By Aaron Ramson

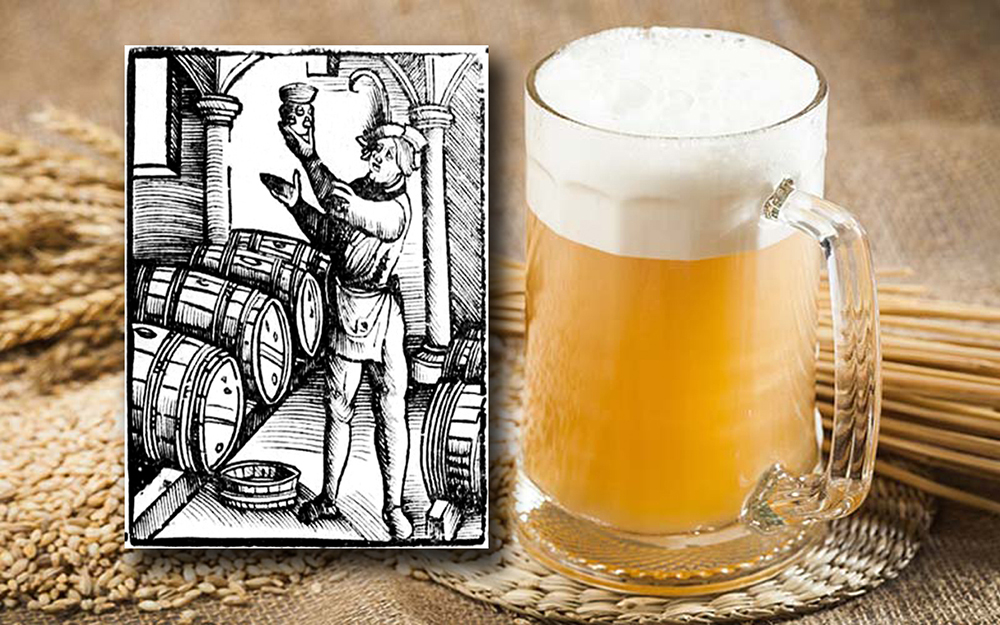

When ancient Sumerians wrote down the first recipe for beer (as covered in the very first installment of Brewtality, which I don’t even own. Do you have a copy that you want to give to me?), it was more of an idea than a strict doctrine. Through centuries of war, trade and diplomacy, the Sumerians spread their knowledge of brewing to other lands and cultures, most notably the Egyptians, who credit the building of the great pyramids to the consumption of beer. Beer was seen as a nourishing and strengthening liquid that juuuuuust so happened to have the great side effect of getting you buzzed if you had more than a couple of hieroglyph-covered clay pots of the stuff. As human ingenuity would have it, beer recipes began to contain more and more ingredients whose purposes were the enhancing of both flavor and buzz. By the time Egypt, as well as most of the known world (aka Europe, Asia, and Africa. That was pretty much the known world back then) was absorbed into the Holy Roman Empire, beer was a staple amongst mankind, and almost anything that didn’t kill you could be put in it.

By 1516, this became problematic.

Bread makers began bitching *in nasally, whining voice*, “the beeeeer people are using aaaallll our wheat and we don’t have any floouurrrr”. And on top of that, the clergy was getting pissed that certain brewers were putting hallucinogenic herbs into their brew kettles and making pagan beer. Pagan beer, people!! Something had to be done. So, the Duke of Bavaria put his twinkle-toed foot down (I imagine him wearing those shoes with the toes that curl and point up, looking like one of Santa’s elves or a Dr. Seuss character), and enacted the purity law of 1516. According to this new law, ain’t shit wasn’t gonna go into beer anymore except barley. Oh, and hops, since those weren’t considered pagan. And water, definitely water. They didn’t know about yeast yet, so that wasn’t part of the original doctrine. But if it wasn’t barley, hops, (yeast) or water, it couldn’t go into beer anymore. So the bread people got all the wheat to themselves, the clergy got to double high-five each other for making sure beer wouldn’t get you high anymore, and the Kottbuser became illegal to brew.

What the f#%k is a Kottbusser, you ask? German brewers from the town of Cottbus had developed a style of beer that included wheat, oats, honey, and molasses, and it’s sweet, smooth, and nutty flavors were popular amongst the beer drinkers of the early 1500’s. The ordinance of 1516’s purity law spread from Bavaria to Germany, Poland, and beyond, effectively ending the brewing of beers like the Kottbusser.

While the purity law of 1516, adopted by the Germans and named the Reinheitsgebot (I’m just gonna be real here and admit that I don’t have any idea how to pronounce that. Ryne-hait-sgay-bot? That doesn’t sound right at all. And if I’m saying it right, sheesh that’s an awful sounding word. No wonder German has never been accused of being the language of love), made bread makers and the clergy happy, it effectively hamstrung innovation and creativity in brewing. Styles like the Kottbusser were lost to history, and only revived due to the passion and creativity of craft brewers. While it’s remained a bit of a novelty stateside, several brewers have now attempted recreating the style, and yours truly can be counted amongst them.

Historic literature is hard to come by for this style, and what I mean by that is that my five-minute google search turned up little more than a couple of vinepair.com articles referring to it as a “an obscure beer worth a try”. Totes useless info, but I put my imaginary lederhosen on and concocted my own recipe. Starting with the base of a classic hefeweizen, I added flaked oats and flaked barley to my mash, creating a deliciously cereal smelling wort when boiled. I gave it an American twist by using Mount Hood, Willamette, and US Tettnanger hops for a balanced bitterness that still leans the beer slightly to the malty side. Finally, near the end of the boil, orange blossom and avocado honeys, as well as black strap and fancy molasses were added to the kettle. I decided that a hefeweizen or even American ale yeast would be too much for a recipe with this much subtle character, so I went rogue and used Zurich lager yeast to ferment a beer that leaves no character other than the flavors imparted by wheat, oats, honey, molasses, and hops.

The result so far is a unique tasting and refreshingly balanced beer. Lacking the sweetness that is described in the heirloom style, my Kotbusser instead has a doughy, nutty, lightly tart flavor that’s anchored by firm hopping. By the time this article goes to print, I’ll have it kegged and on tap at the brewery where I work, Brewcaipa Brewing Co in Yucaipa, CA. It’s part of my American Oktoberfest lineup that also includes a 7.5%, Imperial strength Marzen, as well as a Helles lager that’s perfect for quaffing steins of. Come say hello and raise a pint with us. Prost!