By Eleni P. Austin

Back in the late ‘70s/early ‘80s, Los Angeles was something of a musical melting pot. There was a thriving Punk Rock contingent, headed by X, The Germs and The Weirdos, Skinny-tie bands like The Knack, The Plimsouls and 20/20, mined a Power Pop sound that originated the ‘60s. The Bangs, The Dream Syndicate, Rain Parade and The Three O’ Clock also took inspiration from music that came of age in the swinging ‘60s: Psychedelia and Garage Rock. They co-existed peacefully with the Punk/Blues/Rockabilly of Gun Club, the trashy Rock/R&B Mash-up of Top Jimmy & The Rhythm Pigs and the Rootsier sounds of The Blasters and Los Lobos.

It was around this time that Kentucky native Sid Griffin arrived in L.A. He had always evinced a strong affinity for legendary L.A. bands like The Byrds, Buffalo Springfield and The Flying Burrito Brothers, who, along with former teen idol Rick Nelson and Monkees’ guitarist Mike Nesmith had synthesized Country, Folk and Rock into an irresistible musical elixir. After playing in a couple of bands, he struck out on his own.

Connecting with Virginia transplant, and Country music aficionado Stephen McCarthy, British Des Brewer and L.A. local, Greg Sowders, their sound began taking shape. As The Long Ryders, they wore their influences on the sleeves of their fringed, suede jackets. The four-piece hit the ground running, playing all the local clubs and recording their debut EP, 10-5-60 in 1983. Their sound was a sharp amalgam of Country, Folk and Rock.

Around the time they signed with Lisa Fancher’s local indie label, Frontier, Des bowed out and Indiana native Tom Stevens took over bass duties. They enlisted former Flying Burrito Brothers producer Henry Lewy to hem their first long-player, Native Sons. Critical acclaim was unanimous, and the album was hailed a “modern classic.” Big labels took notice and the band signed with Island Records. Their next two records, 1985’s State Of Our Union and 1987’s Two-Fisted Tales, cemented their position in L.A.’s shifting musical soundscape. While their melodies continued to reflect beloved antecedents, their lyrics were aligned with local contemporaries like X, The Blasters and Los Lobos. Each record explored the ever-widening chasm between the haves and have-nots in the era of trickle-down Reaganomics. Even though they were tapped to open a string of dates with newly-minted superstars (and label-mates), U2, commercial success continued to elude the band. Frustrated, Stephen and Tom left the band. A little while later, Sid and Greg quietly called it quits. Of course, it was The Long Ryders (along with The Rave-Up’s, Rank & File and Jason & The Scorchers) lit the fuse that was later labeled alt.country or Americana. By the ‘90s, bands like Uncle Tupelo (which broke up and became Son Volt and Wilco), The Jayhawks and I See Hawks In L.A. picked up that torch. The band has reunited sporadically throughout the years in 2004, 2009 and 2014. A few years later, the guys received an offer they couldn’t refuse from Larry Chatman. Larry began his career as part of The Long Ryders’ road crew. These days, he works for iconic Hip-Hop producer, Dr. Dre.

Larry was able to secure a week’s worth of recording time at Dr. Dre’s state-of-the-art studio gratis, as a thank you to the band that gave him his start. The guys jumped at the chance to make new music. They recruited producer Ed Stasium, and their long-awaited fourth album, Psychedelic Country Soul, arrived in 2019. Rave reviews and respectable sales were sweet vindication for a band that had nurtured a sound decades before, It felt like they had come full circle.

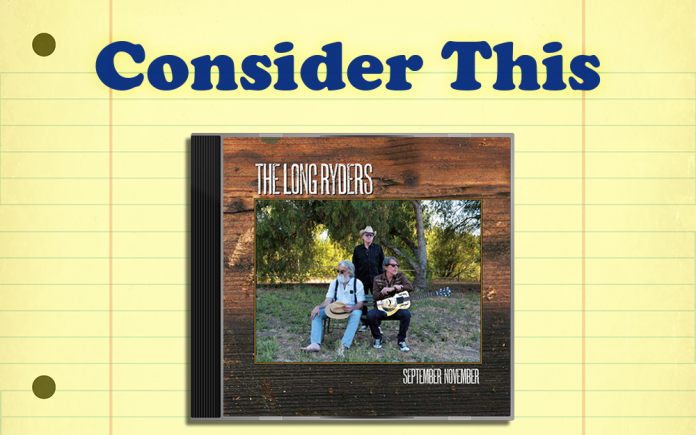

At the start of 2021, Sid, Greg and Stephen were dealt a bitter blow when Tom Stevens suddenly died from undisclosed causes at age 64. Despite their personal devastation, the trio opted to soldier on. In the summer of 2022, they hunkered down at Kozy Tone Ranch in Poway. The result is their fifth long-player, September November.

The album kicks into gear with the driving title track, “September November Sometime.” Swooping violin, jangly guitar, and thrumming bass are tethered to a galloping gait. Playful lyrics update Smokey and The Miracles’ old rallying cry; “Calling out across the world, are you ready for a brand new tweet?” The band originally took their moniker (and tweaked it in a Byrdsian fashion) from Walter Hill’s scabrous Western, The Long Riders, so it feels wholly apropos that this song finds the band in full desperado mode. As manic violin notes dart and pivot through the mix, Sid, Stephen and Greg unspool a different kind of outlaw yarn; “September November sometime, the cracked bells so softly wind chime, the sound of guns on one hard climb, my band of fools is ridin’ against time, ridin’ against a Sea Of Holes while wearing black to fit my role, the task I chose, the life I lead, before a judge I’d never plead, never plead, never would concede.”

Following that raucous opening salvo, the band dials back the primal Punk attack, locking into a more peaceful, easy, feeling (without that bitter, Eagles aftertaste). “Hands Of Fate” is powered by meandering mandolin, beatific bouzouki, sylvan keys, chiming guitars, sturdy bass and a brushed beat. Something of a restless farewell, soulfully succinct lyrics bid adieu to this corporeal existence; “Now I sing this solemn song, sing it low, when I’m gone, the hand of fate it took me down this time.”

Then there’s the autumnal grace of “Seasons Change.” This mid-tempo groover weds twangy guitars, brittle bass lines and shadowy keys to a tilt-a-whirl beat. There’s a tender ache to lyrics that chart the inevitable passage of time, and the folks we lose along the way; “Have you seen the twilight turning today, the summer sun is slowly fading away, but I hope you know, any place you go, your love will always shine like an afterglow so we’ll meet again when the road comes back around, I have a memory and it’s triggered I have found, when leaves are falling down, seasons change, but my love will stick around.” Gritty guitars hug the melody’s aural switchbacks. Scorching riffs unleash on the break, leavening the doleful sentiments contained herein.

Cawing Ravens launch “Flying Down” before drifting into elegiac, Jimmy Webb territory. Baritone guitars lattice burnished acoustic licks, swoony strings, keening pedal steel, wily bass lines and a stutter-y beat. At first glance, aerial lyrics offer a bird’s eye view; “I am high, high, high, over my home, over and done with for a while, I am gone, gone, gone, only for so long, though I left with grace and style.” But upon closer inspection, the nuanced narrative seems to originate from a ghostly presence. Equal parts earthy and ethereal, the baritone notes on the break are spectral and majestic. The song closes as stacked acoustic riffs intertwine with lanky pedal steel.

Even in their earliest days, The Long Ryders dotted their albums with socially conscious songs. That tradition continues here with three tracks. On “To The Manor Born,” muscular guitars collide a wash of keys, throbbing bass and a Rattlesnake shake backbeat. The melody and arrangement, a potent combo-platter of Country twang, Yacht Rock elan and ‘70s AOR boogie. Perspicacious lyrics take a decadent dilettante to task; “Heavy-handed, hedonistic, got your lover and your mystic, yeah, speed of sound with a sonic boom, the loudest voice in every room, Darling, what are you going to do/Are you gonna go searching in the middle of the night, with a dashboard savior and a socialite, you can’t fake that image, all ripped and torn, ain’t so hard to know you’ll always be to the manor born.” Guitars rip, shred and synchronize on the break before reviving the shout-it-out chorus and quietly winding down.

“Song For Ukraine” arrives halfway through the record, the instrumental acts as a musical sorbet, a palate-cleanser between courses. Weepy violin crests atop liquid acoustic arpeggios, barely-there vibes and a bit of back-porch banjo. Shot through with empathy and elegance, the listener can’t help but sideline petty personal thoughts and contemplate the strength and sacrifice the indefatigable Ukrainian people have displayed this last year.

Meanwhile, “Elmer Gantry Is Alive And Well” is a rollicking stomp that juxtaposes cantankerous guitars, plinky piano, thready bass lines and a thunderous backbeat. Of course, The Long Ryders take a page from Elmer Gantry, a 1920s novel from Sinclair Lewis that exposed the hypocrisy of organized religion. Building off that blueprint, lyrics deftly excoriate the country’s current political divide, laying the blame at the clown-size feet of the twice-impeached ex-Cheeto-in-chief; “You know you’re going to lose the crown when you hold the bible upside down, from sea to shining sea, hypocritical conspiracies, the 21st century has gone to hell, Elmer Gantry is alive and well.” Stinging guitar riffs on the break fly as fast and furious, as the sharp rejoinders that take aim at gullible followers; “By the fire, you’ll be baptized, yes, the coup will be televised, the rocket’s red glare has made you blind, I’m just looking for some peace of mind/They’re going to run you out of town, then your statues gonna hit the ground, the only people that see you won are hucksters, grifters and charlatans.” An extended break rounds the final hairpin turn, briefly powering down before roaring back to life, finally collapsing in a feedback-tastic heap.

A couple of tracks, “That’s What They Say About Love” and “Country Blues (Kitchen)” add some new colors to the Ryders sonic palette. The former shares some musical DNA with a Who deep cut, “Dreaming From The Waist,” but the arrangement and instrumentation lean closer to the Gypsy Jazz of Quintette du Hot Club de France. Grappelli-esque violin wraps around buoyant upright bass, Django-fied guitar and a trap-kit beat. With tongue planted firmly in cheek, Sid adopts a Al Jolson-ish croon as he optimistically extols the virtues of love; “As sure as you’re born, you’re gonna be warned, how this big day is coming, it’s quite au fait, that’s what they say about love.” At one point, he brightly exclaims; “loneliness, hey, that’s over, I tossed the bad times right over my shoulder.” Ultimately, this Gallic charmer is hard to resist.

The same can be said for the latter. A Bluesy shuffle, the song features bottleneck slide guitar, smoky harmonica, slap-back bass lines, barrelhouse piano and a see-saw beat. Something of a shaggy dog saga, it involves riding the rails, a prevaricating cousin and a confidence scheme gone horribly awry; “Tell the porter, the engineer, my destination is anywhere but here, how did I fall between the cracks, seems my nerve just jumped the tracks, my cousin Henry, he went bad, took all the money that I had, so I caught the first train, I hopped the freight, down to Mississippi, please don’t hesitate/So let it roll, down to Jackson, let it roll, you’ve got to leave it in the kitchen mama, that Country Blues got your soul.”

While it’s tempting to view certain songs through the prism Tom Stevens’ absence, the album’s final three tracks are explicit homages to The Long Ryders’ fallen brother. The most poignant in this aural triptych is “Tom Tom.” Filigreed acoustic fretwork, fluttery mandolin, quicksilver mandolin, and a bit of high lonesome-harmonica envelope feathery harmonies and a wistful melody. Melancholy, but never maudlin, lyrics like “Tom Tom, always right in tune, he’s grooving on the left side of the engine room, jammin’ in a dream from 40 years ago, I need to play along, and I want you all to know, keep the love but lose the sorrow, and let it fly into tomorrow,” allow us all a measure of catharsis.

Plucky guitars fuel the lithe and deceptively sunny “Until God Takes Me Away.” Ostensibly a sprightly ode to love, the final verse could also serve as a graceful encomium to the self-effacing Hoosier who anchored The Long Ryders’ low-end through thick and thin; “I have to state it once before I go, it wouldn’t do to live and not let you know, as our lives are shared in this display, let me sing to you without delay, you have love until God takes me away.”

Finally, to paraphrase James Brown, The Long Ryders’ “give the bassist some.” The closing number “Flying Out Of London In The Rain” was written and recorded by Tom Stevens, with some sweet backing vocals from his daughter, Sarah. While the other band members add some instrumental color, lyrics offer a sly victory lap, following the triumph of Psychedelic Country Soul; “The crowds they bring a smile, recognition in the street, promoter man wants to do another tour, and the world is at your feet.” It’s a bittersweet end to a beautiful record.

Along with Sid, Stephen and Greg, special guests included Murray Hammond (Old ‘97s) on bass, Kerenza Peacock on violin, Charles Arthur on piano, Ben Moore on organ and DJ Bonebrake (X) on vibes. Once again, Ed Stasium handled production chores.

September November is by turns, sharp, reflective, sly, tender, smartass and joyful. In fact, it’s pretty close to perfect. Somewhere, Tom Stevens is smiling. (book of ecclisiastes/Tom’s Smiling)