By Heidi Simmons

—–

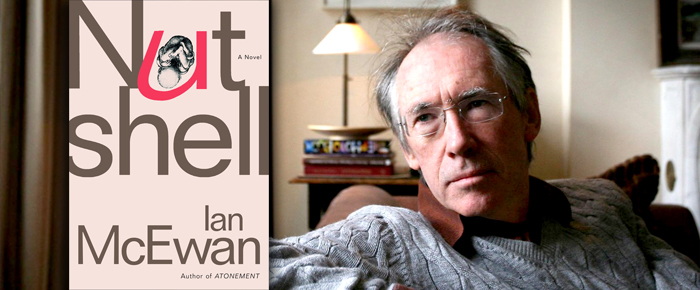

Nutshell

by Ian McEwan

Fiction

—–

Human procreation is a miracle. When it comes to awareness, there is still so much we don’t know about fetal brain cognition. How much do the unborn know? What emotions do they feel? Can they comprehend their reality in utero?

In Ian McEwan’s latest novel, Nutshell (Nan A. Talese, 208 pages) an unborn child is held in natal suspense as his parents plan for his arrival.

The narrator in this story is the fetus itself. Nearly nine months old, he has turned and dropped into position for birth. Although he is ready and preparing to meet his mom and dad, there is a problem. Mom and dad are living separately, and his mom wants to kill his dad.

The fetus’ mother, Trudy, is 28 years old and she has lost all interest in her poet and professor husband, John. She is living in her husband’s family London flat which is decrepit and a filthy mess. Trudy is having regular sex with Claude, John’s businessman and bore of a brother.

Eavesdropping during his mother’s most intimate moments, the fetus learns that Claude has come up with a plan to kill John by poisoning him with ethylene glycol, a very painful, but quick death that is difficult to prove.

Unfortunately for the baby, Trudy plans on also getting rid of her unborn baby as soon as possible. Helpless to do anything and with his mother drinking too much wine, he cannot think straight. The fetus can only listen in fearful apprehension as events unfold.

Oh, the pleasure of reading a story with an unreliable narrator! This is such a strange conceit, but it is a hard book to put down. Somewhat Shakespearian in plot, the unborn, precocious child cannot fully grasp the world outside.

At one point he uses his “fetal power” to transport himself to a place where his father and uncle are negotiating the future. The reader is informed by the fetus that his father did not take the bribe (to leave) but acted nobly wanting only to be reunited with his wife and baby.

However, when Claude comes back from the negotiations and shares the event with Trudy, it is not at all as the unborn child had imagined. In fact, it is the opposite. What the child believes about his father is rarely true and is often contradicted by his mother and uncle as he listens to their discussions beyond the womb.

This gives the reader pause, because we cannot be certain that the child is totally incorrect, and at the same it is easy to believe that Claude is a liar and not telling Trudy the whole truth.

These moments of ambiguity are delicious to read and keep the story at a provocative level of suspense. What is really going on?

Author McEwan writes beautifully and he captures a voice in the fetus that makes sense and rings true, that is, if indeed, the fetus had a mental awareness and intelligent insight of his exterior world.

The unborn child struggles to understand why his mother and father hate each other. The adult lives are complicated, confusing and frankly ridiculous. The fetus wants to love his mom and his dad. He wants a future, but sadly his future unclear. He is troubled by their lack of concern for him. He is not a part of his parents’ conversation. It is not even clear if the baby will likely be born at all.

I especially like that the baby believes, and tries, to use powers he believes he possesses because he is a fetus. This is remarkable in and of itself, because shouldn’t a fetus have magical abilities?

Nutshell is a fresh and surprising read proving again that the unreliable narrator makes for a very entertaining and engaging way to tell a story.