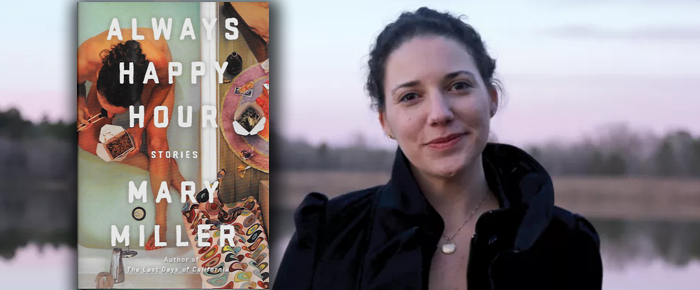

By Heidi Simmons

—–

Always Happy Hour

by Mary Miller

Stories

—–

Does happiness come naturally, or does it take a conscious effort to be happy? Some women find happiness to be more elusive when they surrender control to the men in their lives in Mary Miller’s stories Always Happy Hour (Liveright Publishing, 256 pages).

Most of author Miller’s 16 stories are told in the first-person voice, which gives the reader a very intimate perspective into the characters’ weaknesses.

The title story “Always Happy Hour,” tells the tale of a young women, Alice, a high school teacher and a grad student, who is dating a man, Richie, who appears to have unlimited funds, but doesn’t have a job.

Richie is divorced with a four year-old son. Alice does her best to feign interest in the child, because she isn’t pretty and knows that’s the best way to stay in good with her boyfriend. In some ways, Alice enjoys playing with the boy, taunting him and acting childish.

In Alice’s eyes, the relationship with Richie is certainly not a match. He still sees his ex-wife and is friendly with past girlfriends. He is a local boy, and she is an outsider. But, Richie is kind and generous, which makes Alice even more certain they have no future.

“Where All of the Beautiful People Go” is a story of two unlikely friends. The narrator admits to being Aggie’s friend only because she gives her free pills. The woman telling the story worries that her boyfriend will break up with her if he knows she’s taking pills, so she hides them and hangs out with Aggie.

Aggie is a decade older, married with two young boys, whom Aggie does not pay enough attention to, and when the narrator –- her friend — is around, the kids love to play with and annoy her. She judges the boys. One is good looking and will never have a problem in life, although he’s not too bright, while the other child is clever and manipulative, which she believes will serve him well.

Aggie is a petty thief and the narrator struggles to keep the secret from George, Aggie’s older husband. The narrator contemplates how her relationship with Aggie started, and why, then wonders how she even remains friends with her.

“Hamilton Pool” is one of the few stories told in the third-person. Darcie is a college dropout and is dating Terry, a handsome, tattooed ex-con. The two have no work and Darcie’s parents have stopped supporting her. Terry promises he will never leave her and that someday they will have a big house, set back from the street, and two beautiful children.

Darcie asks him how he plans to do that when he doesn’t have money to even take her out for a taco. She likes the apartment and neighborhood they live in because it is jumbled, messy, dangerous and colorful. When she needs to go to the doctor for female problems, they must take the bus because all the money they have together is barely $12.

“Proper Order” finds a graduate student/teacher and scholarship recipient living in the magnificent home of a famous writer who donated it and its contents to the university. When she entertains her undergraduate students, she finds herself attracted to one of the boys and can’t decide if she should have sex with him, but loves the effort he makes to seduce her.

If there is a common denominator in these stories, it’s that the women have low self-esteem, self-loathing tendencies, and think men will destroy you before they can save you — neither of which is good.

However, the women are not stupid. The characters are most often somewhat educated or in graduate school, yet they find themselves victims of their own poor choices. The women seem to wallow in loss and loneness and solve their problems by ignoring them or self-destructing.

Author Miller delivers an authentic setting in Texas and the south where the reader can feel the humidity and stagnating economy. She captures the frustration of poverty, the lack of financial independence and joblessness. There are many insights to the world these women inhabit, but little into their own minds.

The story “Charts” is about two sisters, both adopted, who once loved each other dearly, but now hardly recognize one another. The sister telling the story is filled with dread and anxiety, not only because she is an outsider, but because she has no hope for being a part of anything – not even her sister’s wedding.

Like many of the stories, it is well written, but barely scratches the surface of the girl’s pain and suffering. As a reader, I’m not necessarily looking for a psychological profile, but I do want to empathize and get more insight into a character’s worldview and mind-set. Miller gets bogged down in daily minutia, which can be entertaining and humorous, but fails to deliver much emotional impact or character depth.

And it’s not the men who are the problem. In fact, none of the men in this book are bad people or awful to women. It’s the women who can’t get it right.

Rather than working on living happy and fulfilled lives as free and independent thinking women, there is a sense that the women in these stories are completely dependent on men to make them happy – even when they don’t.