By Eleni P. Austin

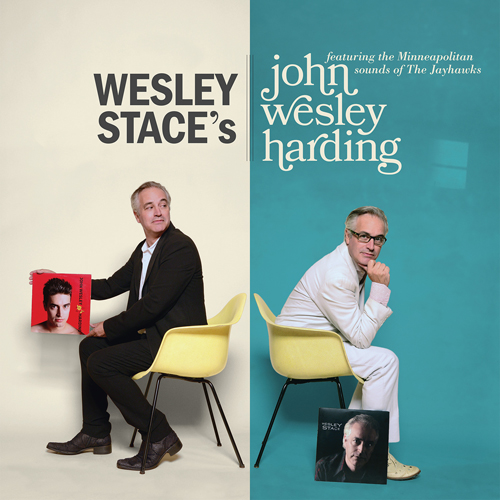

If it were possible for Elvis Costello, Bob Dylan and Nick Lowe to have a musical love child, his name would be Wesley Stace. Wesley’s music embodies the erudite wordplay of Elvis, the biting social commentary of Bob and the pure pop songcraft of Nick. Plus, like the first two, when he began his career in music, he adopted a stage name, John Wesley Harding.

Wesley Harding Stace was born in Hastings, East Sussex, England in 1965. Both of his parents were school teachers, each had musical talent, his mother had been a mezzo-soprano opera singer and his dad played Jazz piano. Although he grew up loving music and even began playing in local pubs at age 17, Wesley was headed toward a career in academia.

Studying English Literature at Cambridge University he earned high undergraduate grades and started working toward a PH.D in political and social theory. But the siren song of music was too great. He set his academic goals aside and began concentrating exclusively on music. Figuring he would return to his scholarly pursuits at some point, he assumed a nom de rock, choosing the name John Wesley Harding, (an homage to a seminal Bob Dylan record).

In the summer of 1988, he performed a set of original music in London. Rather fortuitously, a number of music industry people were in attendance. Soon he was opening for the Hothouse Flowers in the U.K. and acclaimed singer-songwriter John Hiatt in the U.S.

Rather than record a traditional studio debut, Wes signed a one-off deal with the British indie Demon Records and released a live effort, “It Happened One Night.” Recorded at the small Wheelhouse Club in London, the effort showcased his protean songwriting skills as well as his razor-sharp wit. The cognoscenti were quick to note the similarities to Elvis Costello and Bob Dylan and the major labels took notice. He quickly signed with Sire, home to the Pretenders, the Smiths and k.d. lang.

Wesley got together a band, which he dubbed the Good Liars. The line-up included bassist Bruce Thomas and drummer Pete Thomas, (no relation), formerly of Elvis Costello’s backing band the Attractions. (This ensured that the Costello comparisons continued). His studio debut, Here Comes the Groom arrived in 1989, accompanied by great reviews and modest sales.

He made two more albums for Sire, The Name Above the Title in 1991 and Why We Fight 1992. Although he continued to garner good notices and his audience increased, Sire was unsatisfied by his low sales. They parted company and his last three ‘90s efforts, John Wesley Harding’s New Deal, Awake and Trad. Arr. Jones, (a tribute to venerated English Folk singer Nick Jones) were each released on Rhino Records and Zero Hour, respectively.

A couple of years after the 21st century arrived, Wesley popped up on the Mammoth label with The Confessions Of St. Ace, (a clever pun on his real surname, Stace), and continued to make albums at a prodigious pace. Adam’s Apple appeared in 2004, Songs Of Misfortune, credited to his band the Love Hall Tryst came out in 2005, a collaboration with the Minus 5, Who Was Changed And Who Was Dead, was released in 2009, and The Sound Of His Own Voice hit in 2011.

By this point, he had released 12 studio albums, three EPs and five fan club recordings. He had also begun a second career as a University professor and wrote four well-received novels. In 2013 he retired the John Wesley Harding moniker and released the album Self-Titled. Now, in collaboration with alt.country pioneers the Jayhawks, he has released his 14th record, playfully entitled, Wesley Stace’s John Wesley Harding.

The album opens with the one-two punch of “I Don’t Want To Rock ‘n’ Roll” and “You’re A Song.” Over descending piano notes a sturdy back-beat and jangly guitar chords, Wesley effortlessly slips into the skin of life-long music fan, who’s excitement and passion has waned. He casually announces “I’m hangin’ up my leather jacket, my backstage passes and my laminates/Take my name off of the list, I’ve seen the show, I’ve got the gist and I don’t want to Rock ‘n’ Roll no more.” He goes on to list myriad reasons he won’t be rock ‘n’ rollin’ but the whipsaw electric guitar solo that closes the song signals he’s had a change of heart.

The album opens with the one-two punch of “I Don’t Want To Rock ‘n’ Roll” and “You’re A Song.” Over descending piano notes a sturdy back-beat and jangly guitar chords, Wesley effortlessly slips into the skin of life-long music fan, who’s excitement and passion has waned. He casually announces “I’m hangin’ up my leather jacket, my backstage passes and my laminates/Take my name off of the list, I’ve seen the show, I’ve got the gist and I don’t want to Rock ‘n’ Roll no more.” He goes on to list myriad reasons he won’t be rock ‘n’ rollin’ but the whipsaw electric guitar solo that closes the song signals he’s had a change of heart.

As those power chords resolve, it’s as though someone’s flipped the radio dial. Chiming acoustic riffs trickle through and the melody locks into the twangy two-step of “You’re A Song.” The lyrics take us through a tentative courtship that blossoms into love. But a lonesome lap-steel solo underscores a betrayal; “Now you found another singer, but every cloud is silver-lined/’Cause he knows that you are perfect and he knows that you were mine, You’re a song, but someone else is singing you now.”

Wesley takes a novelistic approach on several tracks. On the Cowbell Funk of “For Me And You,” a tick-tock rhythm and roiling bass lines connect with crunchy guitar riffs. Superficially the lyrics portray a couple at cross purposes, but truly the song is a message of tolerance, honoring contrasting points of view. “I pray in a different way it’s clear that you don’t approve, yesterday I made up my mind to stay-but today I’d be happy to move/You can have the last word if you like, as I lace up my shoes/And this world is big enough for me and you.”

Fuzzy guitars blend with sweet harmonies on “Better Tell No One.” The opening couplet offers some vivid imagery; “The baby fell out of the swing, the three of us just watched her fall, then when I woke well, there wasn’t a baby at all/I didn’t want you to meet and there we all were in the lift, he knelt at your feet and he gave you a house-warming gift, better tell no one your dreams!”

“The Wilderness Years” weds cyclonic guitar riffs to a rollicking rhythm and pounding piano. Droll double entendre gives a new twist to Adam and Eve’s origin story. Initially pissed that he’s cast out of the Garden Of Eden, Adam begins to enjoy being exiled in the wilderness; “You threw me out of your Eden, now I’m on gardening leave, I copped to my crime, but I didn’t like your timing, days before Christmas Eve/…but I like it here, there’s less apple less snake, more give and take, turns out I like playing it by ear.”

Finally, “Hastings Pier” is a stately stroll down memory lane. Flickering piano notes, flange-y guitars and brushed percussion recall the gravitas of the Who’s Quadrophenia songs; the arrangement shapeshifts from spatial to Prog-y. The lyrics offer a lovely homage to the East Sussex pleasure pier built in 1872 and burned to the ground in 2010.

From the ‘60s through the ‘90s plenty of concerts took place; “the Who, the Rolling Stones, Pink Floyd, Syd Barrett’s final show,” and Wesley also experienced his own musical growing pains there; “Hastings when I was younger, amusements in the summer, a holiday from boarding school, busking ‘round memorial/There I plied my trade to general disdain, a handful of change to put in the machines on Hastings Pier.”

Three songs are tart encomiums to a longtime relationship. On “How To Fall”, rippling acoustic arpeggios match up to a clickity-clack shuffle rhythm, electric guitar filigrees and warm organ colors. Here he confesses “I’ve forgotten how to sleep, how to change the sheets, I’ve forgotten standing still, and I wonder when I will/Ah, but that’s not all, I’ve remembered how to fall, I’ve remembered how to fall in love with you again.”

“Audience Of One” fuses sun-dappled acoustic guitar, plaintive piano and pliant pedal steel. The lyrics paint a poignant portrait of singer-songwriter facing lackluster crowds, but he maintains motivation by imagining he’s performing only for his significant other; “I’ve played shows where those onstage outnumbered those who paid, but I’ve never had more fun than playing to an audience of one.”

With “Remember Me,” Wesley confronts issues of mortality and worries he won’t leave a legacy. A swirly and serpentine guitar solo underlines his anxiety; “Don’t forget my fate, don’t forget my fate, it’s getting late, it’s getting late.”

Other interesting songs include the bucolic lament “What Belongs To You” accented by latticed piano and mellotron. He also includes a cover of the Soft Rock obscurity, “Don’t Turn Me Loose,” originally recorded by Greenfield & Cook. The album closes with its most ambitious cut, “Let’s Evaporate.” Here spacy synths collide with a propulsive back-beat, a wash of keys and stuttery guitar. The lyrics remind us essentially we are all just air and water; “We are vapor you and me, a disappearing act/Rising in the atmosphere and falling back.” The tempo downshifts on the instrumental coda, closing in on some wah-wah guitar, as the melody drifts off in space.

This is a nearly perfect record, the only thing missing is Wesley’s version of Bob Dylan’s epochal “Tambourine Man.” Rechristened “Tangerine Man,” his updated lyrics reflect the shift in White House occupancy, making reference to coral coloring, the anatomical significance of tiny hands and the suspect device affixed to his head; “Hey Mr. Tangerine man what’s that on your head, is it alive or is it dead/Do you keep it on in bed, how often is it fed, we’re all dying to take a peak to see what’s under it…”

The Jayhawks add color to Wesley’s commentary, always complimenting, but never overshadowing him with their instrumental prowess. Hopefully this musical partnership will continue.

Although he will probably always be compared to musical forefathers like Costello, Dylan and Lowe, nearly 30 years on, the artist formerly known as John Wesley Harding long ago emerged from their shadows making music that is wholly his own.