By Eleni P. Austin

There’s a melancholy catch in Kim Richey’s voice -even when she’s singing a happy song, that pulls you in and holds you close. For nearly three decades, she has been one of Nashville’s best kept secrets. The musical cognoscenti recognized her gifts rather quickly. Her prodigious talent was on full display with her 1995 debut. But to the world at large, she’s probably better known for having written #1 hits for folks like Trisha Yearwood and Radney Foster.

The Ohio native spent her formative years haunting her Aunt’s record shop. She had free reign over the singles bin, allowing her access to music from artists like The Lovin’ Spoonful and Janis Joplin. She received her first guitar at age 12, by high school, she had already cycled through a series of nascent bands.

Following college, she satisfied her wanderlust by traveling the world. She spent the balance of her ‘20s in Colorado, Europe, South America, Boston and Washington state. During that era, she woodshedded in a variety of bands, earning her keep as a cook, waitress and animal rights advocate.

She put down roots in Nashville in 1988. By this time, she looked to two musical avatars: Joni Mitchell, the doyenne of Laurel Canyon and shapeshifting singer-songwriter who invented her own guitar tunings and followed her muse, sometimes to the consternation of critics and fans. Steve Earle, her other big influence. The brash and unfiltered Texas troubadour had recently been hailed as Country Music’s answer to Bruce Springsteen. But that didn’t stop him from railing against Nashville’s rigid traditions.

For all her precocity, Kim was a bit of a late-bloomer. At age 37, she inked her first deal with the Mercury Nashville label. Her self-titled debut arrived in 1995, followed in quick succession by Bittersweet in 1997 and Glimmer in 1999. Critical acclaim was unanimous, but commercial success proved elusive.

Luckily, peers like Mary Chapin Carpenter and Shawn Colvin took notice, as did the industry. She chose not to compete with glamor girls like Faith Hill, Shania Twain or Martina McBride. But beneath her tomboyish demeanor lurked a crackling sense of songcraft. Brooks & Dunn, Radney, Trisha, Mary Chapin, Patty Loveless and the (Dixie) Chicks all rode Kim’s songs to the top of the Country charts.

In 2002, former Mercury-Nashville label president Luke Lewis signed her to his new boutique imprint, Lost Highway Records. Kim’s signature sound, a sharp distillation of Folk, Rock, Country and Pop, seemed more at home alongside like-minded labelmates like David Baerwald, Elvis Costello, Shelby Lynne, The Jayhawks, Lyle Lovett, Willie Nelson and Lucinda Williams.

The label change also altered her creative process. Her 2002 album, Rise, was recorded in California rather than Nashville. Handling production chores was music industry veteran Bill Bottrell (best known for producing Sheryl Crow’s monster debut, Tuesday Night Music Club). Stepping a little outside her comfort zone paid off. Escaping the staid confines of Nashville, she wound up introducing her music to a whole new fan base of NPR listenin,’ Starbucks drinkin’ aesthetes.

Since then, Kim has made a habit of subverting expectations. Her 2007 album, Chinese Boxes, produced by Giles Martin, son of famed Beatles producer, George Martin, was adventurous and under-appreciated. In 2010, she took another left turn with Wreck Your Wheels. While Chinese… was bespoke and ornate, Wreck had a loose, lived-in feel.

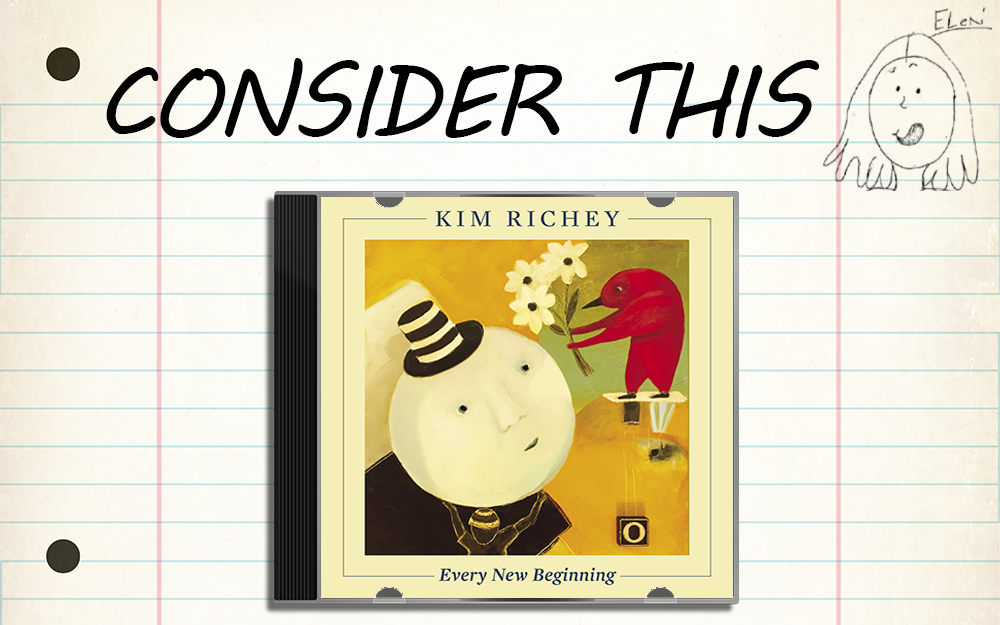

She returned in 2013 with Thorn In My Heart, a bare-bones affair, it charted a journey from heartache to spiritual redemption, it was a bare-bones affair. Edgeland arrived five years later then in2020 she released A Long Way Back: The Songs Of Glimmer, an album that revisited and recalibrated her 1999 album, Glimmer. Now she’s returned with her 10th long-player, Every New Beginning.

The album’s opening tracks form a diptych of sorts that serve as the earliest chapters of Kim’s origin story. “Chapel Avenue” weds sun-dappled acoustic guitars, thrumming bass, hushed pump organ and meandering piano to a barely-there beat. Lyrics take a trip down memory lane: “Skateboards and lemonade stands, 4rh of July bands, creature feature matinees, high dive-I double dare you, hormones enough to scare you, day-dreaming summertime away….Sissy bars, banana seats, popping wheelies down our street, time flies, sometimes at the speed of light.” Revisiting childhood haunts and her earliest touchstones, she acknowledges: “All the gold of yesterday is a debt I can’t repay, I owe it all to you, Chapel Avenue.”

“Goodbye Ohio” extends the journey, as tangled guitars and plucky mandola wash over thready B-3 organ, plaintive piano and wily bass lines. The arrangement gathers speed as a stalled romance provides the impetus for a change of scene: “Don’t let the fire die down, don’t let the light fade in your eyes, to think we’ve lost the spark is enough to break my heart, goodbye Ohio, goodbye to all I know.” Guitars slash across swirly B-3 on the break, it feels as though the die has been cast.

A few tracks here find Kim coloring outside the lines. Take “Come Back To Me,” a bit of a back porch ramble. The instrumentation weaves an aural tapestry of swoony strings, bucolic banjo, prickly mandolin, sparkly piano, acoustic and resolectric guitars and a wheezy pump organ. There’s a heartsick ache to Kim’s voice as she searches the heavens for a long-gone love: “And here between the earth and sky I wait and wonder where you are tonight, and if I look up just in time to see a star fall down, then you just might come back to me, come back to me.”

“Floating On The Surface” could sandwich nicely between Tom Petty and The Motels on any early ‘80s radio station. Flinty guitars wrap around subterranean bass lines, wayward keys and percolating percussion. Fluid lyrics advocate for skimming the surface rather than plumbing the depths beneath a shallow relationship: “Floating on the surface, never making waves, at the bottom of the sea, there’s too much mystery, and so you and me, we keep floating on the surface, we keep floating on the surface/We don’t worry cause the water’s so peaceful, we hide behind the colors nailed to the mast, underneath a sky as blue as the ocean, drift on the current and we never look back.”

Co-written with Indie Roots-Rocker-wunderkind, Aaron Lee Tasjan, “Joy Rider” exhibits a spiky exuberance. Plunky piano notes partner with scratchy guitars and a jittery beat. Sly lyrics celebrate the return of a rebel without a cause: “He’s got a midnight wheelie, it’s the talk of the neighborhood, he’s screaming up and down the side streets, cause it makes him feel so good.” On the break, ricocheting guitars double-down on the joie de vivre.

The best songs here are “The World Is Flat” and “A Way Around.” The former is a wistful waltz powered by pointillist piano, moody Mellotron, woozy Wurlitzer, chunky guitars and a laid-back beat. Lyrics attempt to navigate the rocky shoals of of a fractured romance: “Let’s take this affair to it’s logical place, we can’t bare to fix it, so we’ll throw it away/It’s hard to be kind when you’re caught in the middle, the best we can do is try and be civil, we twist and turn but, we can’t solve the riddle, we’ve come to the edge of the map, only to find that the world is flat.” The melodic melancholy echoes antecedents like Carly Simon’s “That’s The Way I Always Thought It Should Be” and Aimee Mann’s “4th Of July,” as a keening flugel horn solo on the break offers a soupcon of regret.

Guitars shimmer and simmer across tensile bass and a knockabout beat, as Mellotron and piano color that margins of the melody on “A Way Around.” Lyrics limn the familiar feeling when no matter how hard you try, nothing goes right: “Drop the needle on your favorite sad song, you’re not the only one whoever got it all wrong, just another lonely one/You’ve been looking for a way around, water keeps rising ‘til you think you’re going to drown, can’t seem to get to higher ground, it’s one step forward and two steps back, I know how you’re feeling when you’re feeling like that.” Cascading guitars and spiraling harmonies usher the track to a close.

Aside from Aaron Lee, Kim collaborated with a plethora of fine folks (Don Henry, John Hadley, Jaime O’Hara, Brian Wright, Roger Alan Nichols, Peter-John Vettese, Ashley Campbell and Mondo Saenz), but she goes it alone on a couple of tracks. On “Take The Cake” stinging electric licks lattice, knotty acoustic riffs, willowy cello and see-sawing violin and viola. Lyrics like “Peter Pan’s got nothing on you, as far as I can tell, but you might find as the years go by, it’s a harder sell” take an incorrigible Ex to task.

Meanwhile, the piano-driven “Feel This Way,” is equal parts torch and twang. Lyrics acknowledge that sometimes no matter how we try, we can’t outrun grief: “The Sun can’t shine when the rain comes down, knowing it will come back doesn’t bring it back around, I would, if I could push a button, throw a switch, and in a heartbeat, I’d be on the other side of this.” Stacked harmonies on the chorus add a bit of Gospel heft to the proceedings, that’s nearly undone by the scabrous guitar solo on the break.

The record closes with “Moment In The Sun.” Willowy piano notes are matched by lithe acoustic guitar, spidery bass feathery Mellotron and a thwoking beat. Empathetic lyrics offer a bit of a cosmic exhale: “This is your moment in the sun, far to bright to see the end, until it’s over, said and done, your moment in the sun. A lanky flugel horn solo uncoils, underscoring that fleeting feeling that for once, everything is right with the world.

Long ago, Kim Richey earned accolades from contemporaries like Mary Chapin, Shawn Colvin and indigo girls. More recently, younger artists like Americana superstar Brandi Carlile and rising stars like Brandy Clark and Allison Russell have been singing her praises. Her music truly transcends generations. Every New Beginning is by turns heartfelt, nostalgic and sagacious. It extends the winning streak that began with Kim’s debut.