By Aaron Ramson

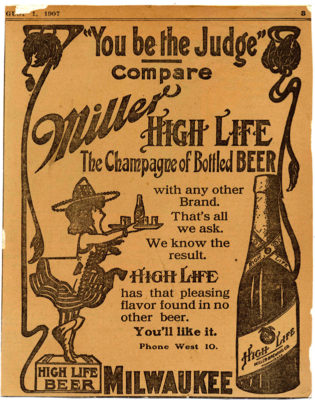

You know, for a product that is found almost exclusively in gas stations and dilapidated liquor stores, Miller High Life has some nerve calling itself the champagne of beers. The $7.49 per 12-pack price tag doesn’t exactly scream bourgeoisie (pronounced bo͝orZHwäˈ and is where we get the term “bougie” from), and one can only speculate that the champagne comparison in question is more Barefoot than Cristal. But have you ever wondered where Miller got that marketing idea from? No? Me neither, yet here we are.

In the late-1800’s, beer was almost exclusively draught (tapped from a keg and pumped using gas or air pressure) and enjoyed in saloons. If you really wanted to enjoy your beer outside of the pub, you’d have your bartender fill the small, galvanized pail that you brought him, and cover it with a lid. As you walked home, the CO2 would escape from under the lid as the beer sloshed, creating a growling sound, and that is where the name for beer growlers came from. Bottled beer was a rarity, namely because the beer had a propensity to undergo secondary fermentation in the bottle and explode like a grenade. This all changed in the 1870’s, when French scientist Louis Pasteur popularized the process of using heat to kill yeast and bacteria in bottled beer. This process became known as pasteurization, and it made beer bottles shelf stable for the first time. With William Painter’s invention of the bottle cap in 1892, American breweries now had the means to sell single pints of beer in glass bottles with a pry-off lid, paving the success for brands like Budweiser, Coors, and Miller.

In the late-1800’s, beer was almost exclusively draught (tapped from a keg and pumped using gas or air pressure) and enjoyed in saloons. If you really wanted to enjoy your beer outside of the pub, you’d have your bartender fill the small, galvanized pail that you brought him, and cover it with a lid. As you walked home, the CO2 would escape from under the lid as the beer sloshed, creating a growling sound, and that is where the name for beer growlers came from. Bottled beer was a rarity, namely because the beer had a propensity to undergo secondary fermentation in the bottle and explode like a grenade. This all changed in the 1870’s, when French scientist Louis Pasteur popularized the process of using heat to kill yeast and bacteria in bottled beer. This process became known as pasteurization, and it made beer bottles shelf stable for the first time. With William Painter’s invention of the bottle cap in 1892, American breweries now had the means to sell single pints of beer in glass bottles with a pry-off lid, paving the success for brands like Budweiser, Coors, and Miller.

When the Miller Brewing Co started bottling in 1903, they decided that their marketing point would be to show off the color and clarity of their beer. Boasting a product with higher carbonation than was found in any draught beer, Miller began using the infamous champagne tagline to highlight similarities of their beer to bright, sparkling wine, creating an air of class and luxury around their product. Calling it “High Life” beer cemented Miller’s claim to the bourgeoisie, and it had a reputation as one of the pricier beers on the market. Can you imagine?

The shape of Miller High Life’s bottle has evolved over the years, but the sloped shoulders and clear glass have remained consistent with the brand. Many craft beer fans look at prohibition as the catalyst that changed and watered down the production of American beer, but it was in fact WWII. Almost every resource became rationed and scare during the wartime effort, and barley was no exception. Needed to bake enough bread to feed massive armies in a pre-GMO period, brewers no longer had unprecedented access to the grain from which their beers were made. Rice, corn, and other fermentables were incorporated in the recipes of every big brewery, altering the flavor and giving a much less robust taste. The unexpected upside for breweries was a lighter colored beer, which they liked, and a cheaper product to make, which they liked even more. When the war ended, and barley was no longer a scarce material, almost every major brewery continued with the corn and rice heavy recipes they’d created, and Miller was no exception.

In 2019, Miller High Life remains a favorite beer amongst college kids and urban hipsters alike who enjoy the kitsch and ironic appeal of a beer as uncool as high Life. Miller is fully aware of the zeitgeist we live in and makes no apologies for its beer. In a move of total transparency, Miller lists the ingredients for high Life on its website as “Water, Barley Malt, Corn Syrup (Maltose), Yeast, Hop Extract.” A blurb in front of the ingredient list informs us that the beer is made with “light stable galena hops from the Pacific Northwest,” which is Miller’s reassurance to us that their clear bottled beer resists being skunked thanks to the magical powers of Galena hop extract. Miller smartly then lists the many awards won by High Life, including a Silver medal at the 2016 World Beer Cup.

I’m not going to review High Life here, if you’re familiar with it then you know that the flavor is the epitome of standard, mass-produced lager. I prefer Coors Banquet to High Life, but I understand why this beer is enjoyable to so many. It’s blandly pleasant, with a grainy and almost cider-like dryness that’s not offset by any hop bitterness or character whatsoever. Kinda like champagne.