By Eleni P. Austin

“I lit my purest candle close to my window, hoping it would catch the eye of any vagabond who passed it by/And I waited in my fleeting house.”

That’s Tim Buckley singing his gorgeous lament, “Morning Glory,” and it sort of sums up his brief, flickering career as a musician.

Preternaturally talented, handsome, stubborn, idiosyncratic, sometimes self-sabotaging, he should have been a superstar. Over the years he attained a cult following, but most people have never heard of him.

Timothy Charles Buckley III was born in Washington, D.C. on February 14th 1947. His father was a highly decorated WWII veteran who came from a family of Irish immigrants. His mother, Elaine was of Italian-American descent. Tim spent his childhood in the small town of Amsterdam, in upstate New York. It was there that his mother ignited his passion for progressive Jazz, introducing him to the music of Miles Davis.

By the mid-fifties, his family moved to the small Los Angeles bedroom community of Bell Gardens. At this point his grandmother exposed him to singers like Bessie Smith, Frank Sinatra, Billie Holiday and Judy Garland. Meanwhile his father introduced him to the rural charms of Hank Williams and Johnny Cash. When Folk music began to gain traction in the early ‘60s, young Tim taught himself the banjo and formed a series of groups inspired by the Kingston Trio.

Attending Buena Vista High School, Tim was popular and athletic, running for and winning school office and joining the junior varsity football team as a freshman. By the end of his sophomore year he quit football and began concentrating all of his energy toward music. It was around this time he began playing with Larry Beckett and Jim Fielder first as the Bohemians and then the Harlequin 3.

Tim’s family soon relocated to Anaheim, 50 miles south of L.A. At this point his parents separated, his father had become a volatile presence, possibly the result of suffering serious head injury during the war along with a severe work-related injury. Laser focused on music, and somewhat disillusioned, he cut school and began dating Mary Guibert. They were married in late 1965 when Mary believed she was pregnant. They soon discovered it was a false pregnancy.

The marriage was immediately tumultuous, but soon Mary was pregnant for real. In reality, Tim was much too young to handle the responsibilities of marriage and impending fatherhood. Pretty soon he bolted. They divorced a month before his son Jeff was born in late 1966. They only ever met once, when Jeff was eight years old.

Following a brief interlude at Fullerton College, Tim concentrated completely on his music career. He emerged from the same Orange County Folk scene that spawned Jackson Browne and the Nitty Gritty Dirt Band. Jimmy Carl Black, drummer for Frank Zappa’s Mothers Of Invention caught one of Tim’s performances at a club and recommended their manager, Herbie Cohen, check him out.

Cohen quickly signed him and got him a gig at the Nite Owl Café in Greenwich Village. He also financed a six song demo which they sent to Elektra Records president, Jac Holzman. Immediately grasping his potential, Holzman signed Tim to the label. His self-titled debut arrived in October, 1966. An audacious introduction, it spotlighted his multi-octave voice and featured a clutch of surprisingly sophisticated songs, most of which he had been while he was in high school. It received rave reviews and achieved respectable sales.

Less than a year later, he returned with Goodbye And Hello. Equally as assured as his debut, the album added touches of Psychedelia to the mix and Jazzy textures that foreshadowed future efforts. Both “Goodbye…” and it’s follow-up, Happy Sad, (released in the summer of 1969), were produced by Jerry Yester. A multi-instrumentalist, Jerry began his career with his brother Jim as the folk duo, the Yester Brothers, and later joined the New Christy Ministrels and Modern Folk Quartet.

Jerry Yester’s even-handed production provided ballast for Tim’s jazzier flights of fancy. Released at the height of his popularity, “Happy Sad” was his highest charting album, reaching #81. This marked the beginning of him using his voice as an instrument. His increasing experimentation began to alienate his fan-base.

Tim had entered his most prolific period, simultaneously writing and recording two albums: Blue Afternoon, which was released through Straight, (Herbie Cohen and Frank Zappa’s boutique label), arrived in late 1969. Lorca, named for the Spanish poet, Federico Garcia Lorca, went through the regular channels of Elektra Records and came out in May, 1970. Abandoning the melodicism that defined his earlier music, he pushed the boundaries, veering into Avant Garde territory.

Fully extricated from his Elektra contract, Tim re-entered the studio in September, 1970 and recorded what he considered his masterpiece, Starsailor. Released two months later, it contained his best known song, “Song To A Siren.” The tune was subsequently covered by This Mortal Coil, Robert Plant, John Frusciante and Bryan Ferry.

Tim stubbornly continued to follow his muse, and became increasingly frustrated by his lack of success. He began to rely heavily on drugs and alcohol. Although he had remarried and adopted his wife Judy’s son, Taylor, he characterized his final three albums, Greetings From L.A. (1972), Sefronia (1973) and Look At The Fool (1974), as “sex funk” music.

On June 28th, 1975, following a well-received concert with his band, Tim celebrated, apparently all weekend. When a friend produced a bag of heroin he indulged. He had an adverse reaction and friends brought him home. They laid him on the floor and later they moved him to the bed. Checking on him, his wife Judy discovered him blue and not breathing. Paramedics were called, but he was pronounced dead. The coroner’s report listed cause of death as acute heroin/morphine and ethanol intoxication, resulting in an overdose.

While Tim never achieved stardom in his lifetime, since his death, his legacy and status has only grown. Burnished in part by his son, Jeff’s brilliant but truncated career in the early ‘90s. Possessing his father’s innate musicality, Jeff made a huge splash in 1994 with his only studio album, “Grace.” In Memphis to record his sophomore effort, he went for a swim in Wolf River Harbor, a slack water channel in the Mississippi River. He was caught in the wake of a passing boat and accidently drowned. He was barely 30 years old, outliving Tim by two years.

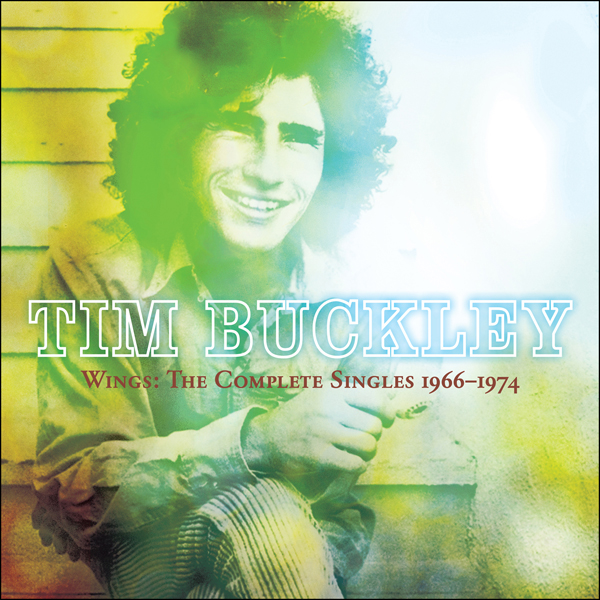

In the years since his death, Tim’s records have drifted in and out of print. Luckily, the folks at Omnivore Records have found a way to assemble his most accessible music in a new compilation entitled Wings: The Complete Singles 1966-1974.

In the years since his death, Tim’s records have drifted in and out of print. Luckily, the folks at Omnivore Records have found a way to assemble his most accessible music in a new compilation entitled Wings: The Complete Singles 1966-1974.

The first four tracks come from his self-titled debut. Wings epitomizes the perfect ‘60s Folk song. Lush and sylvan, it opens tentatively, propelled by a shuffle rhythm, ringing guitars and Tim’s breathtaking tenor. Cushioned by a soaring string section the lyrics seem to offer comfort and counsel to a woman trapped in the throes of unrequited love.

“Grief In My Soul” lands somewhere between a Dylan-esque ramble and Monkees Folk-Pop, the buoyant melody and instrumentation belies the lyrics’ teen-age dramaturgy. Ballsy guitar collides with barrel-roll piano and a jaunty backbeat as Tim soul-shouts “I’ve got ten thousand troubles, a million woes/I got grief in my soul that nobody knows.”

“Aren’t You The One” unspools like a Madrigal. Over a martial cadence, tambourine accents and chiming guitar, Tim’s stentorian vocals sail over the melody, blunting his withering criticism of a woman who belittled him in the past. Meanwhile, “Strange Street Affair Under Blue” is his first attempt at sonic exploration. Beginning with a pronounced rhythm that flows like a Taxim, (which is traditionally used in Greek or Middle Eastern Folk Dances), it slowly accelerates and downshifts in a series of aural switchbacks. Guitar riffs pivot between subtle flickerings and frenetic fretwork. Lyrics like “You wish to catch and cage me now,” seem to take aim at his (almost) ex-wife and the false pregnancy that later became real.

Two tracks, “Once Upon A Time” and “Lady, Give Me Your Key,” have never appeared on any Tim Buckley collection before, (“Once…recently appeared on a boxed set from Rhino Records entitled “Where The Action Is,” spotlighting Los Angeles music from 1965-1968). The former is a Psychedelic raver that wouldn’t seem out of place on an album from Jefferson Airplane or Iron Butterfly. A rollicking work-out, its anchored kronky guitar, a galloping back-beat, bleating horns and kaleidoscopic keys. Tim’s powerful vocals crest over the calibrated chaos.

The latter is accented by Ragtime piano notes, jangly guitar, tumbling rhythms and a hint of harpsichord. Tim’s sanguine vocals match the pithy melody. On the surface, it seems like he’s looking for a little sexual healing, but during the swinging ‘60s, “key” was also code for kilo, which was a measurement for certain herbal refreshments.

On the four tracks culled from Goodbye And Hello, Tim continues to expand his musical horizons. “Morning Glory” is a piano driven ballad that folds in liquid arpeggios and honeyed harmony vocals. It’s quite possibly his most ethereal melody.

With over pulsating keys, and harpsichord filigrees, the U.K. b-side, “Knight Errant,” offers up Elizabethan imagery as a camouflage for more salacious activities. Lyrics like “I love her upstairs, I love her downstairs, but I love my lady’s chamber” aren’t particularly cryptic.

The U.S. flipside is “Once I Was.” A tear-drop rhythm and lonesome “Home On The Range” harmonica link up in ¾ time. The melody shares some musical DNA with Fred Neil’s “Dolphins.” The opening couplet, “Once I was a soldier, I fought on foreign lands for you” evokes imagery of the Vietnam war, (which was raging at the time). But the lyrics are really a wistful recollection of simpler times; “And sometimes I wonder, just for a while, will you ever remember me?”

Congas and piano intertwine with organ fills and rippling guitar on “Pleasant Street.” Alternating between Jazzy verses and Psychedelic choruses, it includes thoroughly ‘60s stream-of-conscious non sequiturs like “All the stony people walking ‘round in Christian licorice clothes, and I can’t wait for Pleasant Street.”

“Carnival Song” is exactly as it should be. Fluttery waltz rhythms wash over authentic carousel calliope sounds and Tim’s sing-song vocals. His mien is mournful as he strips away the midway façade, revealing the shabby reality.

Because his next three albums, Happy Sad, Lorca and Starsailor featured his purest and most experimental work, the shortest songs clocked in at over six minutes. None of them were released as singles, so the action skips from 1967 to 1969, landing on two tracks from Blue Afternoon.

“Happy Time” is a playful confluence of Jazzy guitar chords, thrumming bass and a tippling hi-hat rhythm. The lyrics are a paean to the pure joy of creating music; “Ah, it’s a happy time inside my mind, when a melody does find a rhyme/Says to me I’m comin’ home to stay.”

“So Lonely” is a sad-sack Blues pastiche. Here, Tim bemoans his lack of companionship; “Oh, I don’t get no letters, nobody calls, nobody comes ‘round here no more/No pretty ladies, no pretty boys, nobody comes ‘round my door anymore.” The arrangement features fluid guitar licks, feathery rhythms and a gauzy vibes solo.

The Greetings From L.A. singles: “Move With Me,” and “Nighthawkin’” Are Tim at his most soulful. The former is a wicked ramble that recalls a night at the “Meat Rack Tavern” in the company of a “big ol’ healthy girl.” The track is powered by gritty guitar, rollicking piano runs, licentious backing vocals and a soulful horn section.

The latter is a combo-platter of Afro-Cuban rhythms and choogling Rock N’ Roll. Tim reveals a gift for straight-forward narrative, spinning a tale of taxi cab bravado. (Literally the obverse of Harry Chapin’s lachrymose story-song “Taxi, which arrived three years later.)

The songs from Safronia, include the Prog-Rock see-saw of “Quicksand,” the Soul-shouter workout of “Stone In Love” and the Bluesy “Honey Man.” As intriguing as the melodies and arrangements are, Tim’s single-minded pursuit of carnal knowledge feels clumsy and awkward. What saves this set is his cinematic version of Fred Neil’s Folk-Jazz touchstone, “Dolphins”

The album closes out with his final two singles, “Wanda Lu” and “Who Could Deny You.” Taken from 1974’s Look At The Fool, each song presents a different side of Tim Buckley. “Wanda Lu” is a conscious homage to the Kingsmen’s indecipherably salacious Rock classic, “Louie, Louie.” From the raucous rhythms to the shout-it-out chorus, it’s a long way from the pastoral grace of “Morning Glory.”

Finally “Who Could Deny You” is equal parts ambitious and idiosyncratic. It begins like a sophisticated Cole Porter Cha-Cha-Cha with Tim crooning and caressing the lyrics. Lush to the point of fecundity it suddenly shapeshifts into an Rockin/Soul revue, replete with call-and-response vocals, tickly piano runs, spiraling synths (that pre-sage Steve Miller’s “Fly Like An Eagle” intro by two years), arch guitar solos and pummeling drums. It’s a dizzying end to a wide-ranging collection. It’s interesting to note that what Tim Buckley and his record label regarded as his most commercially accessible songs still feel light-years ahead of their time. Wings: The Complete Singles 1966-1974, opens the door to a rich musical legacy ripe for (re) discovery.