By Heidi Simmons

—–

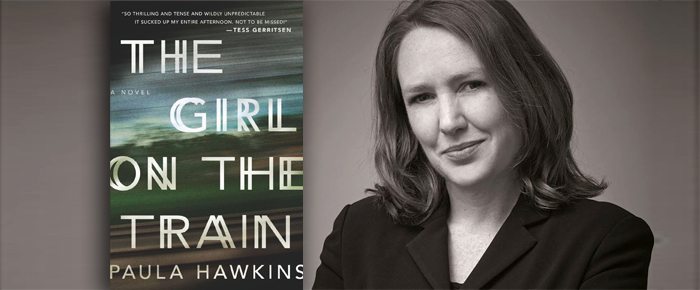

The Girl on the Train

By Paula Hawkins

Fiction

—–

Sadly, violence against women plagues this planet. In Paula Hawkin’s The Girl on the Train (Riverhead Books, 336 pages), homicide, infanticide and rape make this tale more about examining victims than exploring a mystery.

The story begins with Rachael on her daily train commute to London. The back and forth trip is the highlight of her day. She enjoys looking out from the train to get a glimpse of the lives of others. She routinely sees the same people in their yards or in the windows of their homes as she passes.

One of the houses she watches from the train is that of Tom, her ex-husband and Anna, his new wife. They have a baby, Evie. Rachael can see the pink curtains in the baby’s room that was the guest room when she lived there.

Tom had an affair with Anna that resulted in pregnancy. When they divorced, Tom kept the house, paying Rachael a small settlement. Now, when she passes the home that was once hers, she feels the sharp pain of lost love and betrayal.

Rachael has a serious, serious, drinking problem. She blacks out. And when she drinks, people must fill in the blanks. She’s ashamed and humiliated by her bizarre behavior. She calls her ex-husband at all hours, stops by his house and harasses Anna and the baby. Further more, Rachael’s obnoxious, overweight, self-loathing and doesn’t understand boundaries.

As a voyeur, Rachael fantasizes about another couple just a few houses down from her former home. Seems every time she passes, they are outside enjoying each other and their garden; in the mornings the couple drink coffee together and in the evenings they sip wine. It’s the perfect romantic life she always wanted with Tom.

One day, Rachael briefly observes someone else in the yard of her “ideal couple’s” home. It’s a different man in an intimate embrace. A few days later, the couple is in the news and she learns their real names are Megan and Scott. Megan has gone missing and is eventually found. Dead.

Coincidently, Rachael was in the neighborhood on a drunken rampage at the time of Megan’s disappearance. Haunted by bad dreams and with a nagging sense she knows something important, Rachael interjects herself into the investigation. Not only does she go to the police, but also goes to see Scott, the handsome, grieving husband.

This complicates things for Rachael, Scott and basically everyone else in her life, including Tom and Anna.

Rachael’s a mess and sobriety is unlikely, if not impossible. But as she considers the events of the night Megan went missing, she realizes she must know who the killer is and her road to redemption is solving the crime.

The Girl on the Train is told by the first person accounts of the women in the story. Rachael, Megan and Anna. Rachael dominates the narrative. Each woman tells her perspective which starts with a date and time of day. They are not journal entries, but rather a chronology that overlaps and gives the reader a bigger picture of unfolding events and developing suspense.

All three women have something in common. Each is dealing with the psychological implications of motherhood. Rachael believes her downward spiral is due to her inability to conceive. This results in her feeling inadequate and generates low self-worth.

Megan was abandoned by her lover after her baby died in an accident.

And Anna got knocked-up by the man she was having an affair with and found herself unprepared for being a parent.

Rachael, Megan and Anna are pathetic and tragic characters. Instead of overcoming their misfortune, they wallow in it. Worse, the men in their lives victimize them. Not a single female character in this book has a healthy relationship with a man.

The men are abusers and rapists. One is a killer.

As readers, we are starved for well-written, page-turning mysteries. Gillian Flynn’s novel, Gone Girl, was a terrific suspense thriller with a fresh and surprising twist. The construction of the narrative was equally clever and engaging. Flynn uses the journal entries as chapters, which correspond to the date of the girl’s disappearance.

It’s easy to compare the two novels and no doubt the publisher took advantage of the similarities. And there are a few: “Girl” in the title, dated chapters and a missing woman. But The Girl on the Train doesn’t come close to the suspense of Gone Girl. The characters’ dated entries are just a way to have multiple first person voices to tell the story and nothing more.

Rachael’s drinking becomes tedious. The psychological torment and domestic abuse is painful and dreary. The pathology of the women is one-dimensional. The suspense is minimal and the outcome is disappointing.

Author Hawkins’ writing is smooth and easy. Her characters act and talk like real people. I just didn’t like or care about them. But for many women, The Girl on the Train shows how easy it is to get derailed by men.