By Eleni P. Austin

“Is she really going out with him? Is she really going to take him home tonight/Is she really going out with him, ‘cause if my eyes don’t deceive me, there’s something going wrong around here.”

Forty years ago, that song announced the arrival of Joe Jackson with a measure of snarl, sincerity and incredulity. Punk Rock hadn’t managed to invade Top 40, but New Wave (a shinier, happier alternative) had begun making some inroads with artists like Blondie, the Police and Joe leading the pack.

David Ian Jackson was born Burton upon Trent Staffordshire, England in 1954. A musical kid, he played violin by age 11, before persuading his parents to buy a piano. He was writing his own music by the time he was a teen and received a scholarship to London’s Royal Academy of Music. After studying musical composition for three years, he graduated and began playing in a band.

Initially known as Edward Bear, the band morphed into Edwin Bear and finally, Arms And Legs. It was around this time that he earned a nickname that stuck, thanks to his passing-resemblance to the puppet character, Joe Piano. Pretty soon though, he struck out on his own, recording a set of demos that got him signed to the A&M label.

His debut, Look Sharp, arrived in April 1979 and featured a crackling collection of songs that displayed his caustic wit, sparkling musicianship and barbed songcraft. It quickly earned comparisons to antecedents like Graham Parker and Elvis Costello, and all three labelled the “Angry Young Men” of Punk. Look Sharp did surprisingly well in America, hitting the Top 20. Less than six months later Joe released a follow-up, I’m The Man, which felt as sagacious and succinct as his debut.

From then on it seemed like Joe Jackson made it his mission to demonstrate a musical dexterity and sophistication that eluded his peers, (save, maybe Elvis Costello). 1980’s Beat Crazy, credited to the Joe Jackson Band, deftly explored Reggae and Ska. A year later Jumpin’ Jive displayed an affinity for ‘40s and ‘50s Jump Blues and Big Band hits best exemplified by Louis Jordan and Cab Calloway. Way ahead of its time, it pre-dated the (wildly irritating) Neo-Swing craze of the late ‘90s by nearly 20 years.

Joe hit pay dirt with his fifth effort, 1982’s Night & Day. The album was inspired by his recent move to New York City and the music reflected the city’s melting pot culture. Here, he successfully tackled Latin-Jazz, Soulful ballads, stylish and sardonic Pop songs. It was a bona fide hit, reaching #5 on both sides of the Pond. It also earned him two Grammy nominations. Rather than take a victory lap, he dove head first into scoring his first film, an obscure Debra Winger thriller entitled “Mike’s Murder.” It netted him another Grammy nomination, this time for Best Pop Instrumental.

His next record, 1984’s Body and Soul was a deeper dive into Jazz, (even the cover emulated Sonny Rollins “Vol. 2” album). It featured a couple of minor hits, “You Can’t Get What You Want (Till You Know What You Want)” and “Be My Number Two.” (Less scatological then you’d think). Exhausted from relentless touring, he took a couple of years off and returned with Big World, a three-sided live record featuring brand new music but no applause. Joe insisted the audiences remain mute.

For the next several years it felt like he did his best to subvert his commercial instincts. There was another soundtrack score, this time for Francis Ford Coppola’s flop, “Tucker.” 1987’s Will Power was designed to show off his serious composer chops, no one cared. Blaze Of Glory and Laughter & Lust released in 1989 and 1991, respectively, showed glimmers of hope, but the rest of the ‘90s was a particularly fallow period. The decade was dotted with myriad greatest hits compilations and detours into Classical territory, the self-indulgent “song cycle” of 1994’s Night Music and 1997’s Heaven & Hell. 1999’s Symphony No. 1 was a mix of Classical and Jazz compositions that featured players like Terrance Blanchard and Steve Vai and earned Joe another Best Pop Instrumental Grammy nomination. Finally, as the 21st century dawned it seemed like he was ready to return to Rock N’ Roll.

Baby steps were taken on albums like Summer In The City: Live In New York and Night and Day II, but his his homecoming felt complete with Volume 4. The 2003 effort was credited to the Joe Jackson Band and was meant to pick up where Beat Crazy left off. It was his best received album in decades.

Four years later, his Rain record mined similar territory. He took a brief, Jazzy detour with Duke, which served as a tribute to Jazz icon Duke Ellington. Then in 2015 he released Fast Forward; a collection of four Eps arranged as a full-length album, each part recorded in a different city; New York, New Orleans, Amsterdam and (what had become his new hometown) Berlin.

Now Joe is back with his 20th studio album, pithily entitled Fool. It opens with the one-two punch of “Big Black Cloud” and “Fabulously Absolute.” Drums hammer in the distance as Joe pounds out portentous piano notes and guitars shiver on “….Cloud.” Dark and defiant, weather is a metaphor that signals tough times ahead. The characters here feel enveloped by suburban ennui; “No money, no sex, no fun, get on the treadmill and run, run, run.” The instrumentation ebbs and flows, cacophonous one minute, decorous the next. It functions as something of an overture to the record.

“Fabulously…” flips that script, discarding ornate instrumentation in favor of a stripped-down, built for speed sound. Muscular guitar and tensile bass collide with descending piano runs and a thwoky backbeat. Sophisto Joe retreats and a Brexit version of Joe The Plumber takes his place, railing at elitists who think they have the proletariat all figured out; “Go on and shove it in my face, how I should join the human race, or maybe whisper in my ear, whatever I should want to hear/Like I’m a fascist or a fool, who didn’t go to snooty school, I get it wrong on the remote, and even wronger when I vote.” His sarcasm is implicit in his sneer as he notes, “You’re so fabulously absolute…”. Woozy and whirring Moog notes (which would seem more at home on a Styx song), cut through the fractious fun.

The eight tracks here are evenly split between eloquent Jazz/Pop and economical Power Pop/Punk. The sing-songy “Dave,” has a Musical Hall quality that feels quintessentially British. Like Ray Davies of the Kinks, along with Difford & Tilbrook from Squeeze, Joe excels at painting vivid portraits of everyday life. Here, he ups the ante by framing Dave’s tale in a lovely, Country-tinged melody. Jangly guitars dovetail with angular bass, chiming piano and a stumbling stair-step rhythm.

Dave eschews a frenetic, 21st century lifestyle watching the waves, meanwhile the song’s narrator bemoans his own fast-paced lifestyle; “…You and me just keep on rushing ‘round the world to chase the perfect crime/Could It be that while we’re rushing ‘round the world, we’re wasting all our time?” This epiphany is buttressed soaring guitar and twinkling piano.

“32 Kisses” is equal parts plaintive and propulsive. Melancholy piano intertwines with sinewy guitar, roiling bass lines and a tick-tock beat. Joe wistfully recalls a former love who has clearly moved on to bigger and better things; “I saw you grow, I saw it all, from the head of your class to the queen of the stage/Strange I know, What I recall is the 32 kisses at the edge of the stage.” Suddenly, the song downshifts into a sad-sack waltz, laced with honeyed guitar.

Finally, “Strange Land” is a pensive piano ballad that matches downcast chords to cogent lyrics of self-reflection. Joe doesn’t equivocate, as he questions his place in the world; “Thought there was a right turn here, turns out to be wrong, thought there was a short cut there, seems to be so long/I study the lines on the map and the lines on my face, am I out of time or out of place?” Rippling piano notes on the break are bleak and beautiful and slightly heartbreaking. The gravitas of this cut mirrors Elvis Costello’s “Man Out Of Time” and Sting’s “Soul Cages.”

Happily, not every track here sacrifices id for superego. “Friend Better” is sleek and playful, a rollicking R&B tune that is anchored by a kick-drum beat and accented by chunky piano notes, prickly bass and wily guitar. The lyrics offer an oblique toast to friendship couched in some sage advice; “If you were to use your head, then you would-Just forget her/Listen what the wise man said: Lover Good-friend better.”

The title track is the album’s centerpiece, blending Greek, Celtic and Middle Eastern influences, underscored by whirling dervish guitar, bee-stung bass and off-kilter percussion. Just as quickly the whole thing pivots on a dime, slipping into a lithe Samba groove. Guitar and piano lock into a nimble pas de deux as Joe indulges his inner Tito Puente. All the while the lyrics drill down on the cultural necessity of fools and jesters.

The album closes on an ambitious note. “Alchemy” floats out of the speakers like a louche, lush, long-lost collaboration between Burt Bacharach and Michel Legrand (R.I.P.) Powered by a martial cadence and a plucky string arrangement, it features fluttery flute accents that would make Ron Burgundy blush. Veiled lyrics hint at greatness; “Thrill-to secrets never told, Taste-the bitter turned to sweet, See-the dross turned to gold, Hear-a B sharp turned to C.” But the rewards are elusive. Still, his adept piano coda exhales like a post-coital cigarette.

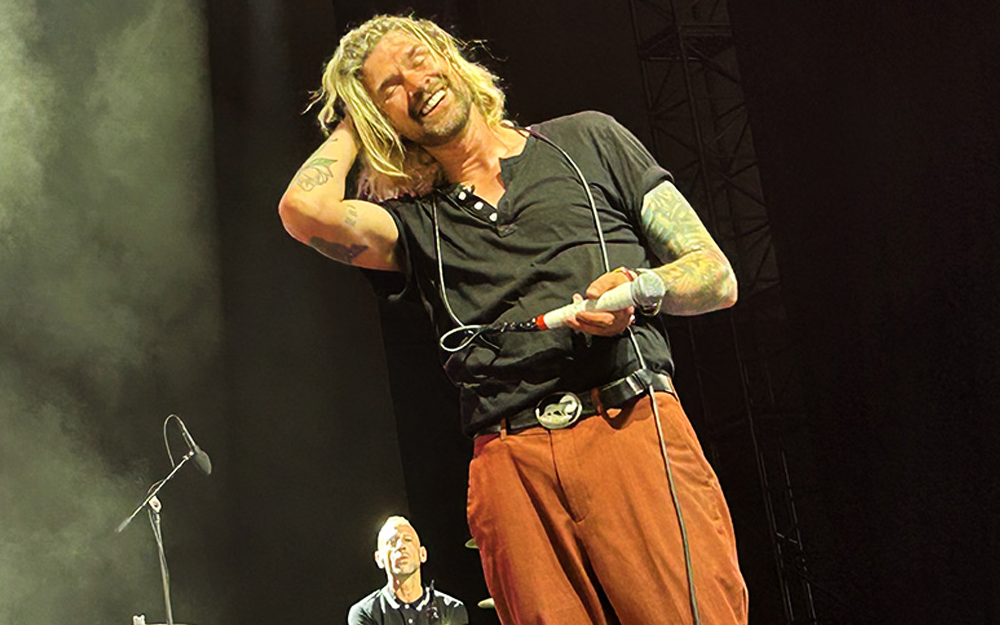

Joe’s last world tour ended in Idaho, and that’s where this record was created, in Boise’s Tonic Room studio. It features his longtime backing band, guitarist Teddy Kumpel, drummer David Yowell and bassist Graham Maby who has been with Joe since his very first album.

Joe Jackson has never courted public opinion, instead he has simply followed his muse. Fool continues that tradition, with no regrets.