applications via her refurbished $30 iPhone – her only possession. She must constantly purchase minutes, which quickly run out. But at least she has access to Internet service with the phone. This gives her an advantage. Most poor have no access to a computer, let alone Internet service.

She applies over and over to Walmart, a tedious process that has become traumatic for her because of the confusing, psychological questions. When she finally breaks down and goes to the welfare office for help, she waits in a long line for hours and hours to only be told she needs to come back another day because the quota was already filled. She won’t go again because she believes there is no help.

Rae worked for Walmart and was “checker of the month” two times. When she couldn’t make it to work because she didn’t have transportation, she was fired. Rae and her baby daughter (an unexpected pregnancy after antibiotics neutralized her birth control) live with relatives. After she paid her rent, utilities, bought diapers and food, she had no cash left. The car she shares, and fills with gas, was drained by the other user.

Each person in the book has a heartbreaking story. It is bad luck at best and exploitation at worse. The poor cannot get a break. Low-wage employers see these people as dispensable labor.

The authors spend time on the history of welfare and the decline of the system. They point to a survey, which concludes Americans don’t hate the poor, they hate welfare. Even so, today fewer people are on welfare than at anytime in history when they need it most.

The number of American families living on $2 a day is one and half million households and includes three million children.

The authors offer ways to change this desperate and sad situation. The most obvious solution is jobs! This book is well organized and succinctly written. It made me furious and feel helpless. This is an important read if you want to understand our country’s current economic truth. When the poor are poorer than ever, the problem points to something much greater.