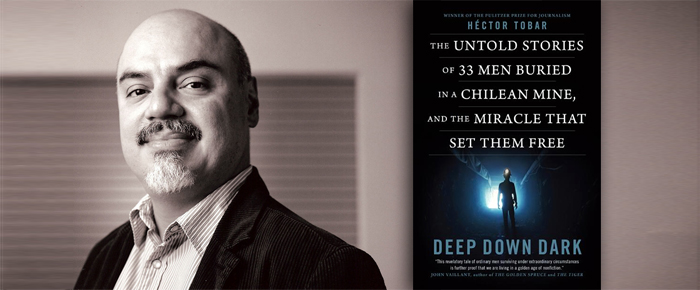

By Heidi Simmons

—–

Deep Down Dark

by Héctor Tobar

Non Fiction

—–

One of the greatest human fears is being buried alive. Add to that the terrifying concern that you may be unimportant – that your life doesn’t matter since extracting you is too difficult. Then, throw in the horror of losing your humanity, wasting away as you wait months hoping to be rescued. That’s living in Hell.

In Héctor Tobar’s Deep Down Dark: The Untold Stories of 33 Men Buried in a Chilean Mine, and the Miracle That Set Them Free (Farrar Straus Giroux, 310 pages), miners struggle to stay alive under 770,000 tons of solid rock 2,200 feet below the surface of the earth for 69 days!

August 5, 2010. Thirty-three miners go to work at the San José, a privately owned mine in Chile, 40 minutes from the small mining town of Copiapó. The mine produces copper sulfate from which copper and gold are extracted. San José has 720 levels and is over 100 years old.

Several men had noticed the widening crack in an upper level ramp. Those down below heard and felt the mountain rumble for days. But the men know the risks of being miners — that’s why they get the big bucks of $180 a day. On August 5, there are double the men working to make up hours and do overtime.

When the mountain gives way and the cave-in begins, one man’s teeth are knocked out by a falling rock, but amazingly no one is seriously injured or killed! After the dust settles, the men gather in a classroom-size safe area called the Refuge. It’s here they will meet to eat what little food they have and do they’re best to hold on to their sanity.

With a double crew and a mine that was not kept up to emergency standards, there is not enough food. The men will subsist on 300 calories a day and then 100 calories every other day before contact with the world is made.

They are buried with trucks, tractors and heavy lifters for moving tons of rock. The vehicles cannot dig them out, but they provide fuel and battery power to their failing lights. Fortunately, there is ample water — but it is tainted with motor oil. They drink it.

The temperature is over 100 degrees and humidity is 98 percent. Two types of men emerge: “doers,” those who want to find a way out, and “waiters,” those who are resigned to their fate. Personalities become defined as men break or rise. They are all starving.

After 17 days, on the edge of death, a 4.5-inch whole breaks through and they are eventually sent down food. But it will take another 52 days before they are rescued. The mountain continues to collapse and their spirit dwindles.

On the surface of the earth, there is another drama unfolding. Families are gathering. Wives, mothers and mistresses clash with each other and government officials over the search and rescue of the men they love. They will not be ignored just because they are poor laborers “with timeworn clothes and callused hands.”

The media is present and the event goes global. Countries around the world offer help and equipment. From day one, the families make Camp Hope outside the gates of the mine. A sister of one of the miners will become the Mayor and a liaison with the President, engineers and recue workers. She stays awake and checks every time she hears a drill stop in its search. She and others never give up hope the men will be rescued.

When the men are first discovered alive, bells ring across the nation. Like Kennedy’s assassination, Chileans remember where they were when the heard the news.

The Chilean government assembled experts that included psychologists, doctors and engineers. The men drilling the escape routes are equally invested in getting the men out. They work around the clock. They have three plans going simultaneously, although there is no guarantee of success.

After another seven weeks, the men are pulled up in a capsule ride that takes seventeen minutes — a time-consuming, nerve-wracking journey that keeps some men an extra day underground.

The thirty-three survivors are considered heroes and showered with gifts and money. But none of the rewards help with their Post Traumatic Stress. They will never be the same and the event continues to haunt their lives.

A Chilean judge found the San José mine owners not criminally culpable in the collapse.

Author Tobar gives the reader a first person, as well as a first time look at this fantastic story of survival. Before the men emerged, they made a pact to not share the first 17 days of their story with anybody. A decision that may have caused prolonged suffering and slowed the healing process.

So profound, intense and intimate, the story the thirty-three shared belonged to all of them. Knowing the incredible worldwide interest in their individual and collective stories, they decided to act as one in the telling of the cataclysmic event and the nightmare it unleashed. Any book, or movie deal monies, would be split equally. In fact, they formed a corporation just weeks after surfacing.

As an intellectual, Tobar sees the big picture and brings to the narrative the socio-political complications and ramification of the minor’s rescue on their core humanity. A Pulitzer Prize winning journalist, he is meticulous about describing the conditions of their life above and under ground. And as an acclaimed novelist, Tobar reveals the pathos and heartbreak of the devastating event and the miner’s painful road to redemption and recovery. Tobar not only does justice to their stories, but he delivers it with beauty, dignity and grace.

Deep Dark Down is a life-affirming tale of resilience, strength and frailty. When human beings act with determination, kindness and unconditional love, they can literally move mountains and escape the confines of Hell.