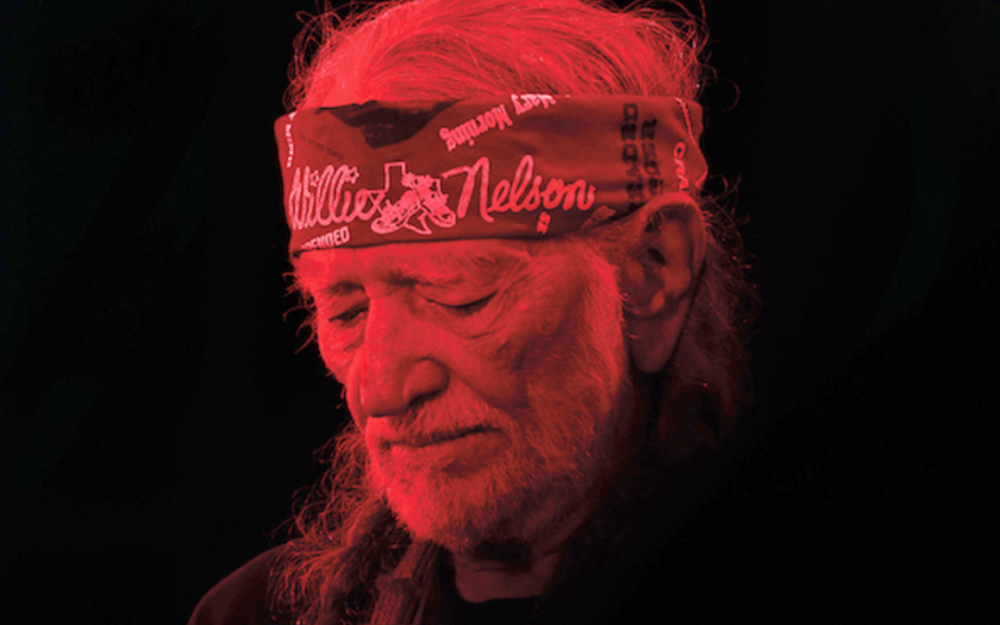

BY ELENI P. AUSTIN

“I woke up still not dead again today, the news said I was gone to my dismay/Don’t bury me, I’ve got a show to play, and I woke up still not dead again today.”

That’s Willie Nelson, happy to spend another day above ground on “Still Not Dead,” a new song on his 72nd (!) studio album, God’s Problem Child.

No two ways about it, Willie Nelson is a fucking force of nature. He was born in Abbott, Texas in April 1933, the height of the Great Depression. Raised by his grandparents, he exhibited an affinity for music early on. He wrote first song at age seven, by 10, he was fronting his own band.

Following a stint in the Air Force, Willie worked as a disc jockey, bouncing from Fort Worth to Portland, Oregon and Vancouver, Washington before returning to the Lone Star State. He was a disc jockey by day and a working musician at night, but initially, he gained recognition as a songwriter. He sold his first couple of songs, “Family Bible” and “Night Life” to a local musician for a combined total of $200.00

Relocating to Nashville in 1960, he signed a deal with a publisher and pretty soon, established artists like Faron Young, Patsy Cline and Roy Orbison scored number one hits with “Hello Walls,” “Crazy” and “Pretty Paper.” But Willie wanted to record and perform his own music. His debut album was released in 1962 and was soundly ignored by the Nashville establishment, and the world at large.

He continued to earn his keep as a songwriter, and it was around this time that he fell in with like-minded songwriter-musicians like Kris Kristofferson, Dottie West and Waylon Jennings. Throughout the ‘60s, Music City was wall-to-wall big hair, sequins and rhinestones. Willie and his pals eschewed the glitter and glamour, opting for jeans and increasingly longer hair. The Nashville establishment viewed them as outlaws and outliers.

Songwriting royalties had made Willie financially solvent, but artistic success still eluded him. After his Ridgetop, Tennessee ranch burned to the ground and his second marriage ended in acrimony, Willie returned to Texas, specifically, Austin, in 1975. A college town, Austin is something of a liberal enclave;, Willie grew his hair even longer and let his freak-flag fly.

He soon began hosting an annual 4th Of July concert/picnic that allowed rednecks and hippies to peacefully co-exist. Coming home allowed Willie to find his footing, artistically and commercially. Groundbreaking albums like Shotgun Willie, Phases And Stages and Redheaded Stranger became bona fide hits. Soon this self-proclaimed outlaw was performing on “Saturday Night Live” and being invited to the White House, (where an “insider” invited him on to the roof and he promptly blazed a joint!)

In 1978, Willie released Stardust” an album of Jazz and Pop standards that fully introduced him to the mainstream. Songs like “Moonlight In Vermont,” “All Of Me” and “Blue Skies” featured his unique phrasing and gritty guitar work. His version of “Georgia On My Mind” earned him a Grammy for Best Male Country Vocal.

Soon Hollywood came calling; Willie appeared in movies like “Electric Horseman” and starred in “Honeysuckle Rose,” the latter a thinly veiled version of his own life. In the ‘80s he recorded albums at a furious clip, and toured non-stop, both as a solo artist and as part of the Highwaymen, a Country super group featuring Willie, Johnny Cash, Waylon Jennings and Kris Kristofferson.

But in 1990 the Internal Revenue Service seized his assets claiming he owed the government 16 million dollars. It turned out his accountants hadn’t paid his taxes for years. To satisfy the debt, Willie released The I.R.S. Tapes: Who’ll Buy My Memories, a two CD set of bare-bones recordings featuring Willie and his guitar, Trigger. Despite the thrown together, odds-n-sods quality of the album, it went on to pay down 3.6 million dollars of his debt. Selling off what was left of his assets, (to fans who promptly returned his keepsakes), and touring extensively put him back in the black.

By the 21st century Willie had kinda-sorta settled down with his fourth wife, Annie. He split his time between touring, recording and raising their kids, Lukas and Micah in Maui, Hawaii. (All told, he has fathered seven children). An environmental activist and cannabis enthusiast, Willie’s tour bus runs on bio-diesel fuel, (made of vegetable/soy bean oil), created by a company he and Annie own. A longtime supporter of LGBT issues, he recorded a version of Ned Sublette’s song, “Cowboys Are Frequently Secretly Fond Of Each Other.”

Despite indulging in a lifestyle fueled by wine, women, weed and song, Willie has, sadly, outlasted many of his contemporaries and running buddies. In the last several years he has said goodbye to Waylon Jennings, Johnny Cash and most recently, Leon Russell and Merle Haggard. But Willie keeps plugging away. Through the years his albums have run the gamut from brilliant to workman-like to abysmal. His latest, God’s Problem Child, is actually pretty great.

The album gets off to a rollicking start with “Little House On The Hill.” An irresistible hybrid of Gospel and Western Swing, the tune is powered by a shuffle rhythm, prickly electric guitar, twangy Trigger riffs and tart harmonica runs. The titular house feels Willie’s version of Superman’s Fortress Of Solitude; “That little house has weathered many storms, it’s a place that feels so cozy and so warm/It’s waiting there for me and it’s where I long to be, I’m going back to that little house on the hill.”

Willie and longtime producer Buddy Cannon have co-written the lion’s share of the songs here. Matters of the heart get the once over twice on both “True Love” and “Your Memory Has A Mind Of Its Own.” The former is a burnished ballad propelled by plangent pedal steel and quavery harmonica. Despite consistent heartache, disappointment and diminished returns, he hasn’t given up on romance; “You taught me how to twist and turn and bend before I break, and fake it till I make it all for true love’s sake/You’re worth all the heartaches and I’d do it all again, I’ll leave this world believing true love you’re still my friend.”

Willie and longtime producer Buddy Cannon have co-written the lion’s share of the songs here. Matters of the heart get the once over twice on both “True Love” and “Your Memory Has A Mind Of Its Own.” The former is a burnished ballad propelled by plangent pedal steel and quavery harmonica. Despite consistent heartache, disappointment and diminished returns, he hasn’t given up on romance; “You taught me how to twist and turn and bend before I break, and fake it till I make it all for true love’s sake/You’re worth all the heartaches and I’d do it all again, I’ll leave this world believing true love you’re still my friend.”

The latter is a Honky-Tonk lament in ¾ time. High lonesome harmonica intertwines with courtly Spanish arpeggios from Trigger. Here Willie tries to anesthetize his heartache; “I can smoke and I can drink until it’s out of view,” but like a phantom limb, the pain never retreats, and he learns to live with it.

Willie’s sardonic, self-deprecating humor is on full display on three tracks. The aforementioned “Still Not Dead” is a twangy two-step that drafts off that infamous quote, “rumors of my demise have been greatly exaggerated.” Wheezy harmonica, barrelhouse piano and crackling guitar crests over a locomotive rhythm and boinging jew’s harp. Addressing internet hearsay and morbid innuendo, he wryly assures the listener; “I woke up still not dead again today, the gardener did not find me that way/You can’t believe a word that people say, and I woke up still not dead again today.”

“It Gets Easier” offers a good-natured road map for navigating old age. Supple pedal steel lattices over raspy harmonica, coruscated Wurlitzer colors and Trigger’s patented rough-hewn riffs. Willie notes longevity has its privileges, as social hypocrisy falls by the wayside. “It gets easier to tell the world to wait, and it gets easier to watch the world fly by and tell it I’ll catch up, but not today/ I don’t have to do one damn thing that I don’t want to do, except missing you, and that won’t go away.”

On the chugging “Delete And Fast Forward” Willie shares his dismay over the recent Presidential election. This gritty rocker is anchored by skittery electric riffs, prickly power chords and sweet n’ sour harmonica. The lyrics offer some helpful coping mechanisms for these trying times; “delete and fast forward my friend, the elections are over and nobody won/You think it’s all over but it’s just settin’ in, delete and fast forward again.”

Even the songs Willie didn’t have a hand in writing feel tailor made to suit his strengths. “Old Timer” is a wistful piano ballad that takes inventory of a life well-spent. Here he quietly notes “you’ve been down every highway, burned your share of bridges, you found forgiveness/You think you’re that young bull-rider till you look in the mirror and see an old timer.”

“A Woman’s Love” is a south of the border charmer that displays a perspicacious view of women that almost makes up for his odious early ‘80s hit, “You Were Always On My Mind.” Meanwhile the slow-as-molasses melody of “Butterfly” underscores a tender acknowledgement of a woman’s tensile strength. The tune ends with simply gorgeous Flamenco flavored filigrees courtesy Trigger.

The title track is the album’s centerpiece, it was co-written by Outlaw acolyte Jamey Johnson and legendary singer-songwriter Tony Joe White. Swampy and Bluesy in all the right ways, the song shares some musical DNA with B.B. King’s minor key masterpiece, “The Thrill Is Gone.” Willie alternates verses with Jamey and Tony and Leon Russell (in one of his final performances). His weathered Oklahoma drawl adds a measure of gravitas to this defiant tale.

The instrumentation includes sultry harp, a wash of Hammond B3 tinkling percussion and roiling bass, but it’s Willie’s dexterous extended solos on Trigger that command the most attention.

Other interesting tracks include the loping shuffle of “Lady Luck,” the melody feels like a cosmic cousin to “My Heroes Have Always Been Cowboys.” “I Made A Mistake” weds a gilded see-saw arrangement to a sad-sack waltz. Before things become too self-pitying, (once again) Trigger rides to the rescue.

The album closes with “He Won’t Ever Be Gone,” a tender encomium to his old compadre, Merle Haggard. A soulful recollection of their fraternal friendship, it name-checks several of the Bakersfield native’s most iconic songs, noting “(he) left us a lifetime of song and he won’t ever be gone, we’ll be singing him back home from now on.” Never maudlin or melodramatic, the tribute includes barbed electric guitar riff-age from Merle’s son, Ben. It’s a bittersweet finish to an assured collection of songs.

Willie Nelson has always broken rules, flouted convention and kicked against the pricks. He’s written classic songs and put his own distinctive spin on Pop favorites and Jazz standards. Love it or hate it, his behind the beat phrasing remains non pareil. Equally compelling is the dusty interplay between Willie’s trusty stead Trigger and (longtime band member), Mickey Raphael’s harmonica. The combination is equal parts honey and woodsmoke, adding a rustic patina to each song.

There aren’t many octogenarians that debut at #1 on the Country charts and #10 on the Billboard Top 200. God’s Problem Child accomplished both feats without breaking a sweat. Simply put, Willie’s music never gets old.