By Eleni P. Austin

Scott Miller was born in 1960 and grew up in Sacramento. In fact his family originally settled there during the California gold rush of the 1850s. His parents had an eclectic record collection that included Broadway show-tunes and a cross-section of Folk music. By the time he was school-age he was obsessed with the Beatles and the Monkees.

At age nine he began taking guitar lessons and by the time he was 11 he had formed his first group. Not really realizing you probably shouldn’t name your band after an existing band, he called his four-piece the Monkees. Apparently, he assumed Mike Nesmith role. No evidence exists that he sported a wool cap.

Scott seriously pursued music during his junior high years. By high school he was fronting bands like Lobster Quadrille, Mantis and Resistance. When he began attending college at UC Davis his latest aggregate was known as Alternate Learning. A going concern from 1977 to 1982, they recorded a 7” EP in 1979 and released a full-length LP, Painted Windows, on Rational Records in 1981.

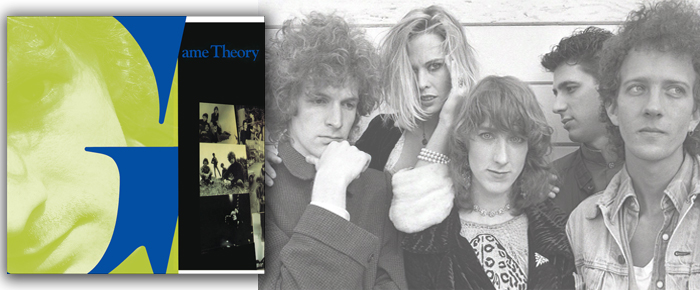

The following year he formed his longest lasting band, Game Theory. Named after the mathematics strategy, the original line-up included Scott as lead vocalist and guitarist, Nancy Becker on keyboards, Fred Juhos on bass and vocals and Michael Irwin on drums. Operating on a shoe-string budget, they recorded their 1982 debut, Blaze Of Glory, for Rational Records. Lacking the funds to both press and package the album a thousand copies were originally released in white plastic trash bags with photo-copied cover art glued to the bags.

Game Theory’s sound was a pithy synthesis of Power Pop and lush Psychedelia. Instrumentation and arrangements were dense and intricate, the lyrics verbose. They immediately struck up a loose affiliation with L.A.’s Paisley Underground bands, (Three O’Clock, Dream Syndicate, Rain Parade and The Bangles). In fact, when Game Theory released a pair of EPs in 1983, Pointed Accounts Of People You Know and Distortion, Three O’Clock front-man Michael Quercio produced the latter.

By this time, Dave Gill replaced Michael Irwin behind the drum kit. (Personnel changes would plague the band, Scott Miller remaining the only constant presence throughout the years). Game Theory signed with Enigma Records, and for their second full-length, Real Nighttime, the band hooked up with protean producer Mitch Easter.

A native of North Carolina, Easter was part of the seminal ‘70s Power Pop band the Sneakers before opening Drive-In Recording Studio in Winston-Salem. Along with fronting his own band Let’s Active, he began to make a name for himself as a producer on R.E.M.’s debut EP and their first two long-players.

Mitch was a perfect foil for Game Theory, providing Scott Miller with a broad sonic canvas. The result was something akin to an Indie-Pop Pet Sounds. Scott’s affection for Big Star was also made explicit with the band’s cover of Alex Chilton’s “You Can’t Have Me.”

Mitch Easter remained Game Theory’s producer on the band’s next three records. From1986’s Big Shot Chronicles, he continued with 1987’s double LP magnum opus, Lolita Nation and 1988’s Two Steps From The Middle Ages. Each effort was met with rapturous and universal critical acclaim.

Mitch Easter remained Game Theory’s producer on the band’s next three records. From1986’s Big Shot Chronicles, he continued with 1987’s double LP magnum opus, Lolita Nation and 1988’s Two Steps From The Middle Ages. Each effort was met with rapturous and universal critical acclaim.

The band had accrued a small but devoted following that included contemporaries like Aimee Mann (who was then the front-woman for ‘til Tuesday), and Stephin Merritt, (visionary behind bands like Magnetic Fields, The 6ths, The Gothic Archies and Future Bible Heroes). They also made an impression on up-and-comers like the Posies, Ted Leo and Spoon front-man Britt Daniel. Unfortunately, commercial success still eluded their grasp. After myriad line-up changes that included Jozef Becker, Gil Ray, Shelley LaFrenaire, Suzi Ziegler, Donette Thayer and Guilliaume Gaasaun, Scott pulled the plug in 1990.

Ironically, he reconvened some of the same players for his new project, the Loud Family. The band was named after television’s first reality series, “American Family.” A groundbreaking early ‘70s documentary that saw an all-American family practically implode before the cameras. (It’s also where eldest son, Lance, came out as gay, literally in front of America).

Between 1991 and 2006 the Loud Family released seven albums and one EP. Early in the new millennium Scott and acolyte Aimee Mann recorded a number of tracks together, but those have yet to see the light of day.

In 2010, Scott wrote a well-received critical history of Rock & Roll entitled Music: What Happened? He had also reactivated the Game Theory moniker and was in the process of writing new music for a new album when, tragically, he took his own life in April, 2013. He left behind a wife and two daughters.

For years, the entire Game Theory catalog has been out of print, but thanks to the fine folks at Omnivore Records, that wrong is finally being rectified. Omnivore, has quickly eclipsed Rhino Records as the go-to label for comprehensive re-issues of forgotten treasures.

To paraphrase the “Sound Of Music,” they started at the beginning, a very fine place to start. Going all the way back to Game Theory’s genesis in 2014 they released the band’s 1982 debut, Blaze Of Glory and included 15 bonus tracks. Dead Center, a compilation of their two EPs, followed less than six months later.

The Real Nighttime re-issue appeared in March 2015 a year later the label jumped the chronological order releasing the double album Lolita Nation. Now they take a leap back in the space-time continuum to properly deliver the 1986 record The Big Shot Chronicles.

The album opens with the pulsating “Here It Is Tomorrow.” A pummeling backbeat, fuzz-tastic guitars, jet-set keys and thrumming bass provide ballast for wildly loquacious (but crazily cryptic) lyrics like “Quick judger, longtime begrudger dialed in to the pyramid structure/Efficacious B-follows-A-cious, something you can shove in their faces, holding out for maximum missed time, the stereotype was right this time.”

Re-visiting this album 30 years on, it’s frankly shocking that this band wasn’t more popular. Their music builds on the sharp Beatles/Monkees paradigm and adds the more wistful sounds of Brian Wilson and Big Star. The first single, “Erica’s Word,” is powered by an infectious handclap rhythm, stuttery acoustic riffs and a kaleidoscopic electric guitar solo that spirals and exhales. All the while Scott addresses an ex who is “taking me clear and leaving me blurred, singing the praise and playing the blues/Pulling the rug out from under my shoes.”

Several tracks here are ridiculously non-stop catchy. The dizzying “Make Any Vows” is fueled Gil Ray’s breakneck backbeat. Rubbery bass and spacey keys quietly underscore ricochet guitars that jangle one second and squall the next. The lyrics offer this tart metaphor for a rickety romantic relationship; “Latticework without foundation holds as long as we agree/Question and you’ll hear it buckle, all on your own suddenly.”

Tilt-A-Whirl guitars shimmer and shake over sparkly keys and a workman-like rhythm on “I’ve Tried Subtlety.” The lyrics make veiled references to a school prom, political expediency and an attempted Grand Theft Auto. If the listener is left scratching their heads, Scott promises to do better; “I’ve tried subtlety before, but I will not anymore.”

The action slows for four tracks. “Book Of Millionaires” is awash in phased keys that almost tilt the song in a Prog-Rock direction. Fleet acoustic fretwork threads through the instrumental tapestry along with piquant electric riffs. The lyrics are a caustic commentary on television that pre-sages the Kardashian-ization of the airwaves; “Who’s this they’re letting get on TV, he’s new and he’s great and it’s just not me.”

The twangy guitar, languid melody and relaxed back-beat of “Too Closely” belie lyrics that straddle the line between romantic supplication and passive-aggressive stalker-ism. “If you were here I would wait, wait all day right here/If no one were watching girl, I guess I’d wait all year.” Yikes.

“Where You Going Northern,” pairs rippling acoustic licks with bent electric notes. As the tempo gathers speed, Scott bemoans the loss of a kindred spirit; “Cause you see the world just as I do, and we do the things that I say to/But one day you’ll do what you want to.”

“Regenisraen” is a Folky, Elizabethan roundelay. The instrumentation is pared down to trickling acoustic arpeggios and pastoral keys. They blur together, accenting the madrigal bliss of Scott, Shelley and Suzi’s vocal blend. The title is a bit of Scott jabberwocky that co-opts the words regenerate and rain.

The two best tracks, “Crash Into June” and “Never Mind,” kick the album into interstellar overdrive. On the former, flickering guitar riffs pogo in and out of the melody, then collide with stabby, New Wave synth fills, roiling bass and a caffeinated rhythm. The lyrics kind of come to terms with intense nostalgia for the recent past; “And if I answer to a different hunger from the one I had when I was younger/Please remember that it’s still just me inside.”

The latter is anchored by fuzzy, distorto guitar, furrowed bass lines, a see-saw rhythm and playful vocals. The shambolic melody is a cosmic cousin to “A Legal Matter,” the Who’s early treatise on domestic ennui. The quick, scattershot guitar solo is drenched in feedback.

The album closes with “Like A Girl Jesus.” Tender and tentative, the song feels like an sideways homage to the Velvet Underground as well as the gossamer delicacy of Chris Bell’s Big Star songs; a quiet and contemplative end to a classic record.

As with their previous re-issues, the kids at Omnivore don’t disappoint with the bonus content. 14 extra songs make up a plethora of essential ephemera. They include some trenchant covers; Vince Guaraldi’s “Linus And Lucy,” Todd Rundgren’s “Couldn’t I Just Tell You,” Roxy Music’s “Remake/Remodel” and Big Star’s “Jesus Christ.” Randomly there’s a version of “Seattle,” the theme from the TV series “Here Comes The Brides” and a live take of the Velvet Underground’s “Sweet Jane.”

There’s also rough mix versions of “Erica’s Word” and “Like A Girl Jesus,” plus a two-track demo of “The Only Lesson Learned.” Live offerings of Game Theory songs include “Make Any Vows” and “Friend Of The Family.” Rounding out the bonus set is a rehearsal of “If And When It All Falls Apart” and a particularly affecting acoustic rendering of “Come Home With Me.”

The Big Shot Chronicles, as well as the rest of Game Theory’s oeuvre, is ripe for rediscovery. Thankfully, it’s all been lovingly curated by Omnivore. Sadly, Scott Miller was never fully appreciated in his own lifetime. But revisiting these classics makes it clear that he left a musical legacy that is both beautiful and bittersweet.